Going All In With Peak Fossil Fuels by 2030

The International Energy Agency bets its reputation on an aggressive prediction

Earlier this week the International Energy Agency (IEA), headquartered in Paris and overseen by the OECD, issued a bold prediction in its 2023 World Energy Outlook (emphasis added):

The combination of growing momentum behind clean energy technologies and structural economic shifts around the world has major implications for fossil fuels, with peaks in global demand for coal, oil and natural gas all visible this decade – the first time this has happened in a WEO scenario based on today’s policy settings. In this scenario, the share of fossil fuels in global energy supply, which has been stuck for decades at around 80%, declines to 73% by 2030, with global energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions peaking by 2025.

Some found the prediction objectionable. For instance, upon release of the report the Premier of Alberta, Canada said the IEA had become politicized and was engaging in political advocacy:

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith is calling one of the world's premier energy research institutions "no longer credible'' after it released a report saying fossil fuel demand is likely to peak this decade.

Smith says the International Energy Agency no longer does analysis, it points to outcomes it wants and outlines paths to get there.

She is not alone. Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman said last month:

“They’ve moved from being a forecaster and assessors of market to one for political advocacy. That’s their choice.”

Similarly, Omar Farouk Ibrahimar, secretary general of the African Petroleum Producers’ Organization said:

“We know for sure that IEA will say everything it can say in order to scare the world from investing in fossil fuels”

Conflict over the IEA’s latest World Energy Outlook matters because the IEA, created in the 1970s to focus on oil, has evolved to serve as one of the world’s preeminent institutions providing global energy analyses to global decision makers.

As Christian Downie of the the Australian National University has written:

[T]he World Energy Outlook generally [is] considered to be one of the most authoritative global energy publications. In part this reflects that over time the IEA has become the world's repository for energy statistics, perhaps rivalled only by the US Energy Information Administration, and its energy scenarios are regularly used as a reference point for policymakers in IEA and non-IEA member states alike.

We might dismiss the criticisms of the IEA as coming from fossil fuel producers. Of course they would not much appreciate hearing that their fossil fuel resources — oil, natural gas and coal — are going to see peak consumption by the end of the decade.

On the other hand, if the fossil fuel producers are correct in their accusations — despite their interests — that the IEA has become focused more on energy advocacy than energy analyses, that would indeed be problematic.

To triangulate, I looked what the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) had to say on the issue of peak fossil fuels in its latest International Energy Outlook, released earlier this month, and compared its baseline projections to those of the IEA.

It is not hard to conclude that the IEA is taking a big risk with its reputation.

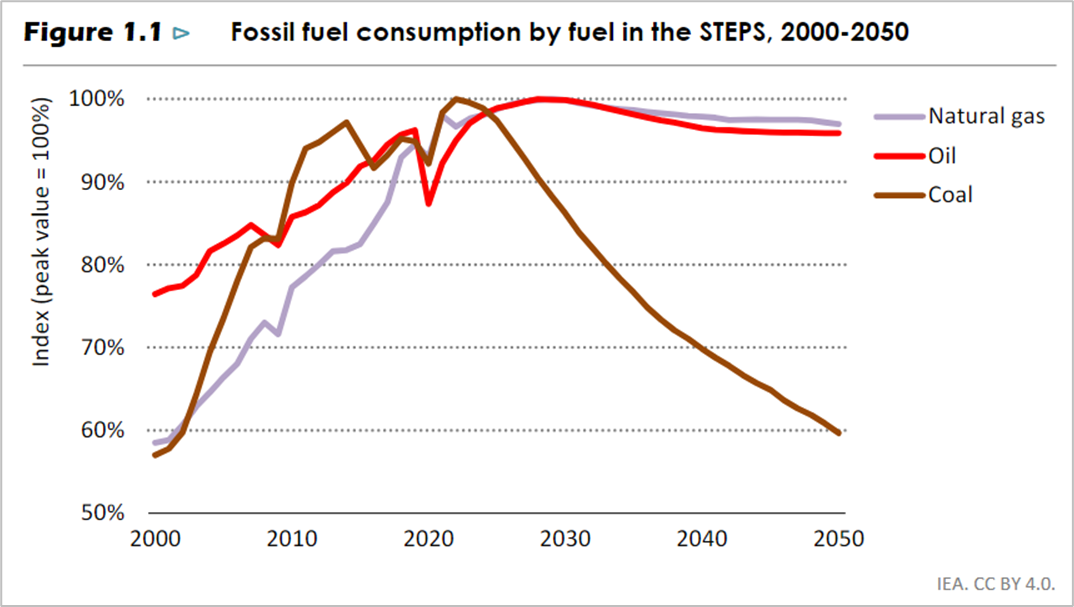

I started with the figure below from the IEA WEO 2023, which shows fossil fuel consumption for oil, natural gas and coal to 2050 under the IEA STEPS scenario, which can be understood as a stated policies baseline. The figure is indexed to the year of peak consumption for each fuel, and you can see that it shows a peak and decline for all three fuels by 2030 — with coal showing the most dramatic decline, and oil and natural gas looking more like a gradually declining plateau.

In order to compare the U.S. EIA projections to those in the figure above, I downloaded the EIA IEO 2023 reference scenario projections for each fuel and graphed them using the same indexing approach and color scheme that you see above. I then truncated the IEA figure so that it begins in 2025, and placed the two figures side-by-side. You can see the apples-to-apples result below.

Two things immediately stand out for me:

First, in its reference scenario the EIA foresees no peak in any of the fossil fuels before 2050. Coal increases the least, but still by about 5% over 2025.

Second, the differences between IEA and EIA are stark, especially so for coal. IEA sees a 40% decline by 2050 and EIA see an increase of about 5%.

There are a few nuances worth highlighting. The IEA has said explicitly that the peak in fossil fuels is based on “today’s policy settings alone.” That means that unless today’s policies are rolled back, we should expect to see these three peaks by 2030. IEA has indeed issued a prediction that requires no new policy adoption.

In contrast, the EIA scenario is a reference scenario created in the expectation that there will be additional energy policy action in the future to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Thus, the EIA reference scenario should be viewed as an upper bound on consumption — unless climate policies go into reverse — and in actuality fossil fuel consumption may undershoot its reference.1

The IEA has made a significant bet on peak fossil fuels and its reputation hangs in the balance. Here are the implications:

If the peak occurs by 2030, the IEA will be celebrated as going out on a limb and being correct, solidifying its position as the preeminent international body for energy system analyses.

If the peak does not occur by 2030, fossil fuel interests will say we-told-you-so and legitimate questions will then be asked about the politicization of the IEA’s analyses. The world needs more fair-minded science arbiters and honest brokers, as it has plenty of energy policy cheerleaders.

In either case, IEA’s issuance of the peak-fossil fuel forecast has created strong incentives for the organization to act as an advocate, because of the two possible outcomes above. Rooting for your own forecast is not a good situation to be in for a science advisory body — it is also the reason why we think it a bad idea to let referees bet on the games that they are officiating.

More generally, the issuance of a forecast by IEA contradicts everything we have learned about the perils of energy system forecasting. As Vaclav Smil has written:

With rare exceptions, medium- and long-range forecasts become largely worthless in a matter of years, and often a few months after their publication.

That is why we employ scenarios as possibilities and plausiblities, and not as predictions.

Debate over the IEA’s peak fossil fuel prediction will no doubt continue. But we will not have to wait very long to see how it turns out. Watch this space.

Thanks for reading, commenting, liking, sharing and subscribing! Have a great weekend.

Policies going into reverse are unlikely. However it is not impossible — Just yesterday Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced a temporary walk-back of some climate policies. File that under the iron law of climate policy.

"It is not hard to conclude that the IEA is taking a big risk with its reputation".

As if.

Show me one person or institution that has gotten called out or suffered any reputational damage for making outlandish nonsensical predictions? There are websites dedicated to cataloging failed climate/energy predictions, updated daily.

How about Paul Ehrlich, that guy has no credibility at all, does he?

Oh wait, no, he still gets interviewed and quoted as the rock star he is to all these corrupt institutions and people.

As long as they are supporting the narrative there are no consequences.

As someone who has been an adult long enough to remember Black Monday in 1987, the first Gulf War, etc it is evident that today's widely cited (by news media) scientific organizations no longer have the rational forecasting of the future as their purpose but rather cheerleading and advocating for an outcome. It's embarrassing to witness but only because I'm old enough to recognize a huckster when I see one. Over the last decade at least, I have had many arguments with otherwise intelligent people over diverse topics in which it becomes clear that the opposing argument doesn't recognize what IS but rather what they WANT as a baseline. With reality dispensed with early on, there really isn't anything impossible to believe and posit and scream about. That is of course a useless position when arguing the reality of a situation, but a lack of reason seems to not be a stumbling block to vapid ideas. It's pretty obvious that government funded institutions have a stake in what reality ought to look like, so why not nudge it a bit when the natural world doesn't act the way these folks believe it should. After all, it's their bread and butter, they are captive to a belief, and it's not their money at stake. Let them eat cake. This incidentally exactly captures what has taken place with the MRNA vaccines the government forced on people on threat of expulsion from public life and work.

Good luck to a nation captive to irrational beliefs. Quickly things get totalitarian when they don't go to plan in a control economy and in this case a controlled scientific community.