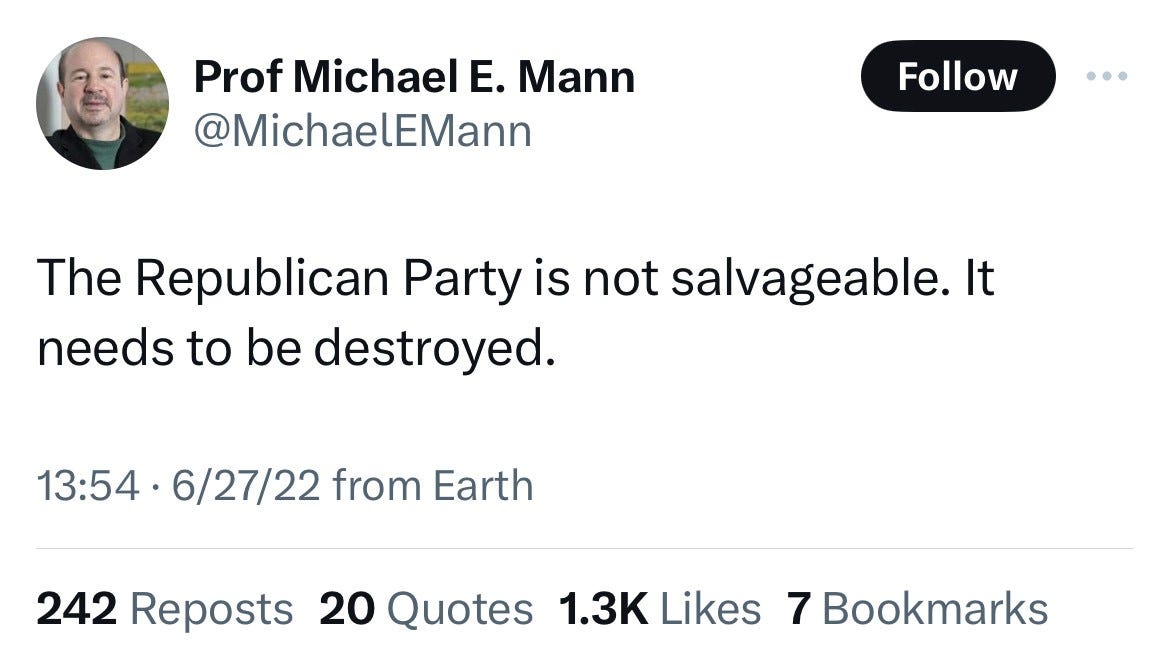

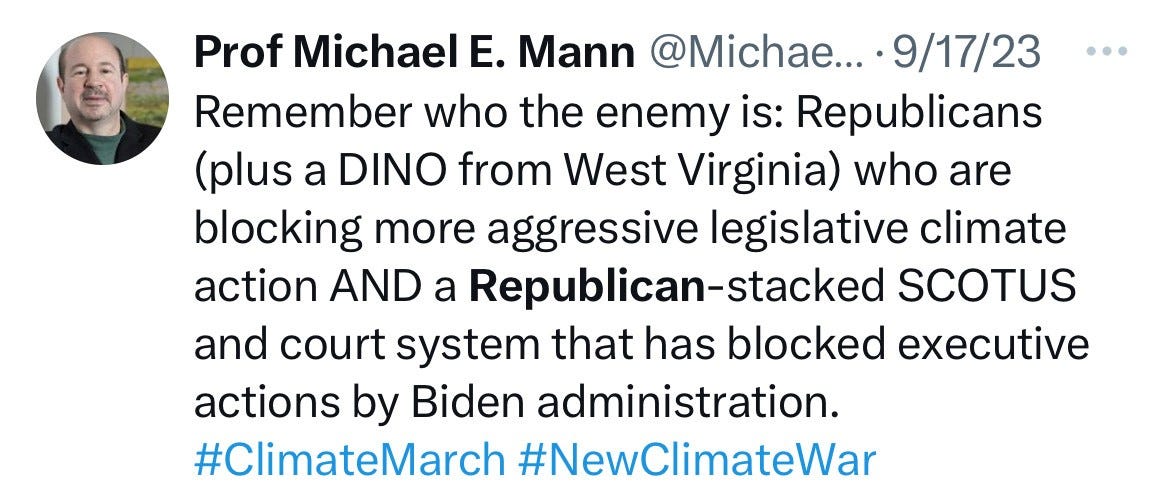

Remember who the enemy is: Republicans

Michael E. Mann, climate scientist, September 2023

The quote above comes from a recent Tweet1 by Michael Mann, the climate scientist who is arguably the most visible and influential influencer in the climate science community. Mann boasts more than 200,000 Twitter followers, is the go-to source for climate reporters on all-things climate, and was the inspiration for Leonardo DiCaprio’s portrayal of a heroic climate scientist in the movie, Don’t Look Up.

Mann is also a fierce political partisan who is quite vocal in his utter disdain for Republicans and unwavering endorsement of Democrats. He has also not been shy in his effort to police scientific discourse. In short, Mann is without a doubt the most influential and powerful climate science influencer on the planet. He is the Taylor Swift of climate science.

Does Mann’s style of “science communication” offer a template for how scientists ought to engage with their peers and broader society?

Some think so — in climate science, many have followed Mann’s lead and adopted a pugilistic and partisan approach to public engagement. Climate science is not unique. The popular medical researcher Peter Hotez of Baylor University associates “anti-science” with Republicans and “science” with Democrats. Similarly, scientists who have rejected the notion of a research-related incident as the origin of COVID-19 have chosen to characterize that theory in explicitly partisan terms. It is not just in the United States either — last month Nature chose to weigh in on the Argentinean presidential election.

Scientists are players in big time politics! That’s great, right?

Maybe not. An overtly partisan approach to public engagement may be pathological, compromising public trust and confidence, and making the practice of science itself much more political.

Last month, Pew reported that among Americans:

When asked how well climate scientists understand whether climate change is happening, 52% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say climate scientists understand this very well. In comparison, 51% of Republicans and Republican leaners say climate scientists understand this not too or not at all well.

Of course the average American does not have the expertise to evaluate understandings held by climate scientists, so the poll reflects confidence or trust in climate scientists. The large partisan split reported by Pew is not unique to climate or to Americans. Even with the partisan split a surprising number of Democrats report lower levels of confidence in climate scientists.

Why is there such a partisan split?

The glib answer of course is that the split reflects something wrong with people on the political right. After all, if the overwhelming majority of scientists are on the political left, that surely must tell us who the enemy is, as Mann reminds us. A current reporter for The Washington Post even wrote a book called The Republican Brain explaining a genetic basis for Republicans’ inability to appreciate science or reality. An “us versus them” Manichean framing is seductive and enduring.

From this perspective, hyper-partisanship is a feature, not a flaw, and we all should be working to destroy the Republican Party.

An irony here, and it is a deep irony, is that the turn to partisanship among science influencers ignores a substantial body of empirical research and real-world experience that indicates that the politicizing of science by scientists quickly turns pathological for science and society alike. The consequences include an overall loss of trust in institutions of science which is replaced with determinations of trust based on identity.

In other words, instead of bringing science more fully into politics, pathological politicization brings politics more fully into science. The public and policy makers are not fools — if we experts choose to make science more political, they too will respond politically. What did we expect would happen?

Let’s look at some evidence.

In a paper published earlier this year, Kaiping Chen, of the University of Wisconsin, and colleagues asked whether online science influencers like Michael Mann play a role in political polarization related to science. Chen looked at social media posts of 108 “science influencers” and found that “science influencers may focus on building online communities with ingroup solidarity to defend against outgroups over engaging with diverse audiences.”

In plain English, they found that science influencers emphasize an us versus them framing in their social media engagement. Us refers to the “in group” — people like us, with the right values and beliefs. Them refers to the “out group’ — those people, the deniers and disbelievers with the wrong beliefs.

In the Chen dataset, among the influencers with the highest proportion of in-group Tweets were Boris Johnson, Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump — Right behind them? Michael Mann.2

Chen and colleagues conclude:

It is important to conceptualize scientific skepticism and rejection as not only a cognitive process, but a result of social dynamics and intergroup conflict

I’ll put it less academically — The extreme partisanship of leading science influencers may well be contributing to increasing political polarization among the public related to science and a concomitant loss of public trust in science and scientists, especially among those who have less in common with scientists.3

That scientists have politics is neither new nor interesting. I have my politics and you have yours. The bigger issue here is not a single climate science influencer, but why it is that the climate science community, and other areas of science as well, have decided to elevate and celebrate fierce political partisans.

A 2022 study of public trust in science in Norway found that citizens have lower trust in scientists who are in fields that are perceived to be politicized, including economics and climate science:

[T]rust in climate scientists and economists is lower than trust in less politicized natural scientists because the former fields are politicized, while the latter are not. Politicization strengthens ideological conflicts between citizens' ideology and research produced by climate scientists and economists, which leads to lower trust in these groups of scientists.

Research consistently shows that when scientists or scientific institutions adopt partisan positions, it leads to a loss of trust among those who views are not endorsed. For instance, a recent study by Floyd Jiuyun Zhang of Stanford University of the effects of Nature’s 2020 endorsement of Joe Biden found that the endorsement reduced trust among Trump supporters:

In a preregistered large-sample controlled experiment, I randomly assigned participants to receive information about the endorsement of Joe Biden by the scientific journal Nature during the COVID-19 pandemic. The endorsement message caused large reductions in stated trust in Nature among Trump supporters. This distrust lowered the demand for COVID-related information provided by Nature, as evidenced by substantially reduced requests for Nature articles on vaccine efficacy when offered.

Did the editorial staff of Nature really believe that their endorsement of Biden was so important that it was worth damaging trust in the journal as an institution in the midst of a global pandemic?

The actions of climate science influencers goes beyond inflammatory partisan statements issued over social media or endorsement of parties and candidates. It has been well documented that climate science influencers also seek to police online debate, what is published in the peer reviewed literature and even who should be allowed to speak on climate at universities.4 Much of this is a reflection of partisan politics taking root within institutions of science.

Fanning the flames of polarization is a choice. Research indicates that social media dynamics encourage the formation of echo chambers and epistemic bubbles. Scientific institutions should work explicitly to counter pathological politicization rather than let it flourish. At stake is science’s longstanding position as being among the most trusted institutions across society.

Why does the scientific community act in ways counter to its own interests and risk compromising the standing of scientific institutions in broader society?

I don’t claim to fully understand the answer, but here are some alternative explanations for why leaders in the climate community have embraced extreme partisans:

Polarization is a good thing. Perhaps the climate community is so like-minded in its political orientation that they actually want a political battle with those who have different political views. It is in fact us-versus-them — bring it on.

The right must be eliminated. An even stronger orientation is a (nonsensical) belief among some scientists that the political right can be vanquished in the “climate war.” This seems to be a view of the extremely-online, but not so much normal scientists.

Disbelief in polarization research. Perhaps science influencers disbelieve research on polarization and how their behavior may be contributing to pathological politicization. Polarization deniers?

Bullied and fearful. Maybe science influencers — and climate influencers in particular — have simply staged a hostile takeover of the community, including its leading institutions. The silent majority of not-so-partisan folks are simply powerless to push back.

Unawareness. Perhaps the broader scientific community is simply unaware of the consequences of hyper-partisanship among science influencers, and view them as loud but harmless. If so, that would suggest a need for more training in science and technology studies!

Careerism. A final hypothesis is that hyper-partisanship among science influencers has proven to be extremely rewarding for professional careers — fame and fortune readily follow. In the absence of strong science instructions, the incentives for seeking personal gain likely outweighs any considerations of broader consequences for science or politics.

As with all of science, climate science and policy is too important to be reduced to a “battlefield” for partisan conflict. While partisanship is seductive and carries with it individual rewards, it can also be pathological and damaging to both science and policy.

Thanks for reading! I welcome your comments. NOTE: I do not want any comments made of a personal nature here about Mann. Yes, he is a polarizing figure, by design. My use of him as an example in this post is about his behaviors and the consequences of those types of behaviors, not about him personally. Any derogatory, demeaning or insulting comments will be removed — just don’t. I do welcome discussion of polarization and its consequences. Most importantly, how can we collectively do better?

In the Chen et al. data, Mann is in first place for “in-group” posts on Facebook.

In this recent post I explained that American’s loss of trust in science was pretty much across the board, except for those who share identity characteristics of the majority of the scientific community — e.g., educational credentials, wealthy, white, male.

Oh the stories I can tell.

Alas, it is the fools and fanatics who are so adamantly certain and the wise who are full of doubts.

The classic scientific method is cautious, humble, careful to point out the limits and flaws of conclusions drawn. "Post-normal science" is taking its place in all too many circumstances. "Post-normal science" is not science at all in the classic sense, but sorting the evidence to support one's preferred policy options, to serve "the greater good". In the global warming question, one of the earliest practitioners was Stephen Schneider, who advocated striking a balance between hiding doubts and "telling scary stories" to galvanize the public.

Once this "post-normal science" takes hold, it inevitably leads second-rate personalities into "noble cause corruption". The next step is Leninist crushing of dissent of the sort you personally, Roger, have experienced. There is nothing so pernicious to a true search for truth. But such attacks are standard operating procedure these days for so many of the eco-zealots and Social Justice warriors seizing today's headlines.

Of the reasons Roger listed for politicization, I would rank carreerism at the top followed closely by fear, which is strongly linked to career concerns. I would add that it's not just a matter of overt politicization but a politicization favoring Democrats. The reason for that, I believe, is that scientific research tends to be funded by governments and government funding tends to flow easier under Democratic administrations as opposed to small government oriented Republicans.