The Public is OK, It's Us Scientists Who are the Problem

The uncomfortable conclusions of a new survey of public trust in science

Tomorrow in Washington, D.C. I will be participating on a panel discussion at the American Enterprise Institute titled, Science and Social Trust: Politics, Religion, and the Crisis of Expertise (with details at that link for how you can join us in person or online). We will be discussing a report on public trust in science just released by AEI’ Survey Center on American Life — America’s Crisis of Confidence: Rising Mistrust, Conspiracies, and Vaccine Hesitancy After COVID-19.

In this post I will preview and develop some of the arguments that I’ll be making on the panel, focused on “Social Trust and Scientific Expertise” – where I am thrilled to be alongside Professor Kimberly Michelle Rios and Professor Maya Goldenberg (whose excellent book I reviewed here).

The new AEI survey reinforces evidence showing that even as trust and confidence1 in science among the American public overall remains relatively high in a time of broad public distrust of institutions, science too has experienced a decline in public trust.

AEI explains:

America is experiencing a crisis of expertise—one that has worsened since the COVID-19 pandemic and shows little sign of abating. A nationally representative survey conducted by the Survey Center on American Life finds that a growing number of Americans are distrustful of scientific and medical experts.

Typically, the idea of a crisis of public trust in science is quickly accompanied by a diagnosis (from us scientists, of course) that identifies the crisis as a failure of the public, e.g., in being easily duped by monied interests or evil politicians, and simply not smart enough to know enough to come to the proper views. This of course is a version of the old deficit model which posits that the public has a knowledge deficit, which if corrected through science communication and education would then lead to changed policy and political preferences — as well as increasing overall public trust in science.

Here I wish to overview an alternative argument that I’ve been making for almost two decades — trust in science (including scientists and scientific institutions) is placed at risk when leading scientists and institutions become politically active in ways that diverge from the values and preferences of the broader public. The new AEI survey provides some data that supports the idea that loss of trust in science may indeed have a causal element related to the politics and advocacy of scientists.2

Democrats whose highest formal education is a high school degree express confidence in science more like typical Republicans than they do like college+ educated Democrats.

Importantly, AEI finds one “exceptional” group when it comes to trust in science — highly educated, white, secular Democrats:

Americans who express the highest degree of confidence in scientific and medical experts—secular white Democrats with a bachelor’s degree or higher—appear to be relatively exceptional. In fact, well-educated white liberals are outliers from the mean, having considerably greater confidence than other Americans do. The overall high levels of trust among Democrats, as compared to Republicans, could therefore reflect the predominance of well-educated whites in the Democratic Party.

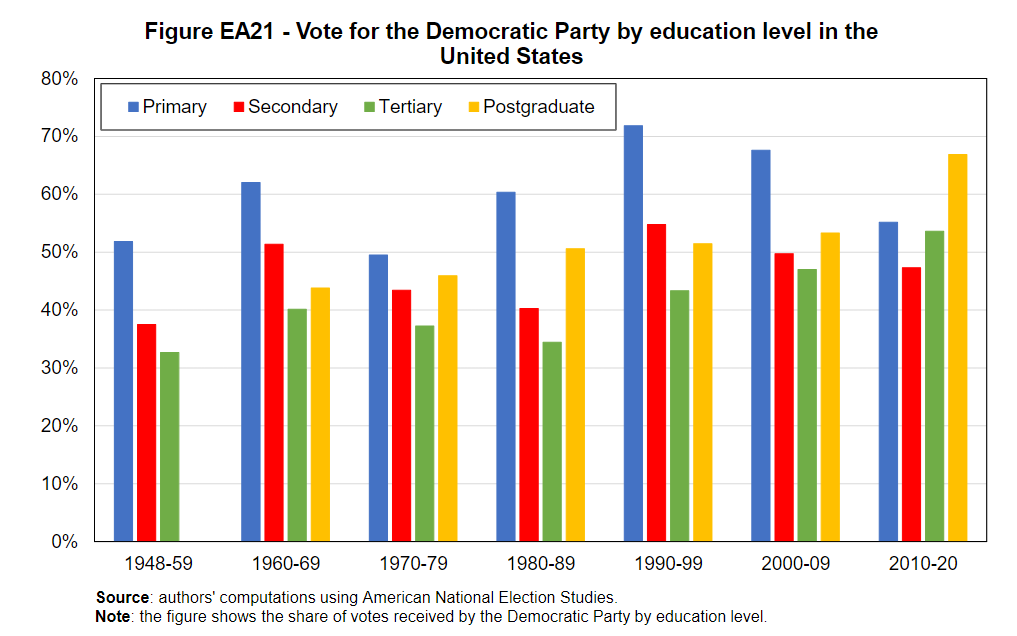

Research by Thomas Piketty and colleagues shows that over the past 40 years, the greater the formal education level among U.S. voters, the higher the proportional vote for Democrats — a trend that is not unique to the U.S. (on a left-right spectrum) and which has been underway for many decades. You can see the U.S. case in their figure below — pay close attention to the green and yellow bars since the 1980s.

Since scientists are by profession among those with the most formal education, they are obviously among those whose voting behavior is most skewed towards Democrats. That U.S. scientists have political views on the left, even the far left, will not come as a surprise to anyone.

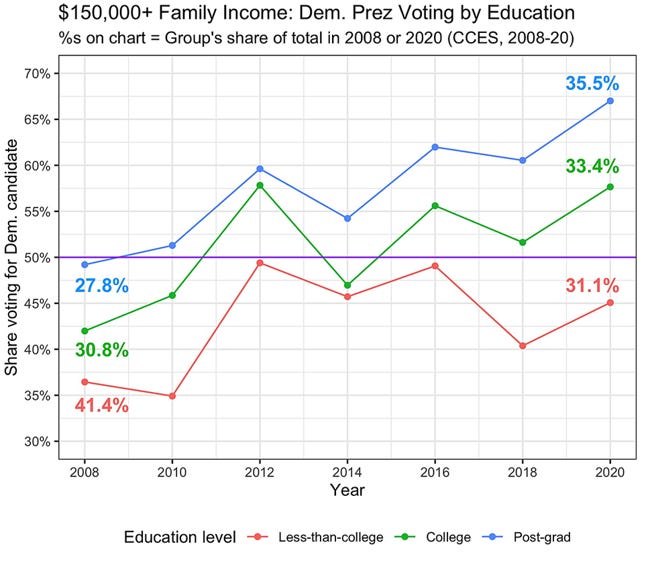

Since formal education is correlated with income, it will also not come as a surprise that as the highly educated have tended more towards the political left, so too have the wealthy. As Zacher 2023 documents:

“Affluent Americans used to vote for Republican politicians. Now they vote for Democrats.”

You can see that trend clearly in Zacher’s figure below, with the strongest swing among those with >$150,000 in income also having post-graduate credentials.

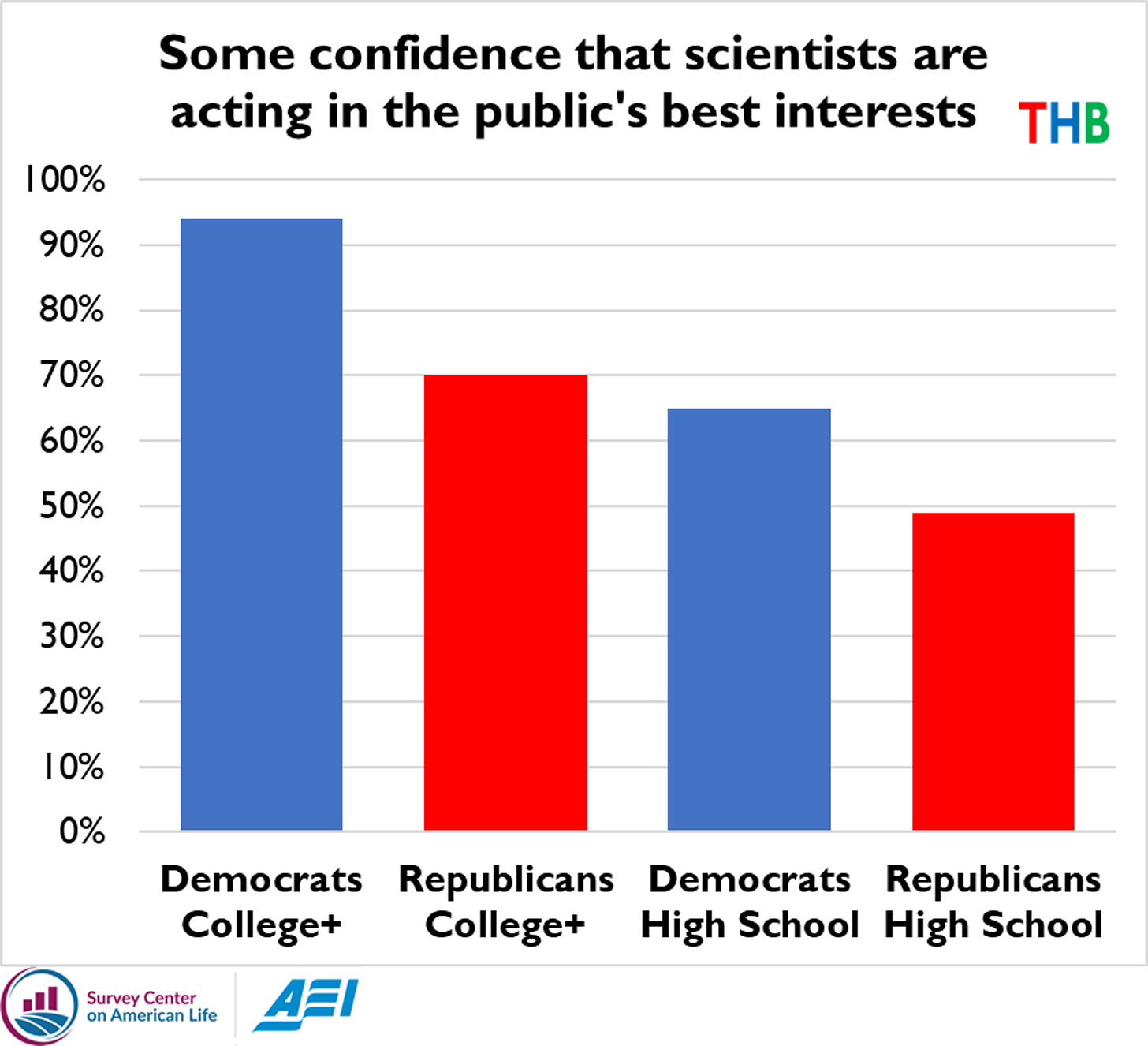

Let’s now return to the new AEI survey. The figure below shows the well-known partisan split between Republicans and Democrats in their expressed confidence in science.

But let’s look a little closer and consider educational attainment in addition to party affiliation.

These data show that Democrats whose highest formal education is a high school degree express confidence in science more like typical Republicans than they do like college+ educated Democrats. Put another way — with respect to confidence in science, college educated Democrats and Republicans are more alike than are college-educated and high school-educated Democrats. That the educational divide is larger than the partisan divide will be a surprise to many, I am sure.

Two more figures help to complete the picture.

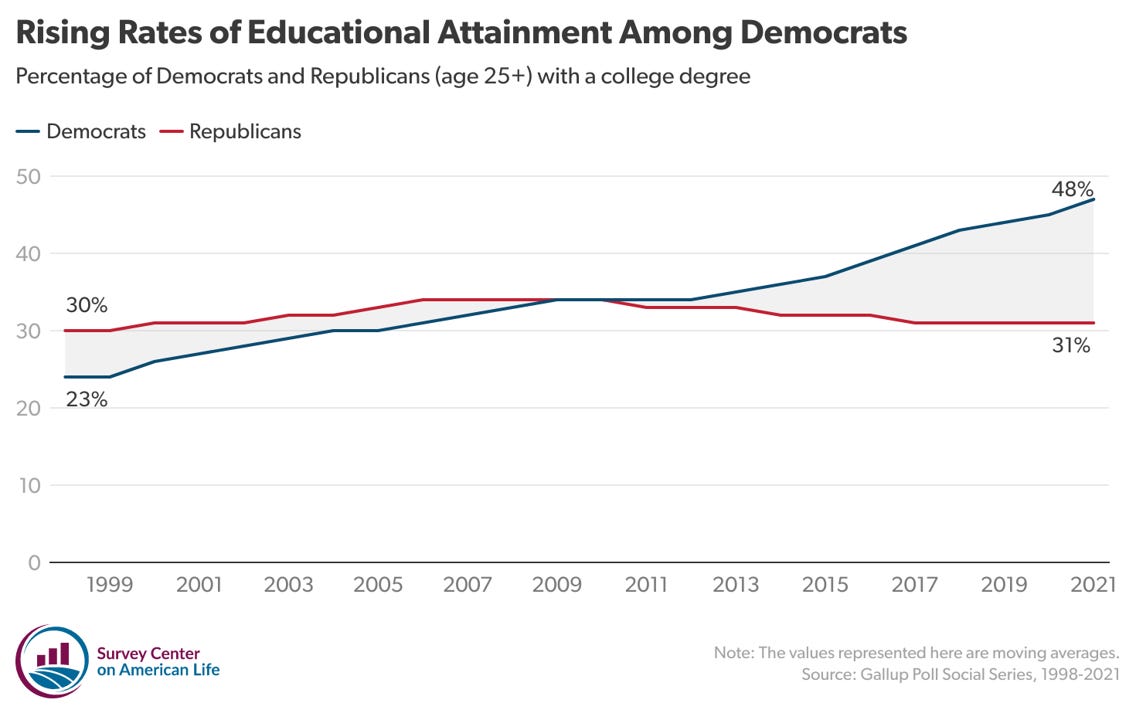

First, the figure below from a 2022 AEI Survey Center on American Life shows that Democrats have increasingly become the party of the college educated. However, as recently as 2021 the college-educated still did not comprise a majority of Democrats.

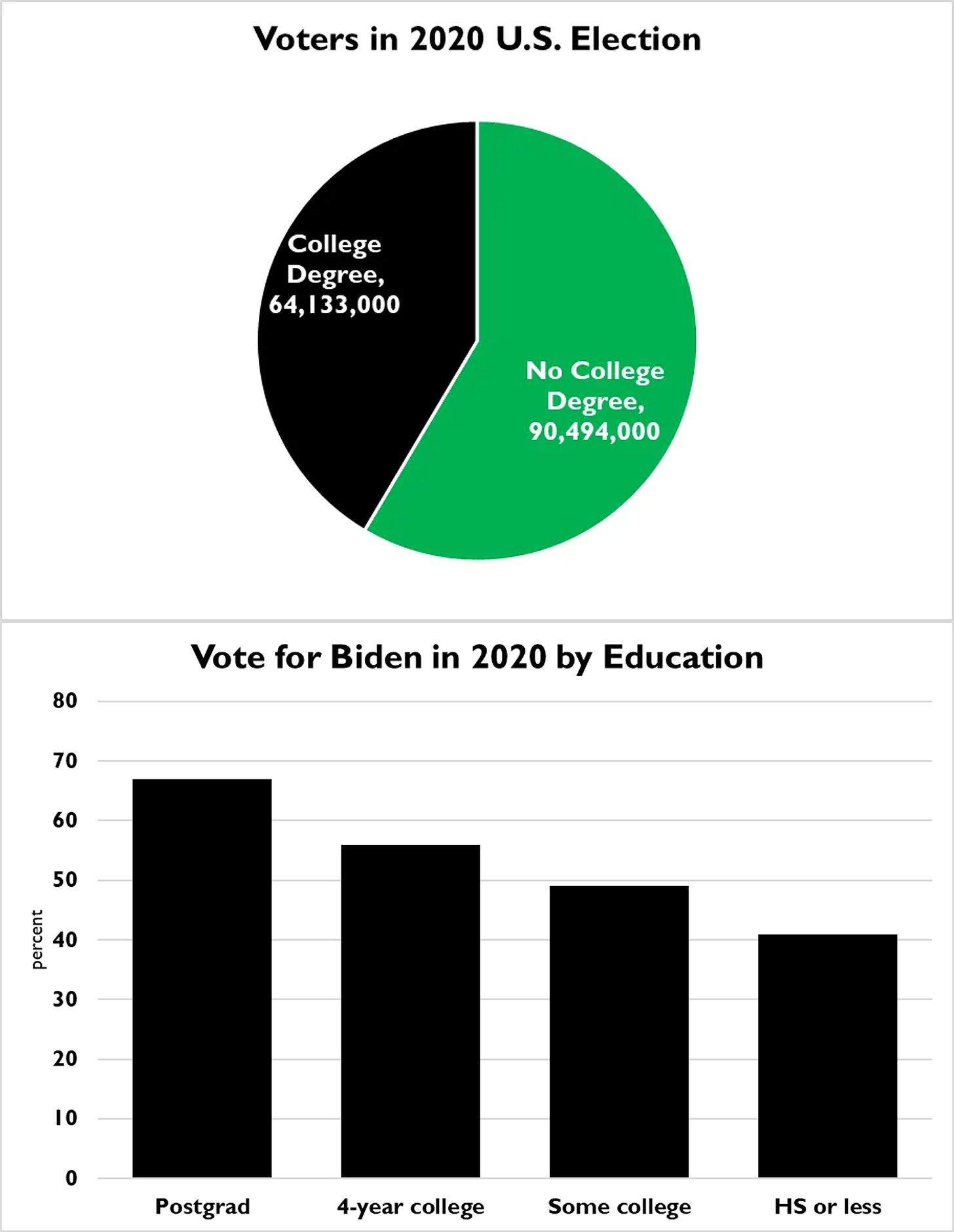

Second, the figures below show voters in the 2020 U.S. presidential election by educational attainment. The figures show that Joe Biden’s victory depended upon winning majorities of the college+ educated while losing among those without a college degree. This was a precarious strategy as voters without a college degree outnumbered those with by almost 3 to 2.

Let’s review:

Those with greater educational attainment have increasingly voted Democratic;

The wealthy (which overlaps with those with greater educational attainment) also have increasingly voted Democratic;

However, neither a majority of Americans nor a majority of Democrats are highly educated or relatively wealthy;

But scientists are both highly educated and relatively wealthy;

All of these dynamics are more extreme at higher levels of education (notably at the Ph.D. level).

In short, scientists overall are different than most people in American society. (Scientists overall are also disproportionately white, male and secular.)

Consequentially, as a group scientists and the institutions that they lead typically have chosen to express values and politics that are broadly inconsistent with those of normal Americans. The consequences are predictable — Consider the steep drop in trust in science among Hispanic and Black Americans found in the new AEI survey:

[F]rom January 2019 to May 2023, the percentage of Hispanic Americans expressing a great deal or some confidence in scientists dropped from 82 percent to 61 percent. The pattern is similar for black Americans—from 85 percent to 69 percent over that same period. Generally, non-white Democrats are half as likely as white Democrats to express a great deal of confidence in scientists.

Here is where things may get a bit uncomfortable for the scientific community — to the extent that the community, or more accurately, its influencers and leaders seek to pursue the community’s narrow interests over the broader common interest values expressed by the public, the public will overall increasingly lose confidence in the scientific community, while those who most closely share the scientific community’s narrow interests will express increasing confidence in science.

This is not rocket science.

Elsewhere I have documented examples of prominent members of the scientific community cheerleading for Democrats, expressing disdain and disrespect for Republicans and government more generally, denigrating the general public, the less educated and opposing policy goals that the general public thinks are pretty important, like economic growth.

More than a decade ago Dan Sarewitz warned us that the scientific community faced a fork in the road:

The US scientific community must decide if it wants to be a Democratic interest group or if it wants to reassert its value as an independent national asset.

Sarewitz warned of consequences:

The more… the science community, is seen to line up behind one party, the less claim it will have to special status in informing difficult political and social decisions. Public regard for scientists remains particularly high, and for politicians, particularly low. Blurring the boundaries between these groups is not likely to redound to the benefit of politicians, but to the detriment of scientists.

Scientists and the institutions that they lead probably cannot do much to arrest the overall decline in public support for institutions, but it is well within our scope and responsibility to address the partisan, educational, religious, economic and racial divides in how science is trusted among the broader public.

In fact, addressing the crisis of confidence in public trust in science should be the community’s top priority. It is that important.

Thanks for reading! I welcome your comments, critique and suggestions. Please share this post with friends, colleagues and family. Honest brokering is a group effort. I’d appreciate clicks on the little heary above and reStacking or sharing via your favorite social media. All Subscribers are welcome, and if you are already a subscriber, please consider an upgrade to support the work of THB.

I’ll use the words trust and confidence interchangeably in this post, however, there are important distinctions to be made between them. See, e.g., Luhmann 2000, Kattumana 2022, Vallier 2019.

I am using the broad term scientists here, but obviously those who are most important for public views of science are those who are most prominently in public view —we might call this subset of scientists something like “science influencers” — Anthony Fauci and Michael Mann are examples. Leading scientific organizations and their spokespeople also fit into this subset — including leading journals like Science and Nature, national academies, professional associations and so on.

Highly educated (PhD) white guy here (UK), formerly left-wing, formerly technocratic. Now cured of both and filled with regret that I ever thought my views had any greater worth than those with lesser educational attainment or with conservative or populist attitudes.

Recent irritations with scientists:

1: Academic support (or silence) for utterly unscientific gender ideology; moral cowardice when colleagues who spoke out against it were cancelled or lost their careers.

2: Silence in the face of obvious failures in everything to do with pandemic handling, from NPIs to vaccine harms. 'Follow/Trust THE science' - I don't recall the chorus of scientists publicly challenging this nonsense.

3: Silence in the face of overblown climate alarmism. 'THE science is settled' - as in (2)

You are right - politicisation plays a major role here. If you had more right-wing scientists, then you would have far less of 1-3.

You might argue that my choice of topics is unfair; scientists have families to feed, they need to keep their jobs, and they can't challenge the system or risk their research funding. This does not inspire confidence that we should trust what scientists say; it just maybe partially mitigates their culpability.

In general, I think it is WAY too late for the 'scientific community' to just 'burnish your images' a bit to reclaim public trust, and I say this from the point of view of a research scientist at a world-class antennas and radar research laboratory. It is clear to me that reputable science can no longer be conducted in any field that doesn't have a tight correlation between experimental results and fundamental physics and math; any field, such as climate 'science', 'gender science', 'social science', psychology, etc. that CAN be corrupted has already BEEN corrupted. No scientific journals, except those where math and experimental results can be easily replicated are in the least bit trustable anymore - they are just politically correct yellow journalism now.

Convince me that I'm wrong; convince me that you could write a paper that isn't fully in line with the current 'climate narrative' and have it published in ANY peer-reviewed journal.