Today, Meta, the parent company of Facebook, announced that it would immediately stop using “fact checkers” to police the content on its platforms, which also include Instagram and Threads. Meta explained:

“In recent years we’ve developed increasingly complex systems to manage content across our platforms, partly in response to societal and political pressure to moderate content. This approach has gone too far. As well-intentioned as many of these efforts have been, they have expanded over time to the point where we are making too many mistakes, frustrating our users and too often getting in the way of the free expression we set out to enable. Too much harmless content gets censored, too many people find themselves wrongly locked up in “Facebook jail,” and we are often too slow to respond when they do.”

It’s about time.

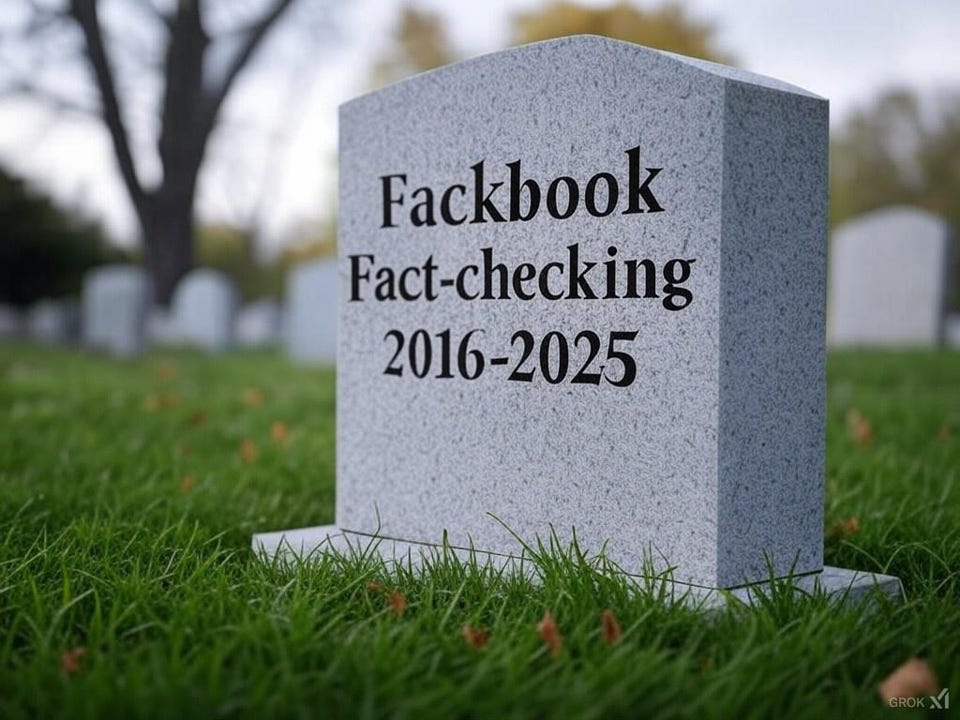

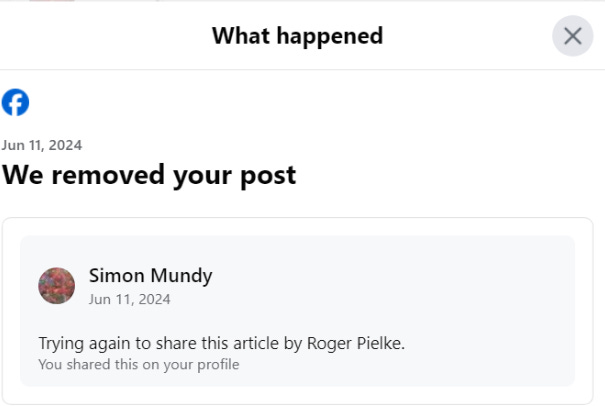

I am far from a disinterested observer here — The Honest Broker on Substack, what you are reading right now, has been deplatformed from Facebook for unknown thought crimes. Long time followers will know of many of my many experiences with self-appointed “fact-checkers.”1

Meta’s decision provides an opportunity to articulate why free expression is so important to both truth and democracy, and why efforts to reign in such expression is inimical to both.

Democracy, however defined, depends upon citizens and elites that are informed, however limited and imperfectly. Making decisions — that is, taking one fork in the road rather than others — that lead to desired outcomes depend upon some ability to understand cause and effect, action and consequence. Identifying desired outcomes depends upon the ability of all to participate in both identifying those forks in the road and participating in choosing which ones to take, recognizing that people will disagree about each.

These issues are far from new. Writing in The Atlantic in 1919, Walter Lippmann characterized what he saw to be “the basic problem of democracy.”

Lippmann argues that while there may have been a time when what people chose to believe did not matter for governance, in modern society, what people “believe about property, government, conscription, taxation, the origins of the late war, or the origins of the Franco-Prussian War, or the distribution of Latin culture in the vicinity of copper mines, constitutes the difference be tween life and death, prosperity and misfortune.” Understandings matter.

At the same time, Lippmann recognized that the world in which we live together defies understanding:

“The world about which each man is supposed to have opinions has become so complicated as to defy his powers of understanding. What he knows of events that matter enormously to him, the purposes of governments, the aspirations of peoples, the struggle of classes, he knows at second, third, or fourth hand. He cannot go and see for himself. Even the things that are near to him have become too involved for his judgment. I know of no man, even among those who devote all of their time to watching public affairs, who can even pretend to keep track, at the same time, of his city government, his state government, Congress, the departments, the industrial situation, and the rest of the world. What men who make the study of politics a vocation cannot do, the man who has an hour a day for newspapers and talk cannot possibly hope to do. “

A century later, the challenge to understanding has only become greater.

Lippmann further recognized that a quest for understanding is further complicated because public affairs . . .

“. . . involves the lives of millions, and the fortune of everybody. The jury is the whole community, not even the qualified voters alone. The jury is every body who creates public sentiment — chattering gossips, unscrupulous liars, congenital liars, feeble-minded people, prostitute minds, corrupting agents. To this jury any testimony is submitted, is submitted in any form, by any anonymous person, with no test of reliability, no test of credibility, and no penalty for perjury.”

The “basic problem of democracy,” according to Lippmann is that at once democracy depends upon somewhat accurate understandings of the world to inform collective decision making, but our ability to achieve accurate understandings is highly limited. Lippmann characterized the differences between “the world outside and the pictures in our heads,” with explicit reference to Plato’s allegory of the cave.

We act and decide based on the “pictures in our heads,” which may or may not conform to truth. Does the impossibility of fully understanding the world make democracy impossible?

Lippmann, and other American pragmatists, answered no — so long as enough of us commit together to trying to achieving the best understandings that we can to inform collective decision making in pursuit of shared interests.2 To paraphrase Lippmann in Public Opinion, the goal of politics is not to get people to think alike, but for people who think differently to act alike.

That brings us back to modern-day fact checkers.

There can be no doubt that the quest for reliable understandings of the world are made more complex by the “chattering gossips, unscrupulous liars, congenital liars, feeble-minded people, prostitute minds, corrupting agents.” At the same time, there are also legitimate differences of view among well-intentioned people, including those with sophisticated expertise. Telling the difference can sometimes itself be challenging.

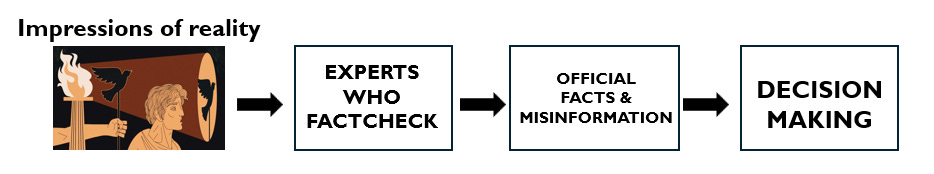

Wouldn’t it be great if we had an institution that could sort fact from misinformation, with those peddling the latter deplatformed so that they would be prevented from polluting the understandings necessary for the effective practice of democracy?

The underlying theory of democracy common to efforts to police public expression related to important issues is shown above, with experts empowered to render judgments on what is true and what is not. Truth might be central to democracy, but truth is not determined democratically, right? The appeal of such a model is obvious. This is the approach to content moderation employed by Facebook over the past eight years.

However, as Facebook has learned, official designations of truth and misinformation easily lead to censorship, are quickly politicized, and ultimately defeat the social and political engagement necessary to democracy. For some, of course, these might be viewed as features rather than flaws.

The appeal of the “fact-checking” approach to truth and decision making to experts is also obvious. Those with authority to determine what is true and who is to allowed to speak truth as they see it will necessarily play an outsized role in policy and politics. I often wonder if some experts are actually quietly opposed to democracy, preferring instead some form of technocracy or scientocracy, leaving the public and the politically undesirable behind altogether.

The policing of viewpoints on Facebook and other platforms began with subject matter experts, and quickly motivated the rise self-styled “misinformation experts” who claimed not only to be able to clearly identify misinformation and bad actors, but also to “inoculate” the ignorant among us against falsehoods. The hubris and self-aggrandizement on display does deserve some appreciation.

Of course, society is made possible by institutions that make formal judgments of truth — What time is it? How long is a meter? Is the vaccine safe? Where is the tornado headed?3

Yet, there are other sorts of questions where most of us would balk at being determined as institutionally-mandated truths — Is nuclear power safe? Do tariffs reduce GDP growth? Must we maintain 6 feet of distance during a pandemic? Is a fetus a child?4

Writing in the Financial Times in 2016, when Facebook began its strict content moderation practices, Isabella Kaminska presciently articulated what was wrong with official fact-checkers:

The idea all-powerful platforms like Google and Facebook should be charged with the responsibility of strategically filtering and determining what constitutes fake news is not just questionable but frightening in the Orwellian Newspeak sense of the word.

The rot at the core of media has little to do with the propagation of fake news on the fringes. Alternative news sites and underground press with questionable journalistic practices have been a phenomenon since forever. In free societies, the public sphere tolerates single-issue publishers, special interest groups or anti-establishment newsletters, because we know that for every outlet which propagates nonsense there’s another that might be ahead of the curve on a topic of great cultural, commercial or political significance.

Accepting the fringes — which includes fake news — is what liberty and a free press is about. It’s our greatest strength, especially when positioned within the constructs of a fair and reasonable slander, libel and defamation framework. Suppressing marginal views is not the answer.

Kaminska invokes liberty, the same concept that is central to Lippmann’s defense of both democracy and free expression expressed a century earlier (emphasis added):

We cannot successfully define liberty, or accomplish it, by a series of permissions and prohibitions. For that is to ignore the content of opinion in favor of its form. Above all, it is an attempt to define liberty of opinion in terms of opinion. It is a circular and sterile logic. A useful definition of liberty is obtainable only by seeking the principle of liberty in the main business of human life, that is to say, in the process by which men educate their response and learn to control their environment. In this view liberty is the name we give to measures by which we protect and increase the veracity of the information upon which we act.

Truth — the veracity of information — is best approached collectively, through disagreement, debate, experience.

In its release today, Meta recognizes that its approach to content moderation became a tool of censorship:

When we launched our independent fact checking program in 2016, we were very clear that we didn’t want to be the arbiters of truth. We made what we thought was the best and most reasonable choice at the time, which was to hand that responsibility over to independent fact checking organizations. The intention of the program was to have these independent experts give people more information about the things they see online, particularly viral hoaxes, so they were able to judge for themselves what they saw and read.

That’s not the way things played out, especially in the United States. Experts, like everyone else, have their own biases and perspectives. This showed up in the choices some made about what to fact check and how. Over time we ended up with too much content being fact checked that people would understand to be legitimate political speech and debate. Our system then attached real consequences in the form of intrusive labels and reduced distribution. A program intended to inform too often became a tool to censor.

Reconciling expertise and democracy is a fundamental challenge of our time. As Lippmann and other pragmatists realized, such reconciliation will always be strongly contested and deeply imperfect. Such is the nature of politics. But if we are going to live together, we must begin with a shared commitment to liberty, as envisioned by Lippmann more than a century ago.

More from the wisdom of Walter Lippmann at THB: Intellectual Hospitality and Genuine Debate. I also highly recommend Dan Williams Substack on these issues — Conspicuous Cognition.

The easiest thing you can do to support THB is to click that “♡ Like”. More likes mean the higher this post rises in Substack feeds and then THB gets in front of more readers!

If you are a new visitor, Welcome! Read all about THB here. THB is reader supported, which means I work for you — Literally. I like it that way. You can find a readily accessible list of THB series here. THB also has a portal with paid-subscriber only content. So click that subscribe button!

One of my favorites was the time that MIT’s Kerry Emanual, working for Facebook at a group called Climate Feedback, confidently claimed: "economic damage, normalized by world domestic product... from weather-related natural disasters have been increasing greatly." That claim is of course is undeniably false. Kerry is a good scientist and a decent person, which shows that getting wrapped up in pathological practices does not require malintent.

While simultaneously recognizing the reality of “chattering gossips, unscrupulous liars, congenital liars, feeble-minded people, prostitute minds, corrupting agents.”

In my book that carries the name of this Substack, such questions exist in the world of “tornado politics.” Scientific advisory and assessment bodies are often tasked with summarizing and assessing what we know and what we don’t know. Such assessments typically inform decision making, they do not become legislated as truths.

In my book that carries the name of this Substack, such questions exist in the world of “abortion politics.”

Had Kamala Harris been elected president, would Meta have made this announcement?

I'm with you on just about all of what you lay out, Roger, particularly the need for a comfort level with acting not only under uncertainty but also under complexity (varied stances by experts with varied disciplines and value orientations). The problem is that the "community notes" alternative - at least the model at X (which Zuckerberg alluded to) faces enormous challenges if it is to be useful. I speak from experience, having participated in Notes for more than a year. One big one is that the process can be (and has been) gamed as flocks of ideologically driven users swarm with "NNN" posts (note not needed). That delays any correction long enough that the fakery spreads like crazy and correctives are posted far too late to be of use: https://x.com/Revkin/status/1876630289453138340