Today’s post is Part 3 in the THB series Weather Attribution Alchemy. The previous installments are:

Hurricanes are the poster child of climate politics. As you can see in the actual poster above, a popular narrative exists that hurricanes are caused by carbon dioxide emissions from power plants (or makes them more frequent, more intense, more wet, more slow, more fast). Like the movie poster above, in which the hurricane is spinning the wrong way, evidence and research has not always conformed to the narrative.

A pseudo-scientific cottage industry has sprung up that associates just about every notable hurricane with climate change. Today, I take a look at recent efforts to attribute hurricanes to greenhouse gas emissions.

The impacts of climate change on hurricanes are claimed to be huge. Here are some examples from 2024:

Hurricane Milton was 40% more likely.

Hurricane Helene was more than 100% more likely.

Typhoon Shanshan was 36% more likely.

Typhoon Gaemi was about 50% more likely.

Hurricane Beryl was almost 100% more likely.

Press releases making such incredible claims flood the zone after every major storm and are uncritically repeated by the major media around the world.

Let’s take a closer look at what lies behind these press releases. Like the hurricane spinning the wrong way in Al Gore’s movie poster, the attribution tricks sit out in plain sight, visible to anyone willing to have a look.

First Trick — Attribution Inflation

Earlier this month, Tropical Cyclone Chido made landfall in Mayotte, part of the archipelago between Madagascar and the African continent, before going inland across Mozambique. Chido was a small but powerful tropical cyclone and resulted in the deaths of almost 100 people.

In the days after the storm the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London issued a press release claiming:1

The IRIS model estimates that climate change uplifted the intensity of a tropical cyclone like “Chido" from a Category 3 to Category 4. A “Chido” type storm is about +40% more likely in the 2024 climate compared to a pre-industrial baseline.

Wow, 40% — that is a big number! It is about an order of magnitude larger than the most extreme projections of the IPCC AR6 for changes in tropical cyclone intensity by 2100.

It turns out that 40% is actually less than 3%.

Here is the trick: The Imperial College press release claims that a storm like Chido has changed from a 1 in 13.9 year event to a 1 in 10.1 year event — In other words, from an event with a 7.2% chance of occurring in any year to an event with a ~10% chance of occurring.

Taking the claim at face value that means that a storm like Cyclone Chido is 2.8% more likely (i.e., 10% minus 7.2%). That wouldn’t sound too scary.

But if we round the return periods to 14 and 10 years respectively, and take the percentage change of the percentage change (10% divided by 7.14%) — Voila — We get a 40% change.

In a different context, the New York Times explains that “percentage change values may give a misleading impression of what is really happening.” Indeed.

We are already seeing the effects of climate change today in floods, fires, and storms. And the temperature keeps rising. By the end of the century, up to a quarter of the world is likely to be uninhabitable. —Grantham Foundation 2024

Second Trick — Begging the Question

The Imperial College approach to attribution assumes the conclusion that it seeks to prove. They do this by simply assuming that every storm is made stronger due to warmer oceans, which indeed have warmed due to increasing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

With this starting point it is straightforward to conclude that the storm that just happened was made more likely due to climate change. Imperial College explains:

The difference in the storm intensity and likelihood of this storm intensity between the counterfactual climate and today’s climate can be attributed to climate change.

Simple, right?

For instance, they provide an example of their method applied to Typhoon Haiyan (2013, Philippines) which :

According to IRIS, in a cooler climate without human-caused warming, typhoons as powerful as Haiyan are expected to hit the Philippines about once every 9,300 years, but in the climate with 0.8°C of warming, similar typhoons are expected to occur about once every 130 years.

Wow! Using the percentage of a percentage trick to characterize increased likelihood, that means that a storm like Haiyan was 7,000% more likely due to climate change.2

The problem with assuming a direct relationship between sea surface temperatures and hurricane likelihoods and return periods is that tropical cyclones are influenced by many environmental factors beyond just ocean temperatures.

The underlying theory of hurricane intensity was developed by Kerry Emanuel, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in the 1980s to describe what he called the maximum potential intensity of tropical cyclones.

Emanuel also recognized that “hardly any storms” reach their maximum potential intensity, and fail to:

. . . maintain intensities near their maximum intensity for any appreciable period, even when potential intensity remains high. This points to flaws in the notion, arising from idealized model studies, that tropical cyclones can maintain nearly steady states and shows that most storms eventually encounter adverse environmental influences, such as vertical wind shear or storm-induced ocean surface cooling, even when they remain over warm ocean water.

Such complexities mean that simple storyline attribution — warmer oceans predictably mean stronger storms — is inappropriate when used to characterize the behavior of individual storms.

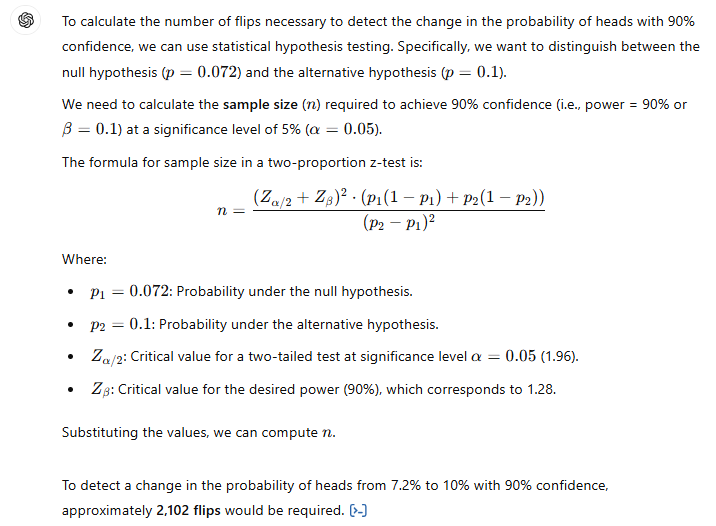

But let’s go with the results of the Imperial College conclusions of an annual chance of a Chido-like storm increasing from 7.2% to ~10%. How many years would it take to detect such a change in observations, using the IPCC threshold for achieving detection (90% confidence)?

According to ChatGPT, as you can see in a coin flip example below, more than 2,100 years.3

Even if storms like Chido were now 2.8% more likely, it would take a very, very long time to detect such a change. Perhaps that is why assumptions are favored over evidence.

Third Trick — Ignoring Evidence

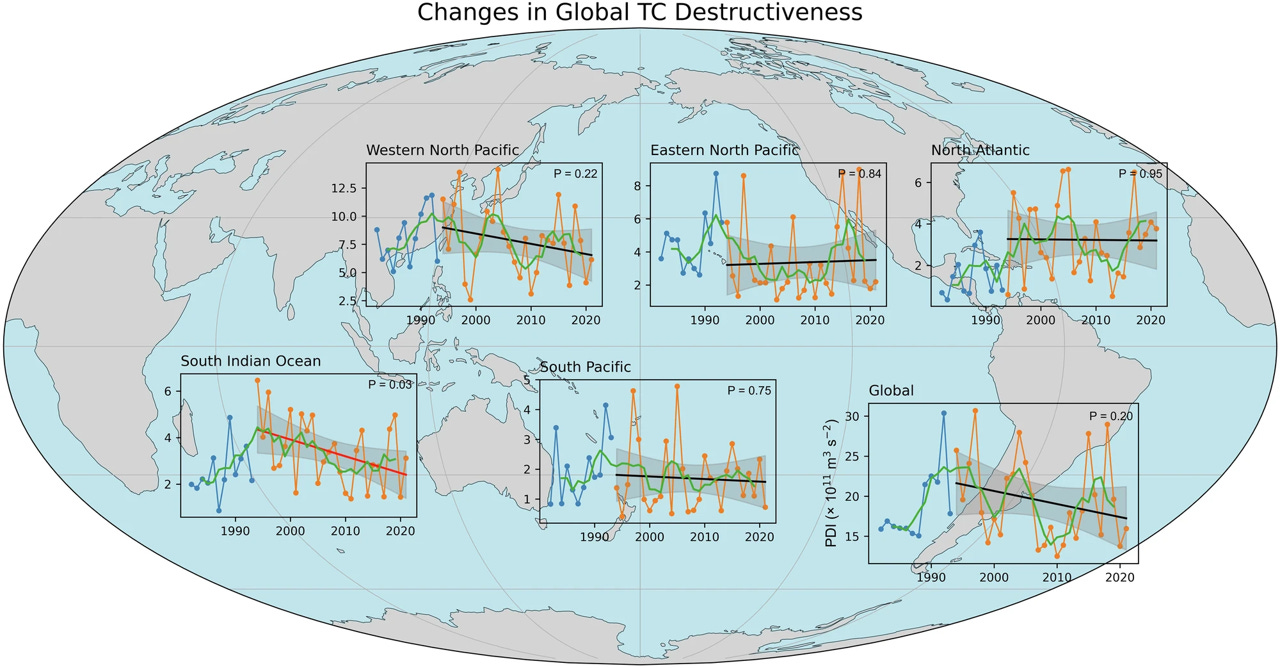

The figure above comes from a recent paper (Tu et al. 2024) titled — Decreasing trend in destructive potential of tropical cyclones in the South Indian Ocean since the mid-1990s. In fact, as you can see in the figure, in no ocean basin have tropical cyclones seen an increase in their destructive potential over the past 30 years.4

Tu et al. explain (emphasis added):

Here we investigated changes in the destructiveness of tropical cyclones worldwide using the power dissipation index and found that there is no clear trend in most basins, but a significant decrease in power dissipation index has been detected in the South Indian Ocean basin since 1994, which is almost entirely due to a decrease in both tropical cyclone frequency and duration in this basin.

The South Indian Ocean is the basin where Cyclone Chido made landfall earlier this month.

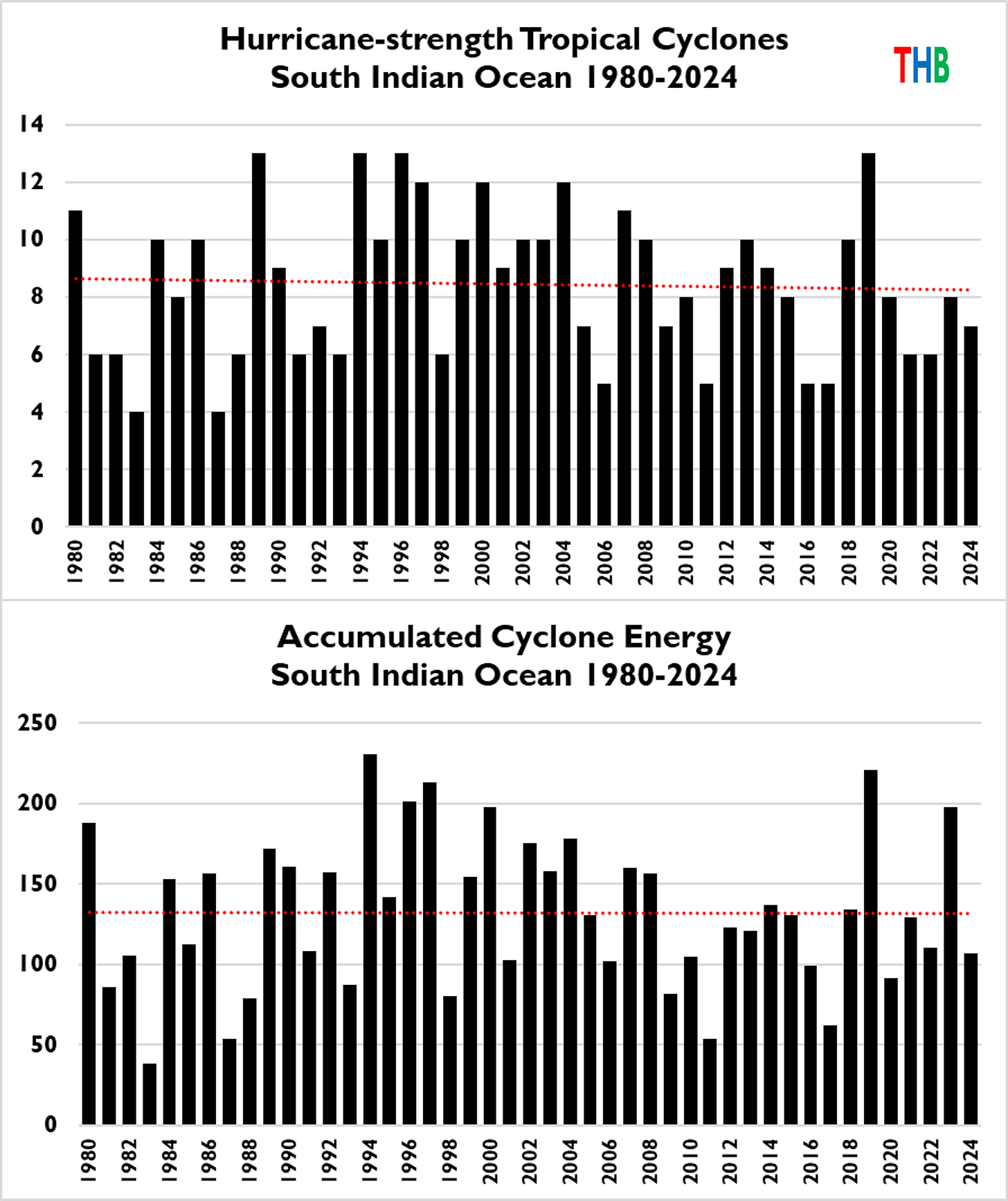

The figures below shows (top) the frequency of hurricane-strength tropical cyclones in the South Indian Ocean along with (bottom) accumulated cyclone energy (ACE), which integrates frequency and intensity — Neither shows a trend over 1980 to 2024.

Claims that certain events have increased in their likelihood of occurring should always be accompanied by a time series of those events to demonstrate that increase — increases such as 7,000% or even 40% over 40 years should be obvious, even without statistics.

What is Going on Here?

Extreme event attribution is puzzling.

The most charitable explanation for the proliferation of dodgy attribution claims is that there is a demand for them, including by many in the media and on the climate beat. That demand will be filled by someone — even if the “science” is more like pseudo-science.

A less charitable explanation is that there is a systematic effort underway to contest and undermine actual climate science, including the assessments of the IPCC, in order to present a picture of reality that is simply false in support of climate advocacy. We might call that pseudo-scientific gaslighting.

The issues I document above are fairly obvious — and I invite contrary views, which I am happy to publish here at THB.

The easiest thing you can do to support THB is to click that “♡ Like”. More likes mean the higher this post rises in Substack feeds and then THB gets in front of more readers!

Thanks for reading! THB is reader supported, which means I work for you — Literally. I like it that way. You can find a readily accessible list of THB series here. THB is largely open access thanks to paid subscribers who have told me that they support my work so it can be available to all (even so, in 2024, about 15% of posts included paid-subscriber only content). Paid subscribers should look for the HB 2025 Home Office Pool tomorrow. Meantime, click that subscribe button!

The Grantham Institute IRIS model uses 42 years of data to create 10,000 years of tropical cyclones. I’m no climatologist, but using 42 years of climate data to characterize 10,000 years of climatological possibilities is certainly an interesting methodological choice.

Imperial College does not explicitly use this 7,000% value to characterize the increased likelihood. Perhaps because people might laugh.

This example assumes one Chido-like landfall per year. Reality is actually much less, meaning that it would be longer than 2,100 years.

This is consistent with data I published recently here at THB.

I do have to admit that the IPCC attribution standard is also hard to meet. An increase from 7,2% to 10,0% is real, no matter whether it takes 2.100 years to be more than 90% certain.

It's increasingly my believe that people are not rational, but they do like to rationalize. This process is everywhere in our society and we are all subject to it. Rationalisation is often used in the process of manipulation.

Codification of rationalisation is the end play.

Fortunately the "attribution science" did not need to explain why none of Michael Mann's 33 named storms achieved CAT6. ;-)