Global Existential Risks

A first look at a new U.S. government assessment on the most significant risks facing humanity

In 2022, on a bipartisan basis, the U.S. Congress passed the Global Catastrophic Risk Management Act of 2022 requiring the Department of Homeland Security to coordinate an expert assessment of global catastrophic and existential risks. The Department of Homeland Security published the first Global Catastrophic Risk Assessment two weeks ago, and reached some important — and one surprising — conclusions.1

The legislation provided key definitions:

The term ‘‘existential risk’’ means the potential for an outcome that would result in human extinction.

The term ‘‘global catastrophic risk’’ means the risk of events or incidents consequential enough to significantly harm or set back human civilization

at the global scale.

The term ‘‘global catastrophic and existential threats’’ means threats that with varying likelihood may produce consequences severe enough to result in systemic failure or destruction of critical infrastructure or significant harm to human civilization.

Congress requested that the assessment focus on six areas of risk:2

the use and development of artificial intelligence (AI);

asteroid and comet impacts;

sudden and severe changes to Earth’s climate;

nuclear war;

severe pandemics, whether resulting from naturally occurring events or from synthetic biology;

supervolcanoes;

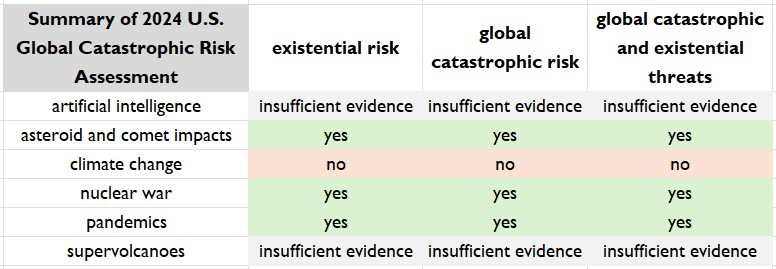

Using the key definitions across these six categories, the table below summarizes my reading of the report.

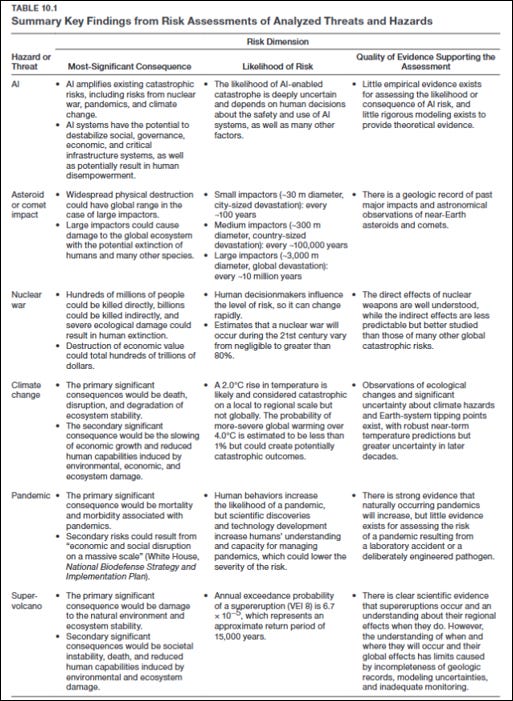

Below is the full summary table from the report, within which, each chapter goes into extensive detail on each of the six risk categories.

The report is well done, and each of the six risk areas are worth their own focused post here at THB.3 In the remainder of this post, I highlight what the report says about climate change — which the report does not identify as an existential risk.

The assessment recognizes that changes in climate have many significant consequences for people and ecosystems, but the corresponding risks are local and regional, not global:

“An important dynamic of climate change effects is that any one mechanism by which climate change creates risk, such as those listed above, although potentially devastating on a local to regional scale, might not rise to the level of a global catastrophe or an existential risk.”4

The report acknowledges diplomatically that activists often characterize climate change as an existential risk, which reflects “subjective values and worldviews” rather than scientific judgments of real-world risks:5

“A strong, international activist movement now exists that engages in advocacy for addressing climate change. That movement emphasizes the urgency of climate change; sponsors civic engagement efforts, including protest and civil disobedience, particularly among youths around the globe; and argues that climate change is a potential existential risk. . . although social movements reflect a genuine and legitimate concern about climate change’s potential risks to society, they are not necessarily grounded in objective assessment of those risks.”

The report acknowledges some of the extreme claims found in the scientific literature from those in the catastrophist planetary boundaries community as well as some of the outlier work in climate econometrics. However, the assessment largely rejects these outliers and is very clear in its conclusion that climate change does not present a catastrophic health risk — even over the course of a century:

“Although there is no accepted determination of what would constitute a global catastrophic health risk from climate change, authors of at least one report defined it as a mass-mortality event taking the equivalent of 25 percent of the population. For the United States, based on the 2020 population (330 million), percent would mean approximately 80 million people, or 2 billion for the estimated global population in 2022 of 8 billion. . . Mortality of this magnitude would effectively be ten times that of the 1918 influenza pandemic. These values suggest a very high bar for catastrophic risk. . . No published study has suggested the possibility of a singular mass-mortality event of this magnitude, nor is there evidence of an indirect mechanism, such as collapse of global food supplies or climate-mediated pathogenesis, that would result in such high rates of mortality. Even with cumulative losses over a century, mortality would not meet these thresholds.”

The bottom line: Climate change is important and poses significant risks that will require continued policy development and implementation in mitigation and adaptation — but climate change is not an existential risk. The world does indeed face existential risks and we should take care that concern over climate does not overshadow these other risks.

Last night I had the chance to give a talk to a wonderful group of thoughtful and informed normal folks in downtown Denver. After the event a women came up to me and asked if I was afraid of climate change. I responded that I was not, for the simple reason that despite the very real risks of changes in climate, we are focused on those risks. I told her that I worry much more about the things that we are not paying attention to, noting that the COVID-19 pandemic arose following a long period where there was little attention or concern about pandemics among most scientists or policy makers.

In a paper I wrote almost a decade ago, I warned that the catastrophes of the 21st century may — like COVID-19 — come from places not at the center of our attention:

I suggest three types of catastrophes lie ahead. The familiar – hazards that we have come to expect based on experience and knowledge, such as earthquakes and typhoons. The emergent – hazards that are the product of a complex, interconnected world, such as financial meltdowns, supply chain disruption and epidemics. The extraordinary -- hazards that may or may not be foreseen or foreseeable, but for which we are wholly unprepared, such as an asteroid impact, massive solar storm, or even fantastic scenarios found only in fiction, such as the consequences of contact with alien life. I will argue that our collective attention and expertise is, perhaps understandably, disproportionately focused on the familiar. The consequence, however, is a sort of intellectual myopia. We know more than we think about the familiar and less than we should about the emergent and the extraordinary. Yet our ability to deal with the hazards of the future likely depends much more on our ability to prepare for the emergent and the extraordinary.

The first Global Catastrophic Risk assessment by the U.S. government is an excellent starting point for a continuing discussion about catastrophic risks and how we might better prepare for them. It tells us that where our focus lies may not be where we find the greatest risks.

Thanks for reading! I welcome your comments and critique. THB is a community and the work done here is shaped every day by my interactions with this community. If you are new to THB — Welcome! — please be sure to check out the THB About page. THB is supported by its community — That means I work for you and thanks to you. Please consider joining this community as a paid THB supporter.

Specifically: “The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate and FEMA requested the Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center’s (HSOAC’s) support to conduct such an assessment . . . [which was] conducted in the Disaster Management and Resilience Program of the RAND Homeland Security Research Division, which operates HSOAC. . . The Homeland Security Act of 2002 authorizes the Secretary of Homeland Security, acting through the Under Secretary for Science and Technology, to establish one or more federally funded research and development centers (FFRDCs) to provide independent analysis of homeland security issues. RAND operates HSOAC as an FFRDC for DHS under contract 70RSAT22D00000001. The HSOAC FFRDC provides the government with independent and objective analyses and advice in core areas important to the department in support of policy development, decisionmaking, alternative approaches, and new ideas on issues of significance.”

The legislation requires that the assessment be updated no less than every 10 years. I would recommend a much more frequent updating, annually or biennially. There are a number of topics I’d suggest adding to the list as well — See my paper on Catastrophes of the 21st Century.

The quality and orientation of the GCRA stands in stark contrast to the U.S. National Climate Assessment (NCA). The NCA was organized out of the White House, with heavy influence from political appointees and activist groups. The GCRA was conducted in an independent FFRDC (Rand Corporation) overseen by a federal agency and far from the reach of political appointees. There is a lesson here.

GCRA: “The IPCC’s special report, Global Warming of 1.5°C, for example, does not identify climate change as an existential risk to humanity.”

The report does not acknowledge that the U.S. president and many other federal agencies (like NOAA) have characterized climate change as an existential threat. That is probably smart politics by the report’s authors, but it also suggests a very large future challenge of realigning U.S. government perspectives and policies with the state of scientific understandings.

Thanks for highlighting this, Roger. I was disappointed that Congress did not include the other item in your final quote, a massive solar storm. Trying to run modern economies, especially food supply, when the electrical grid was down for years could see a lot of deaths.

Great piece, Dr. Pielke. Does this mean RCP 8.5 can finally be stricken from future consideration? Better yet, does this mean Congress can look at climate legislation with a less urgent and more long range perspective? Stop looking for quick fixes (renewables) and figure out how to reduce costs of better, sounder, and more reliable energy?