The Politics and Policy of a National Climate Emergency Declaration

If climate and energy policy matter, then here are the three questions to ask instead

Yesterday, Bloomberg reported that the Biden Administration is once again considering declaring a national “climate emergency,” explaining that such a declaration could be used to “halt [fossil fuel] exports, drilling.” Today, I have extensively updated a 2022 piece I wrote on such a declaration. The consideration of such a declaration reveals a stark divergence between election-year politics and effective climate and energy policies. Rather than asking whether a “climate emergency” declaration makes sense, I recommend the three other questions to ask instead. Comments welcomed!

“A significant feature of American government during the last fifteen years is the expansion of governmental activity on the basis of emergency.” That is the opening line in a 1949 academic paper on “Emergencies and the Presidency.” The role of the president in declaring a state of emergency to achieve policy goals has been a policy issue that dates back at least to President Abraham Lincoln.

Today, President Biden is once again being called upon by his supporters to declare a national emergency on climate change. Rather than argue for or against it, in this post I’m going to explain the history of such declarations, what recent experience says about their effectiveness in policy, and suggest the three questions we should be asking instead.

A national emergency declaration may be a political end, but it is also supposed to be a policy means — a mechanism intended to achieve certain outcomes in the national interest. Apart from the politics of using an emergency declaration to signal affinity with certain political interests, below I recommend the policy questions that we should be asking instead.

In 1866, in the case of Ex parte Milligan, the Supreme Court argued that the Constitution allowed sufficient room for the government to deal with existential threats, and that the invocation of additional authority by the president beyond that already granted by the Constitution was unnecessary and a bad idea:

“The Constitution of the United States is a law for rulers and people, equally in war and in peace, and covers with the shield of its protection all classes of men, at all times and under all circumstances. No doctrine involving more pernicious consequences was ever invented by the wit of man than that any of its provisions can be suspended during any of the great exigencies of government. Such a doctrine leads directly to anarchy or despotism, but the theory of necessity on which it is based is false, for the government, within the Constitution, has all the powers granted to it which are necessary to preserve its existence”

Even so, in the century that followed this ruling the invocation of emergency powers by the president expanded dramatically, especially under the administration of Franklin Roosevelt and then during and after World War 2.

In the 1970s, Congress viewed the presidential assertions of emergency and the corresponding expansion of presidential powers to be problematic from the standpoint of the balance of powers between branches of government. The Senate observed in a 1973 report that the country was then under four declared emergencies that were being used to implement 470 different administrative statutes.1

The Senate expressed concern that these emergencies justified a wide range of extraordinary and problematic presidential authority:

Under the powers delegated by these statutes, the President may: seize property; organize and control the means of production; seize commodities; assign military forces abroad; institute martial law; seize and control all transportation and communication; regulate the operation of private enterprise; restrict travel; and, in a plethora of particular ways, control the lives of all American citizens.

Congress sought to limit these seeming unchecked executive powers via the National Emergencies Act of 1976 which was signed into law by President Gerald Ford. The legislation established more formal legal guidelines for the use of emergency powers by the president and created a mechanism for Congress to force the end of a particular declaration, in an effort to rein in the expansion of executive authority.

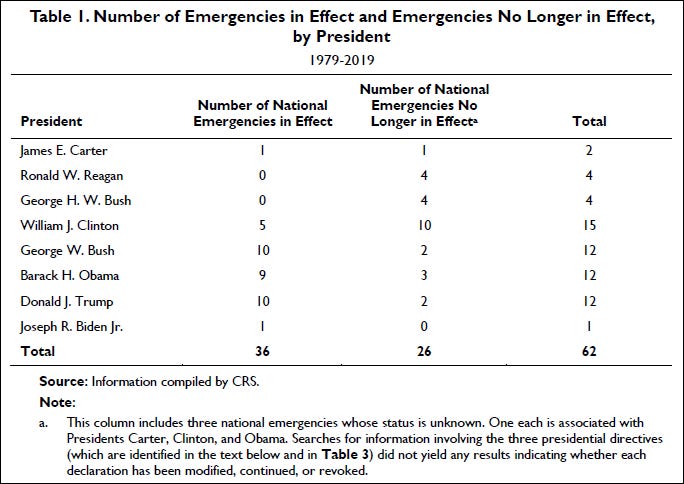

Since that time the U.S. president has declared 69 emergencies, and since the Clinton Administration the practice has become fairly common, as you can see in the table below from the Congressional Research Service. Currently, the U.S. has 42 active national emergencies in effect, the oldest dating to the Carter Administration and the Iran hostage crisis. Emergency declarations continue remain in effect that were declared by all presidents since Carter except Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, meaning that if a current president declares a national emergency, then it is likely to be around for a while.

Since President Carter, Democratic presidents have declared 37 national emergencies and Republican presidents declared 32. The Clinton Administration declared the highest number of emergencies, with 15, but the GW Bush, Trump, and Biden Administrations issued more per year in office. To date, President Biden has declared eight national emergencies.

Recent experience is instructive. In February, 2019 the Trump Administration declared an emergency declaration on the southern border in order to “build the wall” in the absence of Congressional support. Congress, under the provisions of the 1976 Emergencies Act immediately sought to terminate Trump’s emergency declaration. However, a 1983 Supreme Court judgment meant that to do so, Congressional action would require the president’s signature, rather than simply reflect an expedited majority opinion of the House and Senate. That meant Congress would have to override a veto if the president disagreed.

Soon after, Congress passed legislation terminating President Trump’s emergency at the southern border, and then unsurprisingly President Trump vetoed the legislation. The subsequent congressional effort to override the veto fell well short in the House, achieving only 248 of the 290 votes necessary. President Biden terminated the emergency at the southern border on his first day in office in January 20, 2020.

What does this brief history tell us about the prospects for President Biden to declare a nation emergency on climate? I suggest three things.

First, President Biden is well within his authority to declare a national emergency on climate. Since he took office, on many occasions President Biden has called climate change an “existential threat” to humanity, the world and to the nation.

Whether or not climate change actually represents such an existential threat is a separate issue to whether or not President Biden has the authority to declare a national climate emergency. On the latter the answer is clearly yes. But remember, if President Biden can declare a national emergency on issues he thinks Congress is failing to act on, so too can the next president. The abuse of national emergency declaration authority by both parties to expand presidential powers is not in my view a good idea — That is why the U.S. Constitution established checks and balances.2

Second, such a declaration could in principle expand the powers available to the president to take executive actions that his administration views as useful in responding to the declared climate emergency. The key phrase here is “in principle.”

Trump’s border emergency declaration did not actually result in the building of a border wall and President Biden ended the emergency on the first day of his presidency. We should expect that any climate emergency will remain in place only as long as a Democrat is president, as Congress appears unlikely to achieve a veto-proof majority for either party anytime soon. The president already has a wide range of administrative authority to take executive action on climate, and it is questionable what added policy benefit an emergency declaration provides in the absence of Congressional legislation.

Third, those who see climate as the most important political issue (small in numbers but influential in the Democratic party) will cheer, while those adamantly opposed to any climate action (small in numbers but influential in the Republication party) will have an issue to rally around. A climate emergency declaration is much more about politics than policy.

But just for a moment, let us take the policy issues seriously. Remember that from a policy standpoint, a national emergency is a means to achieve policy ends. Here are the three questions we should be asking about climate and energy policy rather than whether declaring a national climate emergency makes sense:

Is it in the U.S. national interest to immediately limit, reduce, or halt:

Exports of fossil fuels?

The production of fossil fuels?

The consumption of fossil fuels?

If the answer to any of these three questions is “yes,”3 then the next question is whether the declaration of a national climate emergency is the most effective mechanism for achieving these goals. If the answer to any of them is “no,” then we should be discussing other policy means to achieve long-term, deep decarbonization while securing energy security and sustaining economic growth.

If the Biden Administration truly wishes to quickly dial back U.S. fossil fuel exports, production, and consumption, then U.S. policy would be much better served by the administration openly stating as much. Of course, given the actions of the Biden Administration to date — with exports and production booming — I doubt that they have any such interests.

As it now typical in climate discussions, the current debate over whether or not President Biden should declare a climate emergency is just more red meat for political partisans in an election year. However, for those who care about climate and energy policies and their effectiveness, a divergence of politics and policy should be a concern, as that is a recipe for dysfunction.

Comments, discussion, critique and questions are all welcome! Partisan red meat (on either side), not so much. THB is reader supported by your subscriptions, including those who are able to contribute to support my work and this forum. Thanks to everyone in the THB community, it is a group effort!

Four. How quaint. As you’ll read below, today it is 42.

Amending the National Emergencies Act of 1976 to allow for a congressional override of a presidentially-declared national energy with a simple majority would go a long way towards limiting the abuse of emergency powers by the president.

For the record, I do not think the answer to any of these three question is “yes” and at the same time I also believe that pragmatic policies supporting accelerated decarbonization make excellent sense.

Well done!

I was a little disappointed in your belief "that pragmatic policies supporting accelerated accelerated decarbonization make excellent sense." (I'm assuming the double "accelerated" is your mind stuttering.) If we're going to do it, then let's have a solid plan. California certainly thinks it has accelerated decarbonization, but it's been at the cost of ever-more-frequent brownouts (and if Diablo Canyon actually closes in 2030, I predict blackouts).

The problem is two-fold - skyrocketing demand, and the problems with increasing capacity.

• Demand. Over the last 50 years, California's demand for electricity has increased almost linearly. However, mandates forcing the electrification of transportation and the blooming of data centers across the state and country make it easy to project a spike in demand (perhaps doubling) in the next decade. At the same time, fossil plants (natural gas currently provides about a third of CA's electricity) are being forced to retire. San Onofre nuclear station was closed in 2013; at the time it provided about 1/6 of CA's electric needs. CA's high electric rates also partially reflect the state's need to purchase power on spot markets - about 25% of its electricity is imported (mostly from the Pacific NW, but some from Mexico). Diablo Canyon provides about 10% of CA's electricity, but is now scheduled to close in 2030.

• Increasing capacity. There are really only two options – more renewables (the favored choice of the enviro cult) or more nuclear. CA's brownouts has brought attention to an interesting problem with renewables. In olden times (around Y2K) if you had enough power to cover peak demand (around 3-5 pm), you had enough power to cover the entire day. Starting in 2020, the increase in renewables and the overall increase in demand meant the system operators had enough power to cover peak demand, but if the weather didn't cooperate then there wasn't enough electricity to meet the demand of people coming home, plugging in their cars, turning on their ACs, after the peak. Hence the brownouts that started in 2020 and have occurred sporadically since.

If we increase the fraction of renewables we just increase the system's vulnerability to hot, cloudy, windless days. Further, few people seem to be concerned about the land needed for renewables. Diablo Canyon's power production site takes up about 0.01 sq mi. Using the best estimates I can find, that translates into about 28 sq mi for a solar replacement; and, of course, this doesn't take into account solar's intermittency. It would take about 4X that much to actually match Diablo Canyon's (or that of a fossil fuel plant) output. And then we would need batteries to store the solar-generated power.

Batteries have their own problems. They're expensive - really expensive: the 680 MW Nova Power Bank will cost over $1 B, and it would take at least three of these for our notional renewable replacement for Diablo Canyon. And it will only provide that power for a period of four hours - if you need more, forget it.

In principle, nuclear is the answer. No CO2, and a minuscule amount of waste. However, as I know all too well from the $9 B fiasco with the failed Sumner plant expansion here in SC, these projects are fiscally and legally vulnerable. I love the concept of the small nukes, but they won't be around until the '30's.

So. I'm left with my original question to add to your three: What do you mean by "acceleration?"

Compared to what? On what timetable? With what money?

“In searching for a new enemy to unite us, we came up with the idea that pollution, the threat of global warming, water shortages, famine and the like would fit the bill… All these dangers are caused by human intervention… The real enemy then, is humanity itself.” (Club of Rome, The First Global Revolution, 1991)

A Climate Emergency would be a blatant power grab, as was Covid, but I don't see much in the way of resistance arising from the masses. During Covid I did not lock down, surely did not vaccinate, and only rarely wore a mask if some store insisted. I never used hand sanitizer and never once stood on one of those damned 6-feet stickers. I did not like the attention my behavior brought my way, but so be it, as a free human being my mask (when forced to wear it -slit horizontally so I could breathe) said it all: SHEEP. We are not free unless we claim our freedom by our behavior.