The Global Population Crisis that Never Was

Apocalyptic visions of over-population have always been grounded more in politics than science

Thomas Malthus was a fan of pandemics. Writing in 1798 in his famous treatise on population growth, Malthus encouraged the spread of fatal diseases: “Instead of recommending cleanliness to the poor, we should encourage contrary habits.” He criticized “benevolent, but much mistaken men” who were seeking to eliminate fatal diseases, rather than see them as a way to naturally cull people from the earth.

These views has come to be known as Malthusianism. Here I’ll relate a little-known story of neo-Malthusianism — about how geopolitics, technological advances and scientific ambition came together to create and sustain a myth of avoided global famine in the 1960s and 1970s.

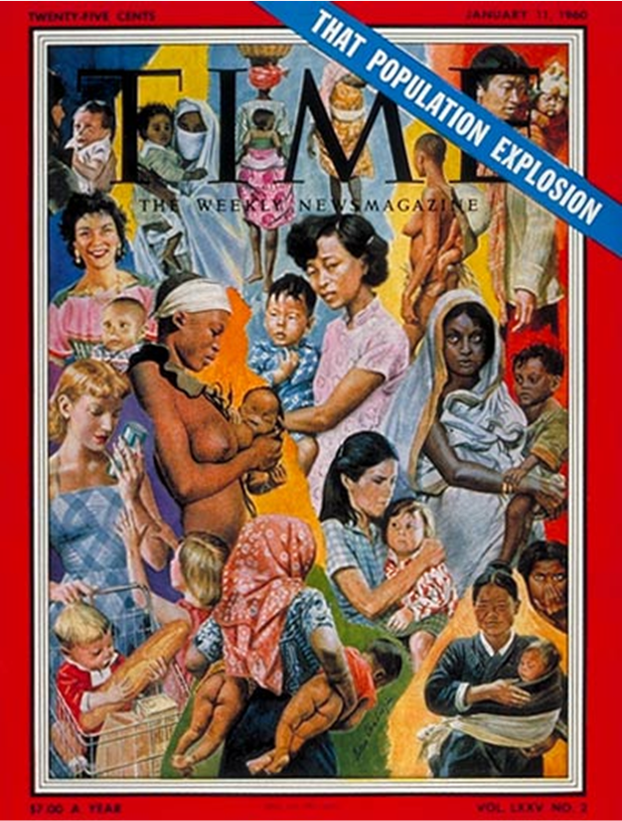

The myth, as is commonly told, tells the story of a mid-twentieth century world headed for disaster. There were too many people being born and not enough food being produced. This combination of forces would lead inexorably to famine, unchecked migration, conflict and other calamities. However, thanks to the inventiveness of Western scientists more food was produced, Armageddon was avoided, and the world did not experience a population crisis.

Almost every element of this myth is historically questionable. Evidence strongly suggests that there was in fact no population crisis. The fact that a global famine did not occur was not actually evidence of a successful intervention, but evidence of the fact that the crisis never existed in the first place.

In a 2019 paper, titled “From Green Revolution to Green Evolution: A Critique of the Political Myth of Averted Famine,” Björn-Ola Linnér and I make this argument in detail. Here I’ll share some key points.

Post-World War II U.S. foreign policy centered on containing the spread of communism. U.S. leaders viewed efforts to improve the material living conditions of people around the world as a key element of soft power in the Cold War. Meantime, domestic agricultural production had improved so much that farmers were experiencing economic strains due to depressed prices. Unhappy farmers were an electoral concern for U.S. politicians.

So Harry S Truman’s 1949 inauguration speech outlined a foreign aid program that would simultaneously demonstrate America’s benevolence and at the same time address domestic agricultural oversupply — Genius! By the 1960s, food aid was central to U.S. foreign policy. The “Food for Peace” program, established in 1954 under President Dwight Eisenhower, was seen as a key resource in helping to prevent the spread of communism into southeast Asia.

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson wanted to use the Food for Peace program to support India’s industrial development, by motivating famers to leave the countryside and move to cities. But Johnson faced opposition from Congress. So, as Nick Cullather writes in his excellent book, The Hungry World, “through the fall of 1965 [Johnson] developed the theme of a world food crisis brought on by runaway population growth.” The political justification for food aid shifted to concern about over-population, displacing Johnson’s unchanged Cold War motivations.

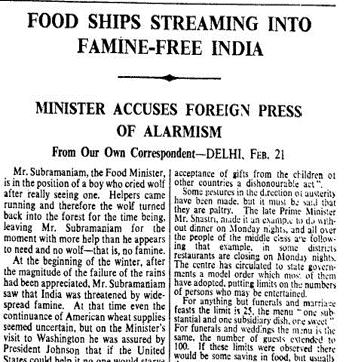

But there was one big problem. India was not at the time facing a famine. Of course, India was a country with many people living in poverty, but there was no incipient crisis. So in response to Johnson’s promotion of a growing famine, the Indian government wanted to avoid a possible domestic panic and responded that “there was no famine.” Even before the internet and ready communication across continents, the disagreement was a potential political problem for both President Johnson and for the Indian government.

So in March 1966, President Johnson and Indian Prime Minister Indira Ghandi met in Washington, D.C. to get their different stories straight. The US State Department explained that what emerged from their private discussions had to thread a narrow needle – “it shouldn’t be such as to frighten people in India, but on the other hand the need must be seen to be real in the United States.”

The Indian delegation noted that, “The situation in the United States is that to get a response, the need must be somewhat overplayed” and “the case should be presented as this being the year in which famine was averted.” The global climate seemingly played along, with a strong El Niño event of 1965-66 leading to rainfall deficits in parts of India and the first back-to-back failure of the Indian monsoon since 1904-1905.

Here we have an early and significant example of politicians playing fast-and-loose with evidence to advance their political objectives. Johnson and Ghandi’s subterfuge illustrates that challenges to scientific integrity at the highest levels of government are not a new phenomena.

Not only did Johnson and Ghandi get away with their ruse, but they found willing allies in important parts of the scientific community which had long adopted a Malthusian view of the world. Following Johnson and Ghandi’s summit, a symposium held at the U.S. National Academy of Sciences warned that, “the fate of all men will be the fate of India.”

Scientific mobilization was therefore needed to avert the looming crisis. For neo-Malthusians, whose work long pre-dated the 1960s, their moment had seemingly arrived.

India did not experience a massive famine, even with the monsoon failures of 1965-66. To be sure U.S. food aid was welcomed by many in India, but the main reason for the absence of widespread famine was that India produced more food and improved its distribution, well before modern varieties of crop staples had become widely utilized.

Even so, the famine myth had taken off. In 1970, upon receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, Norman Borlaug, the person most closely associated with the “Green Revolution” in agricultural productivity, warned of mythologizing:

Perhaps the term “Green Revolution”, as commonly used, is premature, too optimistic, or too broad in scope. Too often it seems to convey the impression of a general revolution in yields per hectare and in total production of all crops throughout vast areas comprising many countries. Sometimes it also implies that all farmers are uniformly benefited by the breakthrough in production. These implications both oversimplify and distort the facts.

Borlaug knew that reality was more complicated.

No matter. Myths have their own momentum. It wasn’t long after that Paul Ehrlich’s best-seller, The Population Bomb, amplified fears of over-population, again citing India as a frightening example of our common future based on a 1966 visit that he had made to Delhi:

The streets seemed alive with people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing, and screaming. People thrust their hands through the taxi window, begging. People defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people. . . . [S]ince that night, I’ve known the feel of overpopulation.

As Charles Mann observes, at the time, the “population of Paris was about 8 million. No matter how carefully one searches through archives, it is not easy to find expressions of alarm about how the Champs-Élysées was “alive with people.” Instead, Paris in 1966 was an emblem of elegance and sophistication.”

In 2018, Ehrlich told Mann that “the book’s main contribution was to make population control “acceptable” as “a topic to debate.”” Mann observes, “the book did far more than that. It gave a huge jolt to the nascent environmental movement and fueled an anti-population-growth crusade that led to human rights abuses around the world.” These are important issues for discussion in a future column.

Myths give meaning. They also have consequences. While it is increasingly understood that neo-Malthusianism often provides a thin veneer for racist, imperialist and misanthropic views, Malthusianism lives on in how we think and act. To paraphrase a quip made 30 years ago, Malthus has been buried many times, but anyone who has been buried so often cannot be entirely dead.

Read more: Pielke, R., & Linnér, B-O. 2019. From Green Revolution to Green Evolution: A Critique of the Political Myth of Averted Famine. Minerva, 57:265-291.