Writing in the Wall Street Journal earlier this week Greg Ip and Janet Adamy explored the possibility that the world’s population may peak and begin to fall far sooner than demographers have previously projected:

The world is at a startling demographic milestone. Sometime soon, the global fertility rate will drop below the point needed to keep population constant. It may have already happened.

Fertility is falling almost everywhere, for women across all levels of income, education and labor-force participation. The falling birthrates come with huge implications for the way people live, how economies grow and the standings of the world’s superpowers.

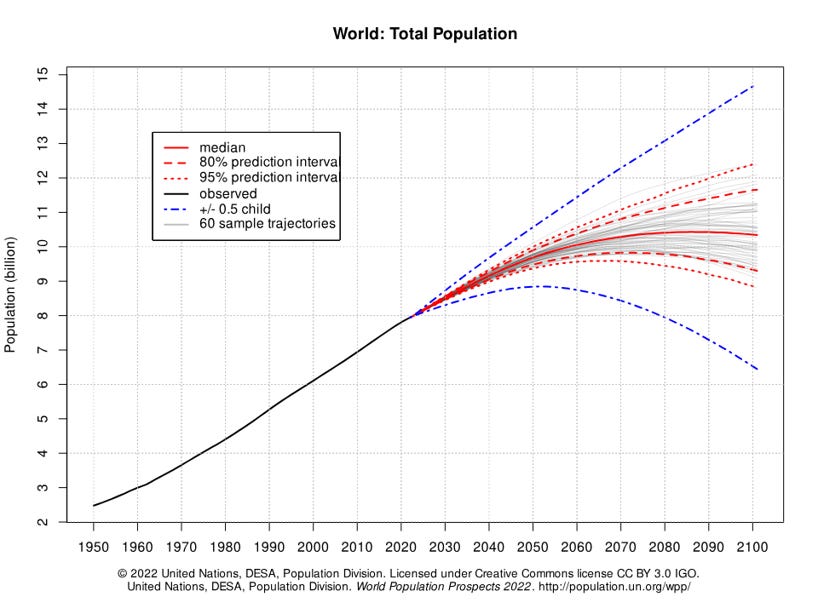

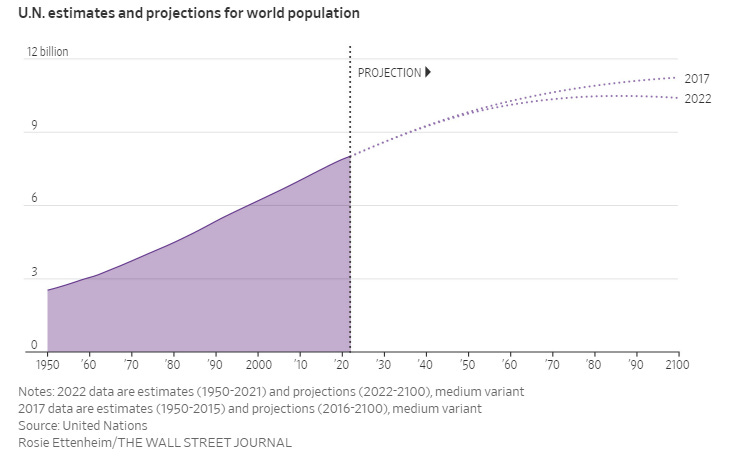

The United Nations, in its World Population Prospects 2022, projected in its medium variant scenario that global population would peak in the 2080s at about 10.4 billion people. The WSJ reports that figure represents a substantial drop from U.N. projections just five years earlier: “In 2017 the U.N. projected world population, then 7.6 billion, would keep climbing to 11.2 billion in 2100.”

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington in 2020 projected a global population in 2100 of about 1.5 billion less than the United Nations:

In the reference scenario, the global population was projected to peak in 2064 at 9.73 billion (8.84–10.9) people and decline to 8.79 billion (6·83–11·8) in 2100.

Both the U.N. and IHME foresee projected 2100 population to be less than demographers had previously projected. The trend in population projections for these organizations is down.

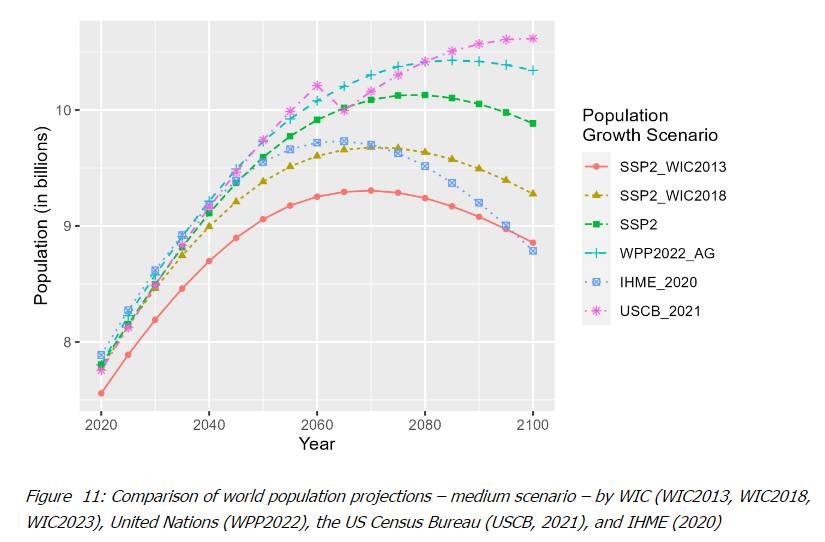

In contrast, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in a recent update to its Shared Socioeconomic Pathways scenarios increased its 2100 population projection by more than 1 billion people in its “middle of the road” scenario:

[A]ccording to SSP2, which is the middle of the road scenario, the world would peak in 2080 at 10.13 billion and slowly decline after that to reach 9.88 billion in 2100. Compared to the previous exercises, the world population would peak later and at higher level of total population. WIC2018 [its 2018 update] had its peak happening in 2070 at 9.7 billion, with the world population at the end of the century at 9.3 billion. WIC2013 [the original projections of the SSPs] again projected lower population growth, peaking at 9.4 billion in 2070 and declining to 8.9 billion by 2100.1

Even though IIASA has updated its population projections in 2018 and 2024, the SSPs that are used in climate research continue to rely on the original 2013 scenarios.2

The somewhat busy figure below shows the three IIASA SSP2 projections (WIC2013, WIC2018, and the 2024 version) along with the UN medium variant I showed above (WPP2022_AG), and the IHME 2020 projection (along with another extreme outlier that I do not discuss here from the U.S. Census Bureau 2021).3

By increasing their 2100 population estimates since 2013, the SSPs are moving in a different direction than the UN projections, which are trending down (shown below) and are expected to trend further down in the next update to be released later this year.

I asked Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, of the University of Pennsylvania, about his research cited by the WSJ and he replied with a link to their recent paper and some additional comments (quoted here with his permission):

We put together a world database of demographic transitions and document that the falls in fertility across the world are becoming faster, i.e., once fertility starts dropping, the speed is much higher than in the past. Recent evidence in countries in Asia and Latin America (Latam) is quite astonishing. In fact, I am writing a follow up paper about the fertility collapse in Latam. At this moment, nearly all Latam has a fertility rate BELOW the US, with extreme cases like Chile at 1.1 (and likely to be below 1 in 2024). I wonder how many people in the US is aware that Brazil or El Salvador have lower fertility rates than California.

I find both the paper and his arguments to be very compelling. Fernández-Villaverde also argues under the dynamics of a demographic transition that GDP becomes less useful as an indicator of economic performance:

We argue that GDP is becoming an increasingly misleading indicator of economic performance as populations age and hence the age composition of the population. The most striking case is Japan. if you measure GDP per working-age adult or GDP per hour worked, Japan has outperformed all advanced economies in the world since 1999. There is no "Japanese stagnation," just fewer Japanese workers. Not great news to pay back public debt, but monetary policy or absence of aggressive economic reforms are not the reason for anything bad in Japan.4

My takeaways:

The climate scenario community is presently far out of step with the views of the UN and IHME on population projections to 2100, and moving in the opposite direction;

Regardless, as we have argued before, the scenarios that inform ALL of climate research and policy are far too important to be single-threaded through a single institution and a small group of researchers;

More broadly, at present it is eminently plausible that the world is in the early stages of a demographic transition toward lower fertility rates and slower increases in population, leading sooner than expected to a global population peak and decline sometime in the middle part of this century;

In the portfolio of possible futures that we consider for long-term policy and planning, we should increasingly consider such scenarios, as they represent fundamental changes from all scenarios that foresee continued population growth through the century;

Such scenarios of population decline will have less dramatic future climate changes but will introduce other significant issues, like paying off public debt, sustaining economic growth, and covering social safety nets and pensions.5

Watch this space!

❤️Click the heart if you like babies!

I invite you to comment, critique, offer pointers to relevant material, and discuss. THB is reader supported and is (mostly) freely available to all thanks to the generous support of engaged members of the THB community. Thank you for making my work possible and sustainable! Learn more about THB here.

Interestingly, the 2013 IIASA projection is more in line with the 2020 IHME projection than is the 2024 IIASA projection.

These unincorporated updates to the SSPs reveal a fundamental weakness in how climate science uses climate scenarios. Once created, the scenarios become locked in (for various reasons, including institutional inertia) and inevitably become outdated.

That USCB projection appears to show the world losing 250 million people between 2060 and 2065. I have no idea why this happens in that scenario.

For more along these lines, see the recent work of my collaborator Matt Burgess and colleagues.

I’ll hypothesize that some in the climate community will resist or oppose scenarios of demographic transitions to lower/sooner population peaks and declines because of their potential to alter dire climate projections.

Excellent work sir. Thank you. A question. You hypothesize that some in the climate community will resist suggestions of demographic change. I agree with that hypothesis, but how does it reconcile with those in the climate community who wish to cull population, which you wrote about last week. That essay, by the way, was downright scary, to me. That we have responsible people who would wish for the collapse of civilization suggests our times are no better than they were in 1935.

One of my favorite views on this comes from Hans Rosling's 2018 book, Factfulness. In it are two charts showing the same basic information: Children surviving to age 5 and family size (babies per woman). Each chart is divided into two separate groups: Developing countries and Developed Countries. One chart is as of 1965. The other is as of 2017.

In the 1965 chart, there are 125 countries including China and India in the Developing Country group.. In those countries, women have more than 5 children, on average, and more than 5% of children died before their 5th birthday. In the Developed country group, there were 44 countries with family size of fewer than 3.5 children and child survival rates above 90%.

IN 2017, the picture had completely changed. The Developing country box contains only 13 countries (6% of the world's population) and most of the world's population is now in the Developed country box.

As countries have made the shift from Developing to Developed extreme poverty has been vastly reduced and the populations are able to sustain smaller families with a better life style.

Fifty years ago and earlier, we could not imagine a future with these demographic changes and the thought of increasing population was baked in.

As the adage goes, "In theory, theory and practice are the same, in practice they are not." The dynamics of family life have changed and that will drive population growth or decline.