Can We Reach Net-Zero and Achieve Modern Energy Services for All?

Four Answers Illustrate today's Four Positions On Energy and Climate

Last night at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, I had a chance to debate Steve Koonin, a professor at New York University, on the merits of policies focused on achieving net-zero carbon dioxide emissions in the second half of this century. It was a fun night and afterwards, I was especially pleased to hear from students and members of the community that they appreciated seeing experts disagree without being disagreeable.1

Preparing for last night got me thinking about the nature of debate over climate and energy policies. For a long time debate has been framed as being narrowly about climate science — deniers vs. alarmists, to ungenerously oversimplify. On both sides, this framing is encouraged by scientists, as it elevates their expertise in political settings. I’ve long thought that the two-sides of this framing actually embrace each other in order to justify their own position. After all, if views on science actually determined policy then defeating the other side would be paramount.

Of course, as THB readers well know, debates over science do not determine political outcomes. As Walter Lippmann once said, the goal of politics is not to get everyone to think alike, but to get people who think differently to act alike.

Today, debate over climate and energy policies is finally and thankfully moving well beyond the science-as-politics framing. Below I suggest that, today, four different stances can be found on climate and energy.

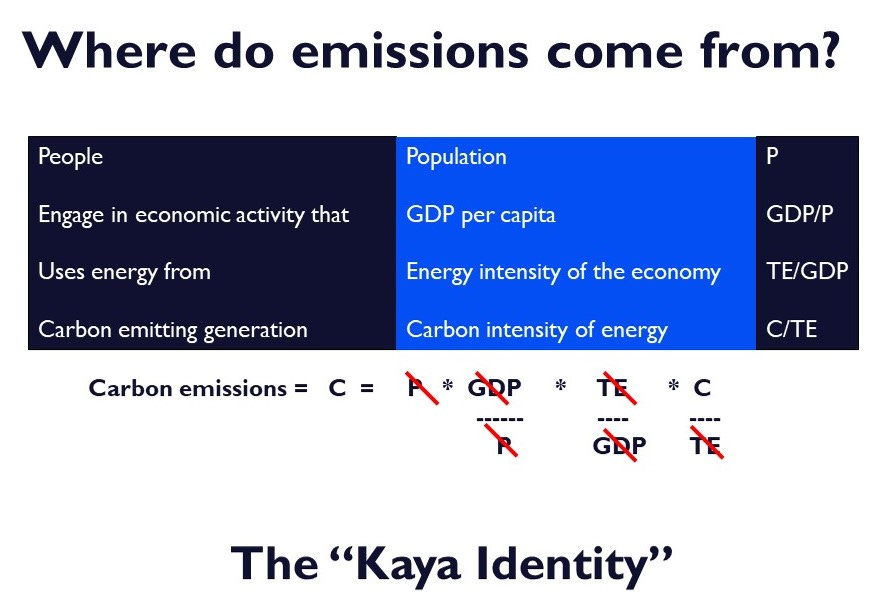

To characterize these stances, let’s start with the Kaya Identity.

The Kaya Identity plays a central role in my book The Climate Fix because it provides a straightforward and readily comprehensible framework for analyzing the challenges of emissions reduction. The Kaya Identity tells us that we have four — and only four — policy levers with which to reduce emissions.

These are shown in the image above from my opening remarks last night, and they are:

Population

Per capita GDP

Energy intensity of the economy

Carbon intensity of energy

That’s it. Emissions reductions policies will only reduce emissions if they influence one of these four factors.

It was the Kaya Identity that lead me to coin the iron law of climate policy, which simply acknowledges the political reality that we are not going to use the first two factors of the Kaya Identity — GDP — as a tool to reduce emissions. In fact, policy makers with the support of the public are going to continue to pursue GDP growth.

Right away, we should see that talking about carbon dioxide emissions without also talking about economic growth misses a lot, and is apt to mislead. We want GDP to grow and emissions to decrease, and the Kaya Identity tells us that these two goals can be in conflict if we focus only on emissions.

A better metric for understanding the challenge of achieving net-zero carbon dioxide emissions is thus decarbonization of the economy. The precise definition of this metric is shown in the figure below, also from my opening remarks last night, which applies some simple math to the Kaya Identity.

A reduction in the ratio of emissions to GDP indicates that energy technologies are improving. But a reduction does not necessarily mean that overall emissions will decrease — the rate of reduction must exceed the rate of GDP growth.

Decarbonization rate < rate of GDP growth = emissions increase

Decarbonization rate = rate of GDP growth = emissions plateau

Decarbonization rate > rate of GDP growth = emissions decrease

The sustained rate of decarbonization over many decades will determine if and when we achieve net-zero carbon dioxide.

Let’s look at some data. The figure below shows decarbonization of the global economy since 1990.

The data shown above has two important features:

First, decarbonization of the global economy predates climate policy. In fact, decarbonization is a process that has been underway for much of the past century. Climate policy focused on achieving net zero is thus not about doing something new or different, but accelerating a process that is already in place.2 That’s very good news, because it is always easier to sail with a prevailing wind.

Second, since 1990 the rate of global decarbonization is well approximated by a linear trend (the red dotted line). That means that efforts to accelerate the rate of global decarbonization have not had much effect.3 Since 2015 the global economy has decarbonized at a rate of just over 2% per year — depending on your target for net-zero that rate needs to be 6%, 7%, 8% or more, a huge challenge.

The table below outline four different perspectives on energy and climate based on two dimensions: one’s views on whether the world will consume much more energy in the future and one’s views on the feasibility of achieving net zero carbon dioxide.

Let’s consider each quadrant in turn:

Millenarians. These include groups such as Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil. Some believe that the end is nigh and that we need to starting building our bunkers.4

Neo-Malthusians. These include degrowthers, neo-colonialists who wish to limit energy in poor countries, and the old-school population control crowd. They see the first two elements of the Kaya Identity as central to achieving net-zero.5

Energy Realists. These include people like Steve Koonin and Vaclav Smil who look at rates of decarbonization of the global economy consistent with achieving net zero carbon dioxide and judge pessimistically that it cannot be done (or cannot be done this century).6

Ecomodernists. These are people like myself and The Breakthrough Institute who look at the history of innovation in areas such as agriculture and health and optimistically believe that similar incredible technological gains can be made in energy systems over the 21st century.7

In the past, debate over climate and energy has typically pitted Neo-Malthusians against Energy Realists, often with climate science at the center of the debate, with deeper issues underneath, often unstated.

As debates over energy displace debates over the fundamentals of climate science, the main fault line going forward will be between Energy Realists and Ecomodernists, between innovation pessimism and innovation optimism.8 I have a lot of time for Energy Realists — they are absolutely correct about the magnitude of the challenges associated with energy system transformation. I have often highlighted those challenges here at THB.

At the same time, the fact that we do not know today how to achieve net zero by the end of the century should not prevent us from even trying. A key difference of perspective on display last night was my insistence that we should take on the net zero challenge and Koonin saying explicitly that we should not.

In my closing comments in Chapel Hill, I observed that when my grandfather (RIP) was born in 1923, a century ago, the world had 2 billion people and life expectancy was about 35. Had we asked agricultural and health experts of that time how the world would feed 8 billion people and more than double life expectancy by 2023 the only honest reply would have been — Hell, if I know!

But thank goodness we tried.

We humans do know how to innovate. We may not know how that last ton of carbon dioxide emissions will be eliminated,9 but we sure can act to move the dial on decarbonization of the global economy up from 2% per year. Put me down on the side of optimism about our climate and energy future.

How about you, what quadrant do you fall into?

Thanks for reading! Comments welcomed — as usual please stay on topic. If you’d like to make a comment on another topic, no problem, the archives here probably have a post where you can discuss that. Please share around and click that little heart at the top. If you are not yet a subscriber, please sign up and join the community. And if you are a subscriber, thanks for your support — THB is a group effort.

I’ll post up the full video of the debate at my personal homepage when available.

Historically, decarbonization of the global economy has been driven by changes in the energy intensity of economic activity. To achieve deep decarbonization will require that changes in carbon intensity of energy lead the way. See TCF for the gory details and simple math explaining why this is so.

Maybe if you squint you can see a bit of an inflection point in the decarbonization curve about a decade ago. However, by 2022 the curve was back on trend.

The apocalypse crowd punches above their weight and the media love them, but they will never be taken seriously in policy settings.

How to tell if you are a neo-Malthusian? Do you view population and economic growth as levers to reduce emissions? If yes, welcome to the club.

In our debate last night, Koonin was on much stronger ground when he advanced arguments grounded in energy realism than when he purported to know with certainty how the climate and economy would evolve to 2100.

How to tell if you are an ecomodernist? Do you view improving energy intensity and carbon intensity as the only viable levers for deep decarbonization? If yes, welcome to the club.

The legacy media will be the last to acknowledge that the nature of energy and climate debates have moved beyond “alarmists and deniers,” as narratives grounded in science-as-politics are well established and get clicks.

The “last ton” means getting carbon dioxide emissions down to where emissions are balanced by sinks, so perhaps an ~80% reduction +/- from today. See Tom Wigley earlier this week.

Energy Realist. The developing economies responsible for the increases in emissions will not have achieved their economic development goals and reverted to zero emissions by 2050, though that might happen by 2100. Today, the developed world is attempting to achieve net zero using technologies which are "not ready for prime time" and might never be ready.

I am an energy realist. In today’s political climate I can accept the ecomodernist approach because society wants to do something and the approach of developing new technology and nuclear energy is something that might work. Actually we need new technology because the resources we depend on now are finite. As an energy realist, I would exclude any attempts to use wind and solar. They cannot work because energy storage is required and energy storage, on the scale necessary, needs to repeal the laws of physics first.