In 1983, Michael Barkun, today a professor emeritus at Syracuse University, wrote an incredible essay, presciently identifying the rise of a “New Apocalypticism” in American political discourse. Today I share some excerpts from that 40-year-old essay — Divided Apocalypse: Thinking About The End in Contemporary America — and connect them to today’s public discussions of climate change.

Barkun defined the “New Apocalypticism,” as follows;

The so-called "New Apocalypticism" is undeniably religious, rooted in the Protestant millenarian tradition. Religious apocalypticism is, however, not the only apocalypticism current in American society. A newer, more diffuse, but indisputably influential apocalypticism coexists with it. Secular rather than religious, this second variety grows out of a naturalistic world view, indebted to science and to social criticism rather than to theology. Many of its authors are academics, the works themselves directed at a lay audience of influential persons — government officials, business leaders, and journalists — presumed to have the power to intervene in order to avert planetary catastrophe.

Barkun observed that intellectuals were fulfilling a societal function previously served by religious leaders, even though these intellectuals did not always view science and religion to be compatible:

. . . however uninformed or unsympathetic these secular prophets may be concerning their religious counterparts, they clearly recognize the presence in their own work of religious motifs. Their predictions of "last things" generate the feelings of awe that have always surrounded eschatology, even if in this case the predictions often grow out of computer modelling rather than Biblical proof-texts.

For many, science has come to replace religion in its perceived ability to identify the root cause of our existential crisis and scientists have replaced religious leaders as holding the unique ability to offer guidance on how we must transform in order to stave off catastrophe:

Ironically, just as religious apocalyptic literature has begun to de-emphasize the natural world, the new secular literature has made it more prominent. By concentrating upon the capacity of human action to destabilize natural rhythms, the secular writers have made nature more important while acknowledging the potency of human act . . . The religionists' transformation of the world, to be accomplished in the Last Days, would now occur gradually as the consequence human intervention. This confident, redemptionist view of science carried the corollary of the necessity and desirability of human mastery over the natural world — precisely the sin most uniformly attacked in the secular apocalyptic literature of today. Where this mastery over nature was once viewed as the road to greater happiness and fulfillment, it now appears to be the route to doomsday.

For the secular millenarian, extreme events — floods, hurricanes, fires — are more than mere portents, they are evidence of our sins of the past and provide opportunities for redemption in the future, if only we listen, accept and change:

Where the religious view regards events as signs, the secular position is far more apt to view them as direct causes: the future will occur because of actions taken in the past and the present, but the future may be changed by making different present choices. At one level, this shifts causal efficacy from an external deity to human beings. At another level, by opening the possibility that The End might be averted by timely action, the change introduces a measure of indeterminacy, as opposed to the fundamentalist emphasis upon inevitability. The opportunity for preventive action makes the secular scenarios appear more hopeful, because, in principle, destructive actions by human beings might be prevented — intentional acts might be forestalled by pointing out their likely consequences, while human error might be reduced by more closely monitoring the conduct of those in positions of responsibility. Nonetheless, this approach can only hold out the hope of minimizing risks, which leaves some ineradicable possibility of danger, because evil, ignorant, or inadvertent behavior can never be eliminated.

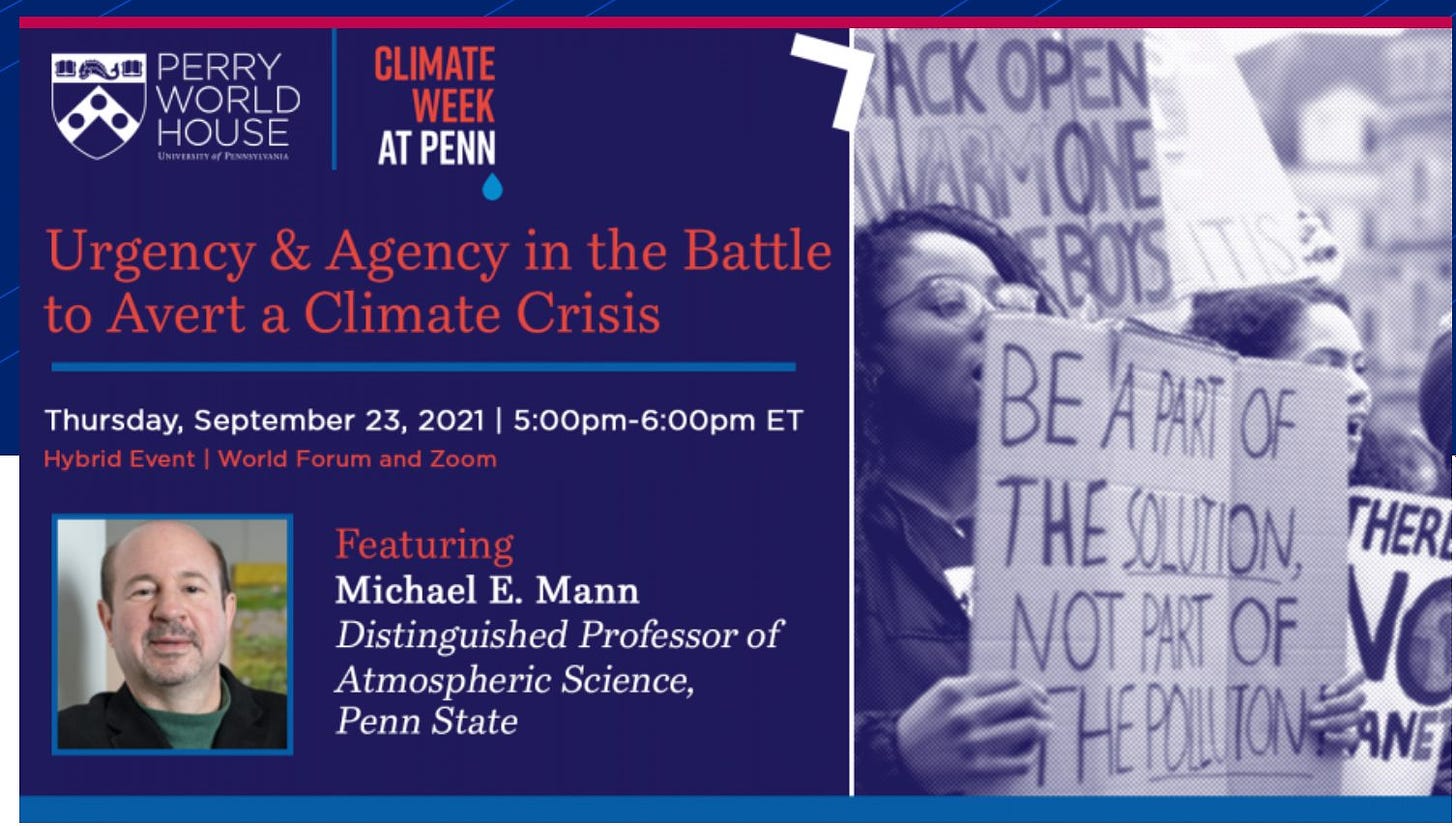

When we hear oft-quoted climate scientists warning that our calamitous times are the consequence of our misguided past actions and that the route to a different future is transformation — For instance, “urgency and agency” in the sloganeering of popular climate scientist Michael Mann, above. We can understand these dynamics as those of today’s priests of the secular apocalypse, explaining our predicament and offering the hope of salvation.

Barkun argues that secular apocalyptic worldviews are also compatible with a Manichean perspective on good and evil:

. . . secular apocalypticists tend to adopt two strategies. On the one hand, they may ascribe the suffering to the machinations of small but powerful groups, whose control of economic, military, or other resources permits them to place the fate of others in jeopardy. This view has the advantage of establishing a Manichean order, but it is, unfortunately, also a strategy that readily slides towards despair if the forces of good appear weak.

We’ve all heard the sermon — it is the fossil fuel companies, Republicans, the Koch Brothers, deniers and other shadowy forces who have conspired to thwart the climate movement for many decades. If only they could be defeated, transformation would occur and the apocalypse would be avoided.

Not surprisingly, the secular apocalypse is also interpreted as partly the consequence of ignorant or uncaring normal people, who have failed to heed the warnings of the experts. Despite the warnings, normal people continue to fly in planes, drive cars, eat hamburgers, use air conditioning and refuse to change:

On the other hand, world destruction may be viewed as the unintended consequence of human actions that are ill-informed, ill-timed, or inept. According to those who hold this view, the victims of world destruction are at least partially to blame for their fate, since had they behaved differently, they might have prevented it. The first position, the conspiratorial view, preserves the appearance of moral order by secularizing the Armageddon myth, in which good and evil contend, yet retains an element of indeterminacy not found in the religious version. The second position, ascribing inadequacies to the victims, attempts to reestablish moral order by implying that the suffering may not be wholly unmerited - the victims may somehow deserve their fate because they acted unwisely.

How might the contemporary New Apocalypticism evolve in the future? Barkun offers three possibilities:

One possibility, of course, is that either the religious or the secular apocalypticists are correct, and that history will indeed end within the lifetime of individuals now living.

We might indeed be in the latter stages of an existential climate crisis, fail to change and learn the end is nigh.

A second possibility, borne out in past instances of religious prediction, is that vague forecasts will give way to more precise predictions as expanding audiences seek the progressive reduction of ambiguity. Where this occurs the stage is set for prophetic disconfirmation, for a particular moment when a specific prediction is publicly discontinued, and the movement associated with it rapidly contracts to a hard-core of the most committed believers.

What happens when the world passes the 1.5 Celsius temperature target and the world does not end? Or then 2.0 C? On the other hand, there will always be sufficient numbers of extreme weather events across the planet to long sustain the idea that doom is just around the corner. Barkun explains that apocalyptic beliefs have been present in societies for centuries, and thus probably won’t be going away anytime soon.

A third possibility is that the number of believers may become so large that their very numbers and influence produce a fundamental change in the social order. The rise of Christianity during the late Roman Empire and the disillusionment of the Russian population immediately before the Russian Revolution are cases in point. Here, dire predictions can become, or can closely resemble, self-fulfilling prophesies.

This of course is the “all in” strategy of many climate activists — force the desired global transformation to happen and then take credit for the avoided Armageddon. I’ve argued that the global population crisis ended with a declaration of success with claims made that raising alarm saved billions from starvation — even though this view does not actually square with history. If we rapidly decarbonize, then the apocalypse will remain real, just unrealized — we already see this dynamic at play in discussions of the outdated RCP8.5 scenario.

Barkun’s 1983 essay is remarkable when read in the context of the 2023 climate movement. Climate change is of course real and important, but it is not (according to the IPCC) the apocalypse. The near-term future of climate policy will almost certainly be a struggle between pragmatism and the New Apocalypticism. How that turns out is anybody’s guess.

For those who have access here is the cite and link to Barkun’s remarkable essay:

Barkun, M. (1983). Divided apocalypse: Thinking about the end in contemporary America. Soundings, 257-280.

I welcome your comments. Please share and like, that helps get word out about THB, which provides data-rich and evidence-grounded analyses that you will not find anywhere else. Thanks to my subscribers! And if you are not a subscriber, please sign-up, join the community and the discussion. Have a great weekend.

All of this may be true, but I think the politicians who are driving this agenda have different motivations. This catastrophism allows them a pretext to centralize power, allocate resources to favored groups, and buy votes by providing relief to some constituents when their policies cause everyone to become poorer. It’s all very rational when the goal is to accumulate power and get re-elected.

Wonderful essay - thanks for sharing and including your insights.