In 2024, the world experienced $298 billion dollars in catastrophe losses related to weather events, according to Munich Re, which just released its annual tabulation.1 Munich Re attributes the losses to — what else — climate change, dramatically announcing that “climate change is showing its claws” and “climate change is taking its gloves off.”

The Munich Re attribution claim contrasts starkly with how its largest competitor, Swiss Re, characterizes 2024 loss totals, identifying economic development as the “main driver” of increasing loss totals:

"Economic development continues to be the main driver of the rise in insured losses resulting from floods, but also other perils, seen over many decades. However, with natural catastrophe risks rising and higher price levels, the annual increase of 5–7% in insured losses will continue, and protection gaps could remain high. This highlights the need for adaptation in combination with an adequate insurance coverage that can support financial resilience."

To better understand global disaster losses, it is helpful to place them into the context of the global economy, which like the climate, also changes over time. The methodology and data are described in detail in this 2019 paper:

Pielke, Jr. R. (2019). Tracking progress on the economic costs of disasters under the indicators of the sustainable development goals. Environmental Hazards, 18(1), 1-6.

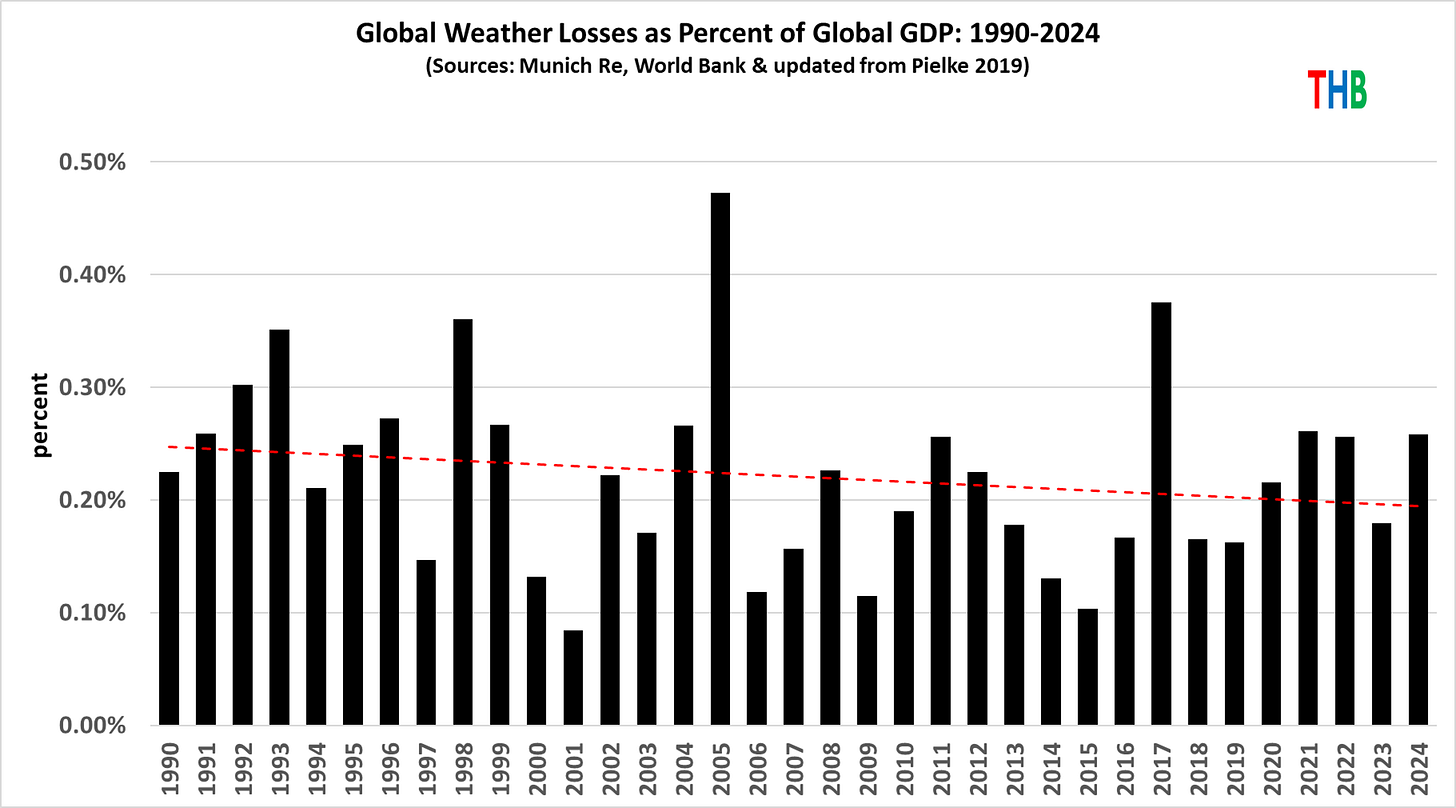

The figure below updates the time series of Munich Re’s disaster loss record as a proportion of global GDP.

Loss in 2024 were about 0.26% of global GDP, similar to 2021 and 2022, much lower than 2005 and 2017, and higher than 2018, 2019, and 2023. Since 1990, the overall trend is down — from about 0.25% of GDP in 1990 to about 0.20% in 2024. In the 1990s catastrophe losses as a proportion of GDP exceeding those of 2024 were common.

The data in this graph is good news — in terms of economic losses, extreme weather has less of an impact today than it did 35 years ago.

Last fall, Verisk published an estimate of expected global insured losses (specifically, AAL or average annual loss) of $151 billion. If we double that, as is common practice to estimate overall (insured and uninsured) losses, we get $302 billion, which is almost exactly the actual loss total for 2024. Losses in 2024, at about $300 billion, were large — but not at all unexpected or unusual.

Verisk’s 2023 average annual loss estimate was $133 billion — meaning that expected insured losses jumped by $18 billion in just one year, from 2023 to 2024.

Bill Churney, President of Verisk’s extreme event solutions, attributes this alarming surge in catastrophe losses to several key factors.

The primary drivers include the growth in exposure values, fueled by ongoing construction in high-hazard areas, and rising replacement costs due to inflation.

While climate change is often cited as a factor, Churney emphasizes that year-over-year increases in exposure and replacement values exert a more immediate impact.

Verisk expects continued exposure growth of 7.2% per year, which means insured losses will continue to mount. Verisk explains:

“While actual annual insured losses over the past five years have been high, averaging $106 billion, they should not be seen as outliers. Our models show the insurance industry should be prepared to experience total annual insured losses from natural catastrophes of $151 billion on average, and well more than that in large loss years.”

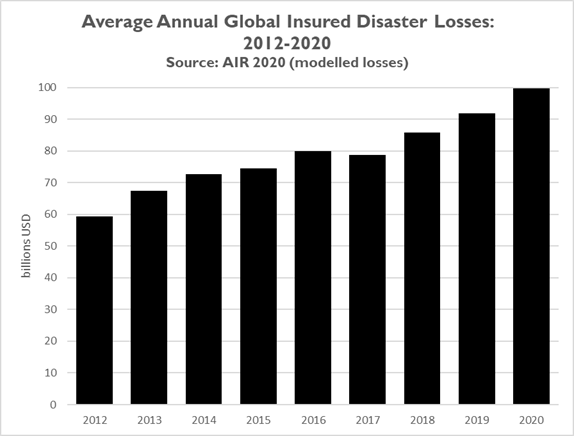

That exposure growth is driving increasing disaster losses is not at all surprising. The figure below shows that over the past decade expected insured catastrophe losses have more than doubled (from ~$70B in 2014 to ~$151 in 2024).

While some promote climate change as the main factor behind increasing losses, Swiss Re acknowledges that it has not yet seen a signal of climate change in losses, even as climate change presents future risks:

“To date, growth in natural catastrophe-related property losses has been mostly driven by rising exposures due to economic growth, accumulation of asset values, urbanisation and rising populations, often in regions susceptible to severe weather events (eg, coastal regions, river fronts and wildland-urban interfaces). In the future, hazard intensification due to climate change is set to add to weather-related losses.”

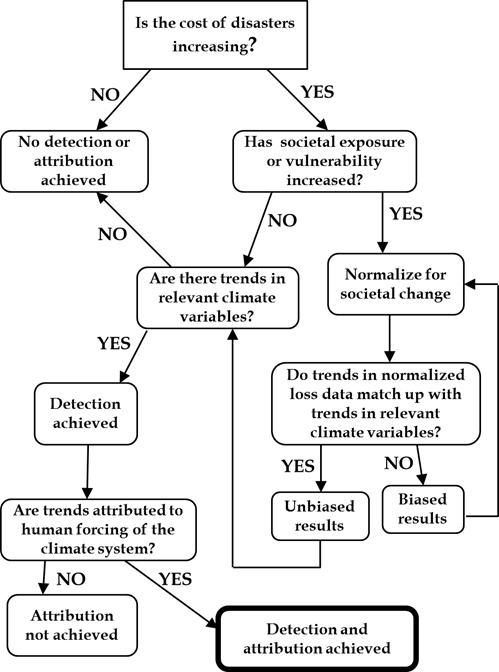

It is of course perfectly reasonable to ask if changes in climate as reflected in the statistics of extreme weather events play some role in increasing catastrophe losses (read more here). Below is a flow chart which shows the logic underlying much of my research over the past three decades exploring the relationships of extreme weather, societal change, and catastrophe losses.2

For its part, in 2024 Munich Re expects profits of more than €5 billion. For 2025, Munich Re expects even greater profits of €6 billion. After climate change has taken off its gloves, it turns out that its claws are not really that sharp.

The easiest thing you can do to support THB is to click that “♡ Like”. More likes mean the higher this post rises in Substack feeds and then THB gets in front of more readers!

If you are a new visitor, Welcome! Read all about THB here. THB is reader supported, which means I work for you — Literally. I like it that way. You can find a readily accessible list of THB series here. THB also has a portal with paid-subscriber only content. So click that subscribe button!

Well over half — 64% or $190B — of these losses occurred in the U.S., and most of these losses resulted from hurricanes ($105B). Thus, “global catastrophe losses” is really a misnomer, as global losses are overwhelmingly U.S. hurricane losses (see Mohleji and Pielke 2014 where we first documented this fact).

Of course, those looking for trends in extreme weather should look at weather and climate data, not economic loss data.

I wish you could get that chart of Global Weather Losses as a percent of Global Gdp 1990-2024 on the front page of the New York Times.

You might want to share this post with The Editors of The Free Press who infer - in their January 9th piece 'Paradise Lost' - that climate change is a significant proximate contributer to the Los Angeles wildfire disaster.