A National Climate Emergency is the Latest Distraction from Achieving Effective Climate Policy

Partisan red meat does little to improve federal climate policies

“A significant feature of American government during the last fifteen years is the expansion of governmental activity on the basis of emergency.” That is the opening line in a 1949 academic paper on “Emergencies and the Presidency.” The role of the president in declaring a state of emergency to achieve policy goals has been a policy issue that dates at least to President Abraham Lincoln.

Today, President Biden is being called upon by his supporters to declare a national emergency on climate change. Rather than argue for or against it, in this post I’m going to explain why the decision to declare such an emergency is more about the symbolism of climate politics, rather than a serious effort to advance federal climate policy.

Whether or not President Biden declares such an emergency — and I suspect he will — U.S. climate policy will look much the same after a declaration as it does right now.

In 1866 the Supreme Court argued that the Constitution allowed sufficient room for dealing with existential threats, and that the invocation of additional authority by the president was unnecessary and a bad idea:

“The Constitution of the United States is a law for rulers and people, equally in war and in peace, and covers with the shield of its protection all classes of men, at all times and under all circumstances. No doctrine involving more pernicious consequences was ever invented by the wit of man than that any of its provisions can be suspended during any of the great exigencies of government. Such a doctrine leads directly to anarchy or despotism, but the theory of necessity on which it is based is false, for the government, within the Constitution, has all the powers granted to it which are necessary to preserve its existence”

Even so, the invocation of emergency powers by the president expanded dramatically over the next century, especially under the administration of Franklin Roosevelt and then during and after World War 2. In the 1970s, Congress viewed the presidential assertions of emergency and the corresponding expansion of presidential powers to be problematic. The Senate observed in a 1973 report that the country was then under four declared emergencies that were being used to implement 470 different administrative statutes.

The Senate expressed concern that these emergencies justified a wide range of extraordinary presidential authority:

Under the powers delegated by these statutes, the President may: seize property; organize and control the means of production; seize commodities; assign military forces abroad; institute martial law; seize and control all transportation and communication; regulate the operation of private enterprise; restrict travel; and, in a plethora of particular ways, control the lives of all American citizens.

Congress sought to limit these seeming unchecked executive powers via the National Emergencies Act of 1976 which was signed into law by President Gerald Ford. The legislation established more formal legal guidelines for the use of emergency powers by the president and created a mechanism for Congress to end the use of such powers.

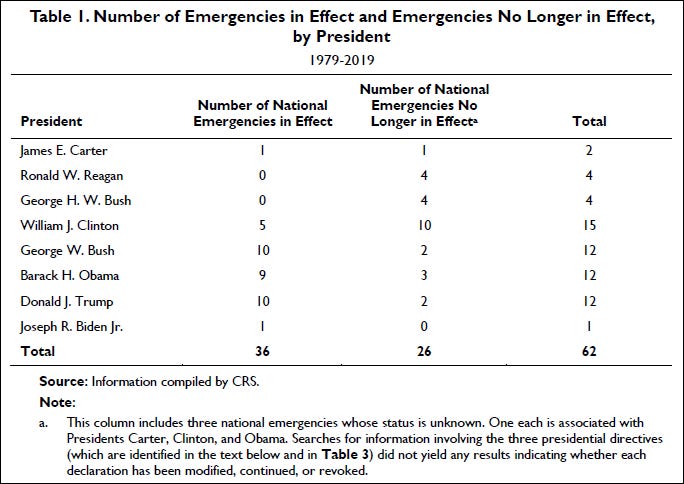

Since that time the president has declared 62 emergencies, and since the Clinton Administration the practice has become fairly common, as you can see in the table below. The Trump administration had the highest rate of emergencies, declaring a new emergency one every 4 months through his presidency. In the first 19 months of his administration, President Biden has so far declared only one emergency – last month suspending tariffs on solar cell and module imports from Asia -- the lowest rate since George H. W. Bush.

President Trump’s experiences are instructive. His frustration with his perception of a lack of sufficient Congressional support for funding his proposed border wall led to his February, 2019 issuance of an emergency declaration on the southern border. Congress, under the provisions of the 1976 Emergencies Act immediately sought to terminate the emergency declared at the southern border. However, a 1983 Supreme Court judgment meant that to do so, Congressional action would require the president’s signature, rather than simply reflect an expedited majority opinion of the House and Senate. That meant Congress would have to override a veto if the president disagreed.

In 2019, Congress passed legislation terminating President Trump’s emergency at the southern border, and then unsurprisingly President Trump vetoed the legislation. The subsequent congressional effort to override the veto fell well short in the House, achieving only 248 of the 290 votes necessary. President Biden terminated the emergency at the southern border on his first day in office in January 20, 2020.

What does this brief history tell us about the prospects for President Biden to declare a nation emergency on climate? I suggest three things.

First, President Biden is well within his authority to declare a national emergency on climate. Since he took office, on many occasions President Biden has called climate change an “existential threat” to humanity, the world and to the nation. Whether or not climate change actually represents such an existential threat is a separate issue to whether or not President Biden has the authority to declare a national climate emergency. On the latter the answer is clearly yes. But remember, if President Biden can declare a national emergency on issues he thinks Congress is failing to act on, so too can the next president. The abuse of emergencies to expand presidential powers is not in my view generally a good idea — that is why the U.S. Constitution established checks and balances.

Second, such a declaration could in principle expand the powers available to the president to take executive actions that his administration views as useful in responding to the declared climate emergency. Here the recent experiences of the Trump Administration at its proposed border wall are instructive. Trump’s emergency declaration did not actually result in the building of a border wall and President Biden ended the emergency on the first day of his presidency. We should expect that any such emergency will remain in place only as long as a Democrat is president, as Congress appears unlikely to achieve 2/3 majority (required to override a veto) for either party anytime soon. The president already has a wide range of administrative authority to take executive action on climate, it is questionable what added policy benefit an emergency declaration provides in the absence of Congressional legislation.

Third, any such emergency declaration is likely to be symbolic and more than anything else, reflective of the utter dysfunctionality of the legislative branch when it comes to climate. Those who see climate as the most important political issue (small in numbers but influential in the Democratic party) will cheer, while those adamantly opposed to climate action (small in numbers but influential in the Republication party) will have an issue to rally around. This is much more about politics than policy.

As it now typical in the U.S. debate over federal climate policy, the current debate over whether or not President Biden should declare a climate emergency is red meat for political partisans. No one should be under the illusion that if a climate emergency declaration is declared, or it is not, that it will make any real policy difference in the rates of U.S. decarbonization.

Sustained progress, over many years and decades, will come from Congressional legislation that is incrementally improved over time. If you think that is too hard to accomplish, then you are also concluding that accelerated U.S. climate action at the federal is also too difficult. Because that is what it will take.

Paying subscribers to The Honest Broker receive subscriber-only posts, regular pointers to recommended readings, occasional direct emails with PDFs of my books and paywalled writings and the opportunity to participate in conversations on the site. I am also looking for additional ways to add value to those who see fit to support my work.

There are three subscription models:

1. The annual subscription: $80 annually

2. The standard monthly subscription: $8 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

3. Founders club: $500 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who have the ability or interest to support my work at a higher level.

Worse than distraction really. It gives a deeply flawed signal that this might make a difference when what is needed is urgent work on two very different fronts : reducing the vulnerability emergencies that abound at community scale while pursuing energy transformations that will unfold on the scale of many decades. The Brennan Center has done a heap of work laying out the structural and Constitutional issues. I explored all of this here: https://revkin.bulletin.com/it-s-essential-to-act-on-climate-emergencies-unfolding-on-a-heating-flooding-fiery-planet-but-a-mistake-for-biden-to-declare-one

It would be fun to see how Biden's people spin the reasons for the emergency.