The Incredible Absence of U.S. Science Advice and the Covid-19 Pandemic

A look at why the United States government was totally unprepared to deliver expert advice in the pandemic

In the 12 months following April 2009, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control estimated that as a result of the H1N1 pandemic in the United States, there were more than 60 million cases, 274,000 hospitalizations and more than 12,000 people died. The World Health Organization and the U.S. government both declared public health emergencies. Pandemic risk was front and center.

In the decades prior to the H1N1 influenza pandemic, in United States at least, pandemic risk had not been much of a concern, with little attention paid to the topic in Congress or in the Executive Branch. This changed in 2005 when over the summer President George W. Bush read an advance copy of The Great Influenza by John M. Barry, about the 1918 global influenza pandemic.

The book captured Bush’s attention, and in November, 2005 in a speech (also below via YouTube) delivered at the National Institutes for Health Bush announced a major new program, the National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Response. Bush warned, “Because a pandemic could strike at any time, we can't waste time in preparing.”

There can be no doubt that Bush’s leadership on pandemic preparedness was prescient and addressed a major oversight in U.S. public health and emergency planning. But the actions taken to put into place preparations for a future pandemic had a major oversight — science advice. The lack of attention to mechanisms of science advice in a pandemic would continue through the Obama and Trump administrations, meaning that when the Covid-19 pandemic emerged in early 2020, the United States was hopelessly unprepared to provide science advice to decision makers. The Trump Administration proved incapable of addressing this failure.

Here, in this post, I’ll share some of the data relevant to the U.S. experience leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic collected as part of the EScAPE (Evaluation of Science Advice in a Pandemic Emergency) project that I am leading, which involves assessments of science advice in COVID-19 across 16 countries.

First, let me be clear what I mean when I use the phrase “science advice.” I have found it useful to define three broad categories of “science advice.”

One is what is typically meant when most people use the phrase, and that is expert advice to inform policy or decision making. Expert advice is the subject of my book, The Honest Broker, in which I further characterize four idealized modes of advice: pure science, science arbitration, issue advocacy and honest brokering of policy alternatives. Typically such advice comes from advisory committees, such as those empaneled by the National Academy of Sciences or under the Federal Advisory Committee Act. (Expert advice is also provided as shadow science advice.)

A second category is the provision of data. In a pandemic, relevant data include the number of COVID-19 cases, testing results, hospitalizations, deaths, the deployment of vaccines and so on. By now we are all familiar with COVID-19 “dashboards” that have been developed by governments, independent analysts and international organizations. Reliable data is also essential to informed decision making. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. government also saw notable failures in data collection and provision.

A third category is regulatory guidance, which might be thought of as a crucially important subset of the first case. Regulatory decisions — such as the approval of a vaccine — are typically guided by well-develop processes in the form of formal expert committees. In the United States such committees include the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee of the Food and Drug Administration. The long-standing committees performed well during the pandemic, highlighting the importance of preparation before disaster strikes.

In this post I focus on the first category above, though I will have much more to say about the other two categories in future posts.

Let’s proceed with the bottom-line conclusion:

When the COVID-19 pandemic emerged in early 2020, the United States found itself lacking any high-level government science advisory mechanism or committee to provide expert advice to inform response. This gaping hole in U.S. pandemic preparedness is a subset of broader failures in the overall U.S. pandemic response which collectively were a result of the shambolic leadership of the Trump Administration.

To be clear, this was a failure of political leadership, and not of expertise or competency of those in the U.S. federal government. The U.S. government boasts what is perhaps the world’s greatest concentration of public health knowledge and skills to be found anywhere in the world. Indeed, in 2019, the United States was ranked in the Global Health Security Index as the nation most prepared for a possible pandemic. This makes the U.S. failures all the more incredible.

However, failures in preparedness for the provision of expert advice are not solely the fault of the Trump Administration (but to be sure, the Trump Administration made them worse), and can be traced back in time through the Obama and GHW Bush administrations.

In addition, the U.S. shortfalls in expert advice stand out in stark contrast to the science advisory preparations of other nations, such as the United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea, Netherlands, Italy and others. A comprehensive recounting of U.S. failures goes beyond this short post (but is taken on under EScAPE), but let me cite two important examples.

The Trump Coronavirus Task Force. Most readers will be familiar with this committee, which played out in spring and summer 2020 like a reality TV show, with characters that included Birx, Fauci, Azar, Pence and often, Trump in the spotlight. This was a committee comprised entirely of Trump’s political appointees (with one exception: Dr. Anthony Fauci). This committee was established ad hoc, on the fly, and in any case was tasked with leading pandemic response rather than providing expert advice. Inside details of this committee’s work have started to be shared, and it is not a pretty picture that emerges.

Soon after the pandemic was apparent in early 2020, the Trump Office of Science and Technology Policy and Department of Health and Human Services asked the U.S. National Academy of Sciences to create a Standing Committee on Emerging Infectious Diseases and 21st Century Health Threats—“to serve as a focal point for discussions on how to integrate science into national preparedness and response decision-making, to explore lessons learned and best practices from previous preparedness and response efforts, and to consider strategies for addressing misinformation.” This was perhaps the best opportunity for a course correction necessary to provide effective science advice to inform the Trump Administration pandemic response. However, the committee fizzled out, for reasons that may only become apparent with the passage of time, . The committee apparently still exists, but after an initial flurry of activity, ultimately did very little through 2020.

Let’s now take a look at the longer-term basis for the U.S. failure in high-level expert advice in the pandemic.

The figure below shows the number of mentions of the word “pandemic” by U.S. presidents from Ronald Reagan through Donald Trump (on 31 December 2019, on the eve of the pandemic).

We can clearly see the influence of George W. Bush’s 2005 summer reading, as “pandemic” was barely mentioned by the three presidents of the preceding 20 years. But Bush’s interest did not sustain across presidential transitions, with a notable decline in attention from Obama (who experienced the H1N1 pandemic) to Trump, who barely mentioned the topic through 2019.

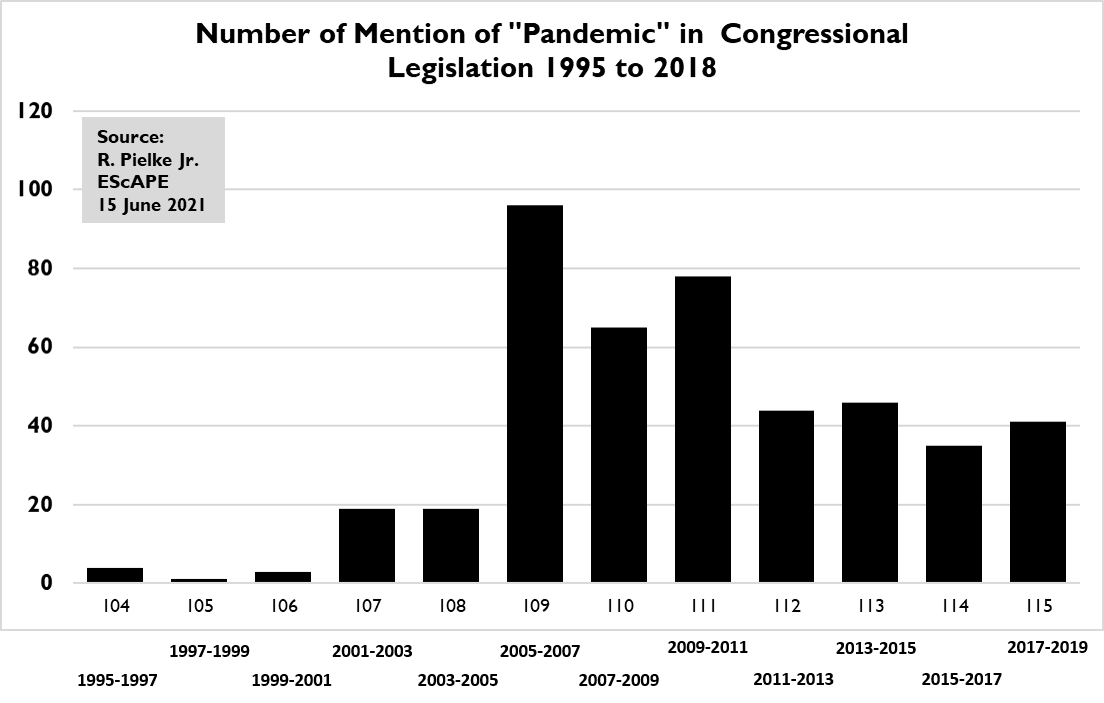

We can see the effect of presidential attention on congressional action in the following graph.

After Bush highlighted the importance of pandemic planning in 2005 and proposed a new national strategy, Congressional attention in the form of legislation (shown) and hearings and reports (not shown) increased significantly in the 109th Congress. Congressional attention also increased in the immediate aftermath of the H1N1 pandemic during the 111th Congress. But then attention waned, as legislators moved on to other things deemed more pressing or important.

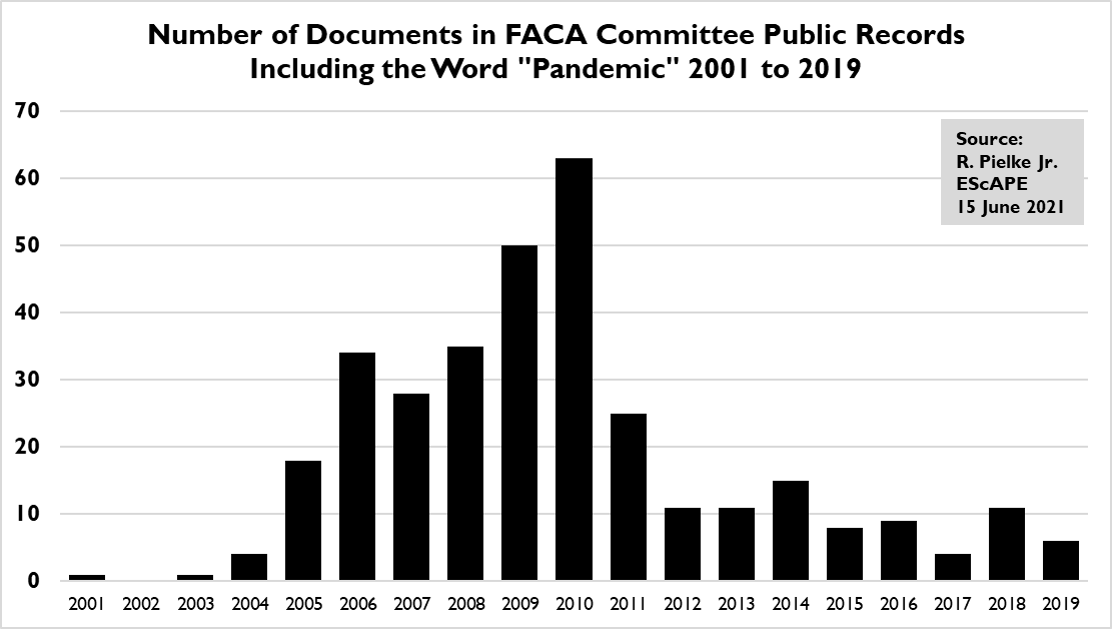

We can see a similar pattern in the focus of attention among science advisory committees of the U.S. government (i.e., FACA committees) as shown in the graph below. The president’s focus on pandemic starting in 2005 led to an increase in attention among expert advisors, as would be expected since the president leads the executive branch.

But that attention was short-lived, and dropped off a cliff after the H1N1 pandemic. From 2012 to 2019, the issue of pandemic was barely mentioned across the 1,000+ FACA committees of the U.S. government.

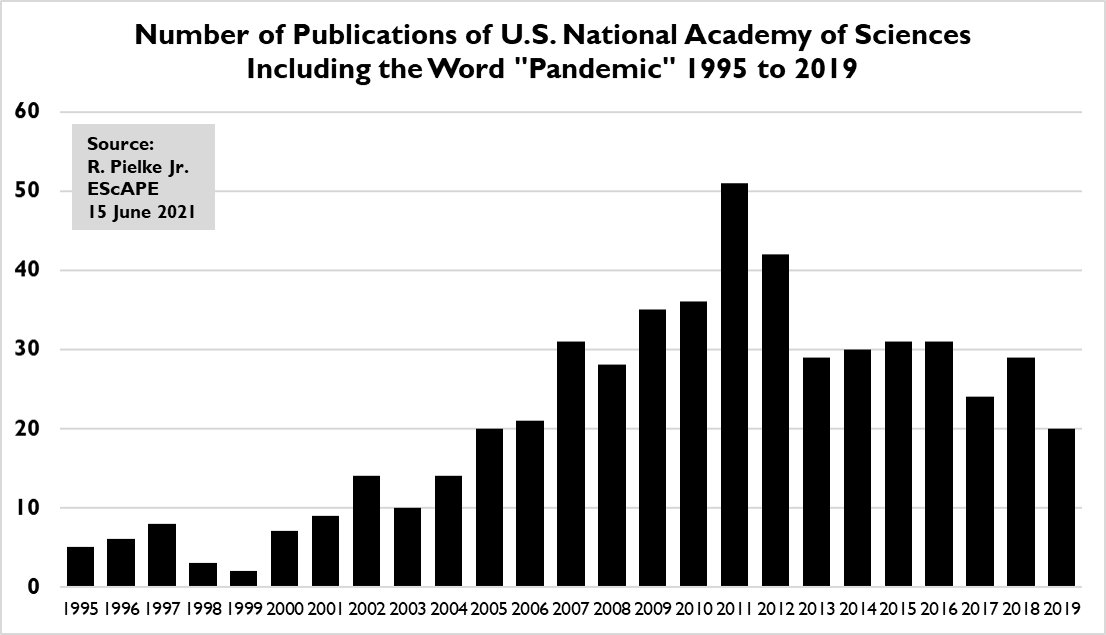

Finally, we can also look at the work of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, which operates by empaneling expert committees at the request of (and funding provided by) the federal government, as well as exhibiting leadership by creating committees it views as needed, using its endowment funds. The graph below indicates that the NAS followed the focus of attention of the president and Congress, with an increase in attention following Bush’s pandemic focus and then dropping significantly after the H1N1 pandemic.

These data tell a story of short-term focus on pandemic by U.S. policy makers and their expert advisors, motived by a moment of presidential leadership and the H1N1 pandemic. However, the focus did not last. At no time during the periods of increased focus were mechanisms of expert advice institutionalized in preparation for a future pandemic. Thus, in January, 2020 the U.S. government found itself without a much needed science advisory capacity as COVID-19 exploded around the world.

This oversight should not have happened. For instance, in 2015, I wrote a paper about the “Catastrophes of the 21st Century” in which I warned that we were increasingly prepared for recently familiar events like hurricanes and earthquakes, but not the recently unfamiliar, like a pandemic or approaching asteroid.

[O]ur collective attention and expertise is, perhaps understandably, disproportionately focused on the familiar. The consequence, however, is a sort of intellectual myopia. We know more than we think about the familiar and less than we should about the emergent and the extraordinary. Yet our ability to deal with the hazards of the future likely depends much more on our ability to prepare for the emergent and the extraordinary.

I argued that we experts in the scientific community have an obligation not to simply follow the focus of politicians at any given time, but to exercise leadership in focusing our attention on risks that exist but may be underappreciated or ignored.

Tomorrow’s threats are unknown and perhaps unknowable. However, this need not stand in the way of a more expansive expert discussion about our collective ability to deal with possible futures. Some scenarios of undesirable futures are certainly imaginable, such as a global pandemic, an asteroid impact or nuclear war (whether inter-state or via terrorism). Expanding our discussions about how we might deal with such unlikely but possible catastrophes may ultimately help us to develop options for dealing with those threats. . .

In the United States, responsibility for the lack of preparation to provide expert advice in the COVID-19 pandemic lies first and foremost with political leaders — especially the administrations of Bush, Obama and Trump. The failure to establish mechanisms of science advice in anticipation of a pandemic is remarkable, given that the U.S. is a science advisory colossus, with an enormous number of expert committees in and out of government. But not for a pandemic.

When the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, the Trump Administration’s leadership incompetence across the board also was demonstrated in its inability to organize high level expert advice, resulting in confusing, incorrect and pathologically politicized information being provided to the public and public health decision makers. The Trump Administration’s failures were many, and science advisory shortfalls are just one part of that picture.

It is not clear that the Biden Administration has yet addressed the failures of pandemic science advice documented here. They should, because as we’ve seen, expert advice is really important.

The reference to use of the word "pandemic" in legislation and in presidential addresses raises a query: Does this take into account that legislation usually stays in effect for a number of years (and possibly indefinitely until repealed), and therefore is cumulative to some extent and once a push for legislation has occurred and been successful (wholly or partially) then it would seem there would be less legislation in subsequent years because less was needed (since some had already been passed) thus resulting in less use of the word by subsequent Congresses. There would be less need for a President to speak about it (I am assuming a great deal of Presidential speaking concerns pushing for legislation), since some of the legislative work had already been accomplished. I am not saying this happened actually happened. I am merely pointing out that the lessening of the use of the word "pandemic" between George W. Bush and Barack Obama might not indicate a lessening of attention by the Obama Administration but an indication of success by the Bush administration. I guess this is a correlation vs. causation problem of some sort.

"Data" surely includes knowledge of where people (individuals) happen to be at particular times, informed by existing knowledge of transmission pathways, & what is their state of immunity (history of prior infections & vaccinations). Armed with that perfect knowledge, policy actions are constrained by ability to confine further contacts between people.

Then, *without* that knowledge of precise who/what/when/where & *without* ability to severely contain groups (or entire cities), control of some agents is not possible.