I’m writing this week from Tokyo, where I am participating in a fascinating symposium on “Energy Security and Global Warming in an Increasingly Uncertain International Climate,” sponsored by the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Public Policy (GraSSP) and the Institute of Energy Economic, Japan (IEEJ).1

My contributions to the symposium focused on global rates of decarbonization, consistency (or not) of global and national decarbonization rates with Paris Agreement targets, and offering my perspectives on the upcoming U.S. election for climate and energy policies. My slides are shared with THB paid subscribers at the bottom of this post. As is usual at such events, I have learned a lot and have especially enjoyed the chance to catch up with colleagues old and new — Japan is a unique place and I’ve been privileged to visit many times over the past decades.

Japanese politics are especially interesting right now. The current Prime Minister — Fumio Kishida — announced in August that he would not seek reelection as president of the Liberal Democratic Party (LPD), with the party election taking place later this month on 27 September. That means he will necessarily be stepping down as prime minister and the next LDP leader will become the next Japanese prime minister.

The current race for the LDP president and next Japanese prime minister has a very large field and lots of drama. The Japan Times reports:

Amid a crowded race for the ruling Liberal Democratic Party leadership, two front-runners vying to be Japan’s next prime minister are at odds over when to call a snap election, all while a dark horse candidate gains momentum in the polls ahead of the Sept. 27 vote.

The two leading contenders — former environment minister and media darling Shinjiro Koizumi, the 43-year-old son of ex-Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, and 67-year-old former defense minister Shigeru Ishiba — hold differing views on when they would call a snap election should either of them become prime minister.

Koizumi reiterated during an appearance on an NHK program Sunday that if it were up to him, he would call for dissolving the Lower House “as soon as possible.” In contrast, Ishiba said he would not dissolve the body immediately, emphasizing that the decision required considering the political situation at that time.

“We cannot make decisions based solely on the Liberal Democratic Party’s preferences,” Ishiba said.

But Koizumi and Ishiba may have more competition as the race heats up, with support for economic security minister and conservative firebrand Sanae Takaichi rising, especially among LDP rank-and-file voters.

One important (but not the top domestic headline) issue in the leadership contest is Japanese energy policy. Energy Intelligence explains:

The upcoming election for the leadership of Japan's ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) will determine who will take the realms from Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, and may test the extent to which shifts in prime minister can move the needle in restarting Japan's nuclear fleet more than a decade after the March 2011 Fukushima Daiichi disaster that saw most of it turned off. Despite the "nuclear revival" initiative pursued by Kishida since he took power in 2021, only 12 of the country's reactors have been restarted, of which 10 are currently operating, as compared to 54 in 2010, and a significant portion of the Japanese nuclear fleet remains mired in regulatory safety reviews and local hesitancy to agree to restarts.

The campaign for the LDP presidency will not be focused on nuclear power, but comes just as discussions are heating up on Japan's seventh basic energy policy, which is slated for finalization by Mar. 31, 2025. After the party poll is completed on Sep. 27, the new president of the LDP — the conservative party that has ruled Japan almost continuously since 1954 — will be elected prime minister in a special session of the House of Representatives and will have the option of calling a general election. Kishida’s three-year administration is ending less because of the failure of major policies than the cumulative impact of the exposure of the extensive influence of the far-right former “Unification Church” in the LDP and a series of election financing and slush fund scandals.

A record nine candidates secured the required endorsement of at least 20 LDP parliamentarians to run for the LDP’s top post. After votes are counted Sep. 27, only two will advance to the likely runoff vote the same day that will be dominated by LDP parliamentarians.

Two of the three apparent frontrunners might adjust Kishida's focus on nuclear in favor of a stronger emphasis on deploying renewables and aiming for energy efficiency: namely, former environmental minister Shinjiro Koimizu (43), the son of ex-prime minister Junichiro Koizumi, and former party Secretary-General Shigeru Ishiba (67). Economic Security Minister Sanae Takaichi (63) would likely follow Kishida's line on nuclear, one senior industry professional told Energy Intelligence. Rounding up the top four leaders in the polling is Digital Minister Taro Kono (61), who has lately moderated his critical stance toward nuclear power.

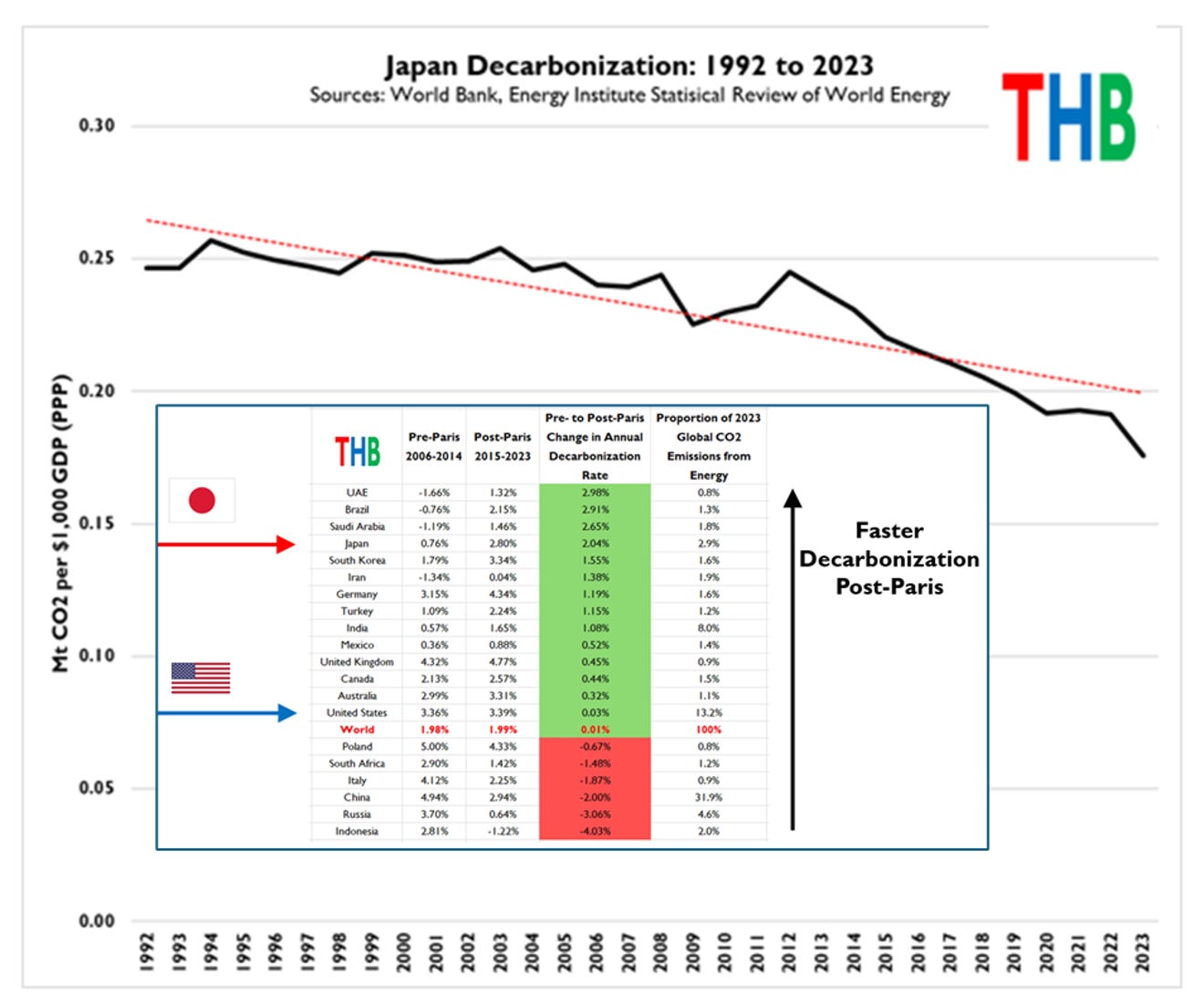

Japan faces an energy trilemma — seeking to simultaneously balance economic growth, energy security, and meeting international emissions reductions commitments. The figure below shows that Japan has a relatively impressive record of post-Paris decarbonization as compared with other countries, even with its post-Fukushima nuclear shutdowns.

However, the devil is in the details — accelerated Japanese decarbonization has a lot to do with a falling Japanese population in the context of continuing economic growth, and reductions in overall energy consumption — a unique suite of characteristics that cannot be applied to many places around the world.

Like every other country, Japan wants to sustain and even accelerate economic growth, requiring continuing expansion of trade, while maintaining its commitments to emissions reductions. Of course, whether expressed or not — the former trumps the latter. It is an iron law.

Tatsuya Terazawa, Chairman of the IEEJ, has explained that the policies of outgoing Prime Minister Fumio Kishida have aimed to hit the sweet spot where the imperatives of the energy trilemma meet:

The Kishida Cabinet decided on the Basic Direction of the GX Strategy in February 2023. (GX stands for Green Transformation). The objective of the GX Strategy is to accelerate the energy transition while ensuring economic growth. The Strategy set out the goal that 150 trillion yen, or more than 1 trillion USD, would be invested by the public as well as the private sector in the next ten years to realize the energy transition. The Government pledged to provide 20 trillion yen (140 billion USD) during the next 10 years to support the energy transition.

The scale of the budget support and the 10-year long commitment are both unprecedented in Japan.

GX transition bonds will be issued to finance the government support and they will be paid back by 2050 through the revenue generated by the new carbon pricing system. This design is expected to help maintain a fiscal discipline. The carbon pricing system will have two pillars. Emissions trading system will be started in 2026 and fossil fuel charges, a de facto carbon tax, will be introduced in 2028. The revenue from these two pillars of carbon pricing will be used to pay back the GX transition bonds.

The carbon pricing system is designed to ensure that the burden of these two mechanisms on the industry will be kept within the level of the expected burden on the industry through FIT (Feed-in-Tariff) /FIP (Feed-in-Premium) and the Oil and Coal Tax. This design is expected to ensure the competitiveness of the Japanese industries.

These innovative designs to ensure fiscal discipline and industrial competitiveness could be a model for countries facing the dilemmas between climate change policy, fiscal soundness and industrial competitiveness.

Out of the 20 trillion yen of fiscal support, three trillion yen has been ear marked for hydrogen/ammonia. Through the Diet, the Japanese Government has already legislated that a mechanism will be provided to offset the cost differential between hydrogen/ammonia and conventional energies and to help develop the necessary infrastructure to receive hydrogen/ammonia.

To complement such fiscal support, carbon pricing and other regulatory reforms will also be introduced to promote hydrogen/ammonia. The set of policies to promote hydrogen/ammonia is arguably the strongest in the world today.

A new government affiliated organization named the GX Acceleration Agency has been established to provide loan guarantees and equity to help the financing of energy transition projects.

In addition to hydrogen/ammonia, energy efficiency, next generation fuels and CCUS will be the major sectors to be supported. Strengthening the manufacturing of batteries, electrolyzers and the next generation solar PVs are also part of the GX Strategy.

Whether the next Prime Minister continues PM Kishida’s policies is completely uncertain. The expected approaches of the leading LDP candidates span a wide range of possibilities. In particular, the policies of Sanae Takaichi would likely be more in line with energy realism than those of her opponents.

Back in 2009 (another sign, besides my knees, that I am getting up there), I published an evaluation of Japan’s climate policy of the time — which was exceedingly ambitious and we-now-know unfulfilled set of aspirations, then-called “mamizu” (genuine clear water — i.e., we do what we say) emission reduction policy.

Back then I concluded based on my evaluation:

If climate policy is to be about more than symbolic exhortation, then it will necessary for goals to be more than aspirational. Japan’s Mamizu climate policy targets for 2020 and 2050 announced in mid-2009 were exceedingly ambitious, and if they are to be criticized, it should be for being too aggressive, not too weak. Should Japan actually succeed with respect to a short-term target of the magnitude implied by the Mamizu climate policy, then it will have achieved a carbon intensity of its economy lower than that of France in 2006 by the end of the decade, representing a decrease in emissions per unit of GDP of about 33%. If the world economy were to be as carbon efficient as implied by Japan’s 2020 target, then global carbon dioxide emissions in 2006 would have been only 40% of their actual value.

Regardless of the nature of changes to the composition of the Japanese government in the future, there is considerable merit in encouraging Japan to actively seek to achieve its Mamizu climate policy because its successes and shortfalls will provide a valuable body of experience to other countries seeking to achieve similar goals. Should Japan choose to depart from its proposed Mamizu climate policy to one based on (even more) impossible targets and timetables than they may find themselves the subject of international applause rather than condemnation. At the same time such a shift would signify a desire to meet the symbolic needs of international climate politics while sacrificing the practical challenge of decarbonization policy. Conventional approaches to climate policy have thus far borne little fruit, but that is a topic that goes well beyond this brief analysis. Diversity in climate policy should be encouraged.

While no one could have anticipated Fukushima, even so, I did get that one right — of course, balanced out by the ones I got wrong. Japan, like the rest of the world, has struggled to achieve rates of decarbonization anywhere close to those implied by the Paris Agreement. At the same time, Japan’s demographic changes place it well ahead of the rest of the world, which may not be far behind.

Consequently, it is likely that Japan offers the rest of us a glimpse into the global future — a rich country with one of the world’s largest economies, with a falling population, with demands for economic growth and increasing energy demand to meet expectations of continuing technological innovation and a growing economy, while at the same time wanting to dramatically reduce carbon dioxide emissions. A trilemma indeed.

Pay particular attention to Japan’s deliberations over nuclear energy. I have a degree in math and yet can’t seemingly square the math of the Japanese energy trilemma without envisioning a renewed commitment to nuclear energy — and we shall see how that works out in short order.

Watch this space, it just might tell us something about our collective futures!

Your financial support of THB has helped to make this trip and this reporting possible (thanks also to GraSSP and IEEJ for their support). I receive no research funding other than that which comes from THB supporters, and I like it that way! I invite your comments and questions — let’s discuss. The event organizers will soon post all presentations from the symposium online and I’ll share them when available. Meantime, you can find mine below. If you are one of the thousands of new subscribers here at THB, you can find out what THB is all about here. Honest brokering is a group effort!