Not long ago the New York Times asked some of its most prominent columnists to write about something important that they had gotten wrong. It was an interesting exercise and one I thought worth repeating here at The Honest Broker.

Below I discuss a few important things that I got wrong in my research. At the outset, let’s distinguish between making a mistake — like a typo or data error — and getting something fundamentally wrong. Anyone who writes or works with data will be familiar with mistakes, which we work hard to avoid but which inevitably occur. When they do, it is both important and easy to correct them. As someone who does much of my work in public, I’ve come to appreciate the many eyes on my writing and analyses that help to identify mistakes.

Being wrong is different. Correcting wrongness requires not just a simple fix, but often changing how we think about the world, which can be pretty difficult. The good thing about being wrong is that it provides a great opportunity to learn, and hopefully develop less wrong ways of thinking about the world. Of course, there are multiple legitimate ways to think about the world, so identifying wrongness has added complications, as sometimes one person’s wrong is another’s right.

Over the past few decades, I’ve written hundreds of papers, many books and millions of words in commentary, blogs and Tweets. Like anyone who does research and writes, I’ve made a lot of mistakes, fortunately none none so significant that they impact global finance. I have also been wrong about some important things that are pretty unambiguously wrong, not just reflective of differences of worldview or opinion.

Here are two of the most significant.

Projections of Increasing Hurricane Damage

In a 2005 presentation to the American Geophysical Union, I argued that by 2025, future coastal development and economic growth could lead to a $500 billion hurricane. That projection was featured in the New York Times and other major media (this was back when our normalization work was routinely featured in the media — that is no longer the case):

To better understand the potential for catastrophic damage from future hurricanes, scientists are looking to the past.

And the future looks very expensive, the scientists said this week at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union. With wealth and property values increasing, and more people moving to vulnerable coasts, by the year 2020 a single storm could cause losses of $500 billion -- several times the damage inflicted by Hurricane Katrina.

Roger A. Pielke Jr., director of the Center for Science and Technology Policy Research at the University of Colorado, presented preliminary results of a study that retraced the path of hurricanes from the past 105 years and calculated the havoc they would wreak on the present-day United States landscape.

I was wrong.

It is conceivable that in 2025 a single hurricane could cause damage approaching $300 billion (e.g., a repeat of the 1926 Great Miami Hurricane), it is difficult to envision a $500 billion event. To be sure, a single $500 billion event is conceivable under certain assumptions about the future, but it is also conceivable to envision a scenario under which improved patterns of development and structural mitigation of the built environment makes such an outcome impossible.

My assessment of the underlying dynamics was sound — more people, more wealth, more property leads to more damage. What I got wrong was my projection of how fast damage potential would increase. I simply did not consider that economic growth and coastal development might proceed over the subsequent 20 years at a rate less than the past.

Lesson learned.

The British Climate Change Act

About 15 years ago I published detailed policy analyses of the climate policies of Australia, Japan and the United Kingdom. The Australian and Japanese case studies have stood the test of time remarkably well. The UK analysis, not so much. What happened?

First, a brief bit of background on the studies. In each study I applied the Kaya Identity to evaluating the implied rates of decarbonization under (at the time) current government policies for carbon dioxide emissions reductions. The Kaya Identity allows us to calculate the carbon intensity of the economy, and to evaluate rates of reduction in that metric implied by targets and timetables of emissions reduction policies. Implied reductions require real-world changes in the various component factors of the Kaya Identity, which can be evaluated in terms of their plausibility.

Based on a projection of decarbonization rates under several alternative scenarios I concluded of the targets and timetables of the UK Climate Change Act:

Given the magnitude of the challenge and the pace of action, it would not be too strong a conclusion to suggest that the Climate Change Act has failed even before it has gotten started. The Climate Change Act does have a provision for the relevant minister to amend the targets and timetable, but only for certain conditions. Failure to meet the targets is not among those conditions. It seems likely that the Climate Change Act will have to be revisited by Parliament or simply ignored by policy makers. Achievement of its targets does not appear to be a realistic option.

I was wrong.

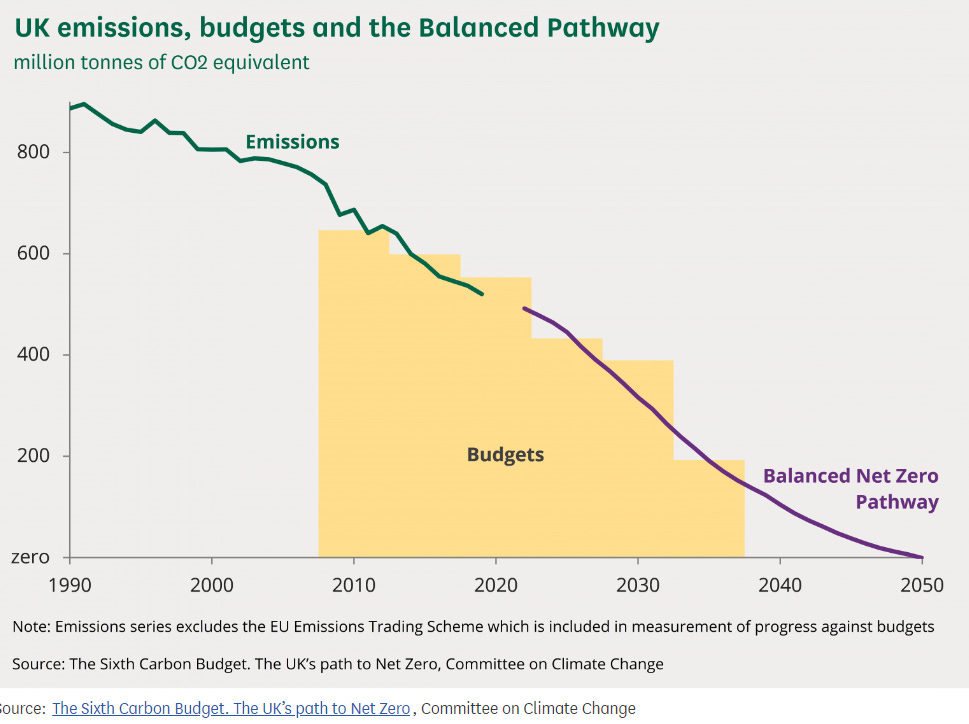

As you can see in the figure below UK emissions have plummeted since 2008, when my paper was published, and largely in line with the targets of the UK Climate Change Act.

What did I get wrong?

The main factors were my projected rates of UK economic growth (reality has been much less) and the sectoral shifts in the UK economy, due to the global financial crisis, Brexit and the pandemic.

You can see in the figure below that overall energy consumption in the UK decreased significantly after 2005, mainly due to the changing composition of the UK economy and slow growth. Other factors that I did not consider are the accounting rules associated with bioenergy (e.g., burning imported wood) and energy supply from Europe.

Looking back now, I should have read what I actually wrote in the paper because I was on the right track.

[T]he focus on emissions rather than on decarbonization means that it would be very easy for policy makers to confuse emissions reductions resulting from an economic downturn with some sort of policy success.

The dynamics underlying decarbonization embodied in the Kaya Identity are sound. In this case I suffered a failure of imagination — in thinking the future would be just like the past. It wasn’t. The idiosyncratic and unique dynamics of emissions reductions of the UK since 2008 mean that the country does not offer a particularly useful blueprint for others to adopt to meet decarbonization targets.

Lessons Learned

Being wrong offers an opportunity to learn. For me, the two cases above reinforced something I know well and write about a lot — as the old saying goes: prediction/projection is difficult, especially about the future. Some of these lessons show up in a new paper of ours, led by my colleague Matt Burgess, on “Optimistically biased economic growth forecasts and negatively skewed annual variation.”

In addition, in recent years I and colleagues have done a lot work on formalizing conceptions of scenario plausibility. These exercises have helped me to better appreciate that stylized projections of the future — such as in the three Kaya Identity papers linked above — may often provide a reliable guide to the future, except when they don’t. Knowing the difference, to the extent that is possible, is essential to producing effective policy analyses.

Hi Roger

Great post. I’m particularly interested in your newer analysis on the UK.

I’m UK based. I feel that the direction of travel for the Energy Transition here is obvious (ie more wind, modular nuclear, some solar & more heat pumps for domestic heating & electric cars). The speed and final destination of these changes is very uncertain. Issues such as energy storage seem to have no immediate solutions.

Whilst I think carbon emissions will continue to decline, I don’t think that Net Zero by 2050 is remotely possible.

As you identify, I think there are also huge issues about the UK simply closing down industries and importing goods whilst ignoring the associated emissions. Also, issues around carbon accounting for biofuels.

I think the UK is a bit of a live experiment at the moment. I’m concerned that the government simply double-down on simplistic policies that continue to shut down industry and clamp down on activity like transport.

I would love to see more analysis on this and would really like to see more analysis that normalises for industrial offshoring.

Many Thanks

Duncan

Roger

Haven't you missed something very important? We've destroyed our indigenous manufacturing capability and have outsourced it all to China etc. The UK economy now runs on cheap imports from countries like China and India. Surely if you account for the carbon emissions associated with our imports the picture would look very different indeed?