Does Climate Research have an Anti-Growth Problem?

A new paper suggests that the answer is "Yes"

A just-released paper in Nature Sustainability by Lewis C. King and colleagues reports the results of a poll of climate researchers across disciplines and across the world on their view of “green growth,” defined as:

“the desirability and feasibility of aligning environmental goals with continued economic expansion”

The authors contrast green growth with “degrowth” which they define as “a deliberate and equitable reduction in material consumption and economic activity in high-income countries” and “agrowth” which they define as “agnosticism” towards green growth.

The survey results indicate that a majority of climate researchers do not support green growth, with a greater overall number supporting degrowth. These numbers are wildly out-of-step with the views of the broader public. Among researchers from different disciplines and regions there are also large differences. It is interesting to note that despite the apparent support for degrowth, scenarios of degrowth have not made their way into the IPCC. All such scenarios project significant future economic growth — which is an interesting counterpoint to the expressed views of much of the community.

Let’s take a look at some numbers.

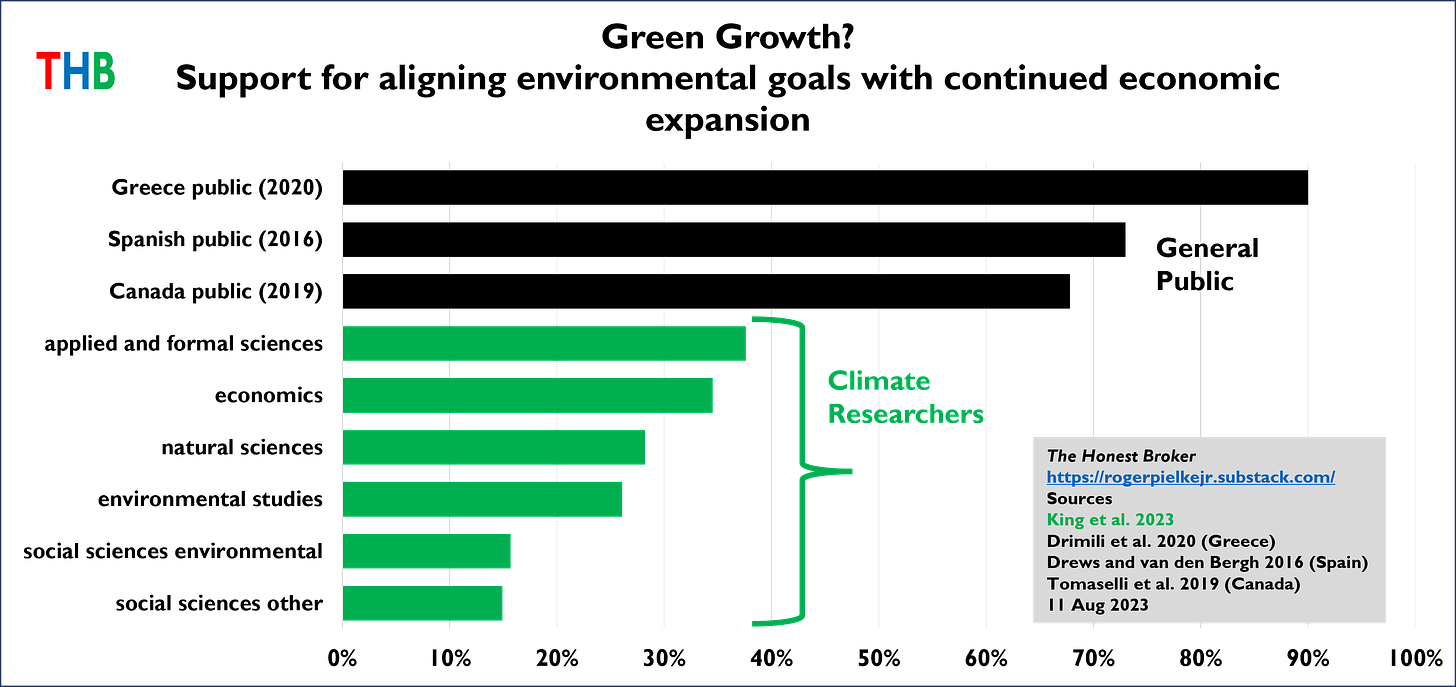

The figure below shows the results from King et al. for climate researchers who support green growth along with three studies in which the public was asked explicitly if they supported green growth — from Greece, Spain and Canada.

Note the large difference between climate researchers regardless of discipline (the green bars) and the general public in three wealthy countries (the black bars). In addition, there are large differences among different groups of researchers, with social scientists in particular showing very low support for green growth. No group of researchers reaches even 40% support for green growth.

To the extent that these views of climate researchers show up in the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), it would come as a surprise if the political agenda reflected in IPCC reports were to be out-of-step with the broader global public.

Indeed, the IPCC AR6 Working Group 2 (with a large representation of social scientists) endorsed the relevance of degrowth:

Consumption reductions, both voluntary and policy-induced, can have positive and double-dividend effects on efficiency as well as reductions in energy and materials use . . . a low-carbon transition in conjunction with social sustainability is possible, even without economic growth (Kallis et al. 2012; Jackson and Victor 2016; Stuart et al. 2017; Chapman and Fraser 2019; D’Alessandro et al. 2019; Gabriel and Bond 2019; Huang et al. 2019; Victor 2019). Such degrowth pathways may be crucial in combining technical feasibility of mitigation with social development goals (Hickel et al. 2021; Keyßer and Lenzen 2021).

King et al. also allow us to take a look at the views of climate researchers based upon where they are located, shown in the figure below.

Here we see that an overwhelming proportion of European researchers, in particular, do not support green growth, with researchers from North America and other OECD countries not far behind. Also of note, a majority of researchers from Brazil, Russia, India, China and other non-OECD countries do support green growth.

Only 7% of IPCC AR6 authors and review editors came from Least Developed Countries, those that are the poorest around the world. I’ll go out on a limb and suggest that 100% of these contributors are supporters of economic growth — green or any other color.

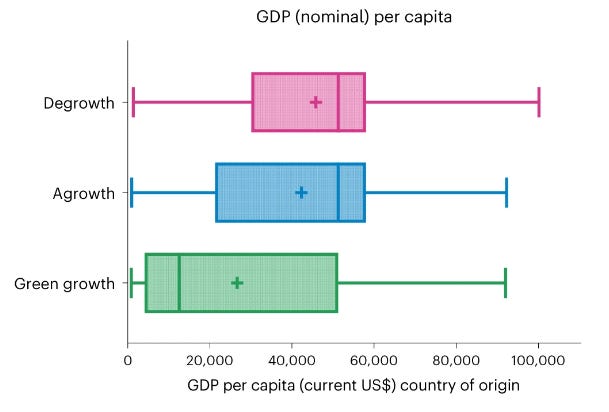

Indeed, King et al. show that degrowth support (and agnosticism) among climate researchers is centered among researchers from wealthy countries while support for green growth is centered among researchers from less wealthy countries. You can see this in their figure below.

It is easier to support degrowth when you are already rich.

It should come as no surprise that at times various reports and public-facing statements of the IPCC express skepticism of economic growth (the IPCC is of course not a monolith or a single entity, but it does have a public face). The maps below, via Carbon Brief, shows that all three reports of the IPCC AR6 were dominated by researchers from Europe and North America — regions together with less than 1 billion of the world’s 8 billion people, but with more than 50% of global GDP.

Climate researchers have an important role to play in providing advice to decision makers — I’ve long said that if the IPCC did not exist, we’d have to invent it. The climate research on which such advice is provided is also crucially important. At the same time, we must acknowledge that climate researchers, overall, are not representative of the countries that they come from much less the world’s citizens.

The center of gravity among climate researchers is wealthy, North American and European, and anti-green growth (and male also). Whether these characteristics are good or bad is not the point. Rather, asking a highly non-representative group to develop or advocate policies to be implemented among a much broader community — here the entire world and its constituent parts — is a recipe for delegitimization and loss of trust.

As the IPCC has shifted its role towards policy advice and advocacy, the organization risks losing legitimacy — not simply because because its participants hold views that are divergent from those held by the policy makers that it advises and the people they represent — but because those views are translated into proposals that favor the narrow interests and values of the center of gravity within the climate research community.

Scientific advice and assessment should not be about seeking to advance the interests of a small group of experts, but rather, about empowering the advancement of common interests, even when the interests of the broader public may diverge from those of experts.

The IPCC can better serve common interests by clarifying its advisory roles — e.g., science arbiter, political advocate, honest broker? — and then following through accordingly. An assessment body designed to answer empirical questions about climate (e.g., Have there been more hurricanes?) will look very different than one designed to provide policy options (e.g., What technologies can help us to decarbonize, consistent with our values?).

The dynamics described above — where experts hold different values and views than those of the general public — are of course not unique to climate. The tensions between expert advice and public decision making are central to many important issues today, and will only become more significant. It is thus crucial that the expert community do its part to maintain trust and legitimacy, because today we need experts more than ever.

Thanks for reading! It has been a busy week here at THB, so forgive me for clogging your in box. In my defense, there has been so much important stuff going that I want to share it while it is timely and before we are overcome by what comes next. And something surely will come next. Please like and share, and if you are not already a Subscriber, I invite you to join the THB community. Have a great weekend!

So many greenies fail to understand that man will overcome obstacles when they present themselves.

Early warning of obstacles in our life is important so we can be proactive. In support of this I provide the following brief summary of the Ehrlich -Simon wager:

In 1968, Ehrlich published The Population Bomb, which argued that mankind was facing a demographic catastrophe with the rate of population growth quickly outstripping growth in the supply of food and resources. Simon was highly skeptical of such claims, so proposed a wager, telling Ehrlich to select any raw material he wanted and select "any date more than a year away," and Simon would bet that the commodity's price on that date would be lower than what it was at the time of the wager.

Ehrlich and his colleagues picked five metals that they thought would undergo big price increases: chromium, copper, nickel, tin, and tungsten. Then, on paper, they bought $200 worth of each, for a total bet of $1,000, using the prices on September 29, 1980, as an index. They designated September 29, 1990, 10 years hence, as the payoff date. If the inflation-adjusted prices of the various metals rose in the interim, Simon would pay Ehrlich the combined difference. If the prices fell, Ehrlich et al. would pay Simon.

Between 1980 and 1990, the world's population grew by more than 800 million, the largest increase in one decade in all of history. But by September 1990, the price of each of Ehrlich's selected metals had fallen. Chromium, which had sold for $3.90 a pound in 1980, was down to $3.70 in 1990. Tin, which was $8.72 a pound in 1980, was down to $3.88 a decade later.[2]

As a result, in October 1990, Paul Ehrlich mailed Julian Simon a check for $576.07 to settle the wager in Simon's favor.

If one’s objective is human flourishing, de-growth is just at odds with that, plain and simple. Machiavelli’s classic 16th century work “The Prince”, talks about how an effective technique for an authoritarian ruler to maintain power is to convince the populace that there is a sever threat from which the ruler will protect them.

The climate catastrophe narrative is looking and smelling a lot like this. Remember, if it looks like a duck and smells like a duck, it’s a duck.