One of the wonderful things about science is that research results cannot be consistently anticipated. That’s why we do the research.

That research doesn’t always come out how we expect is particularly problematic for partisans who expect research to provide results in alignment with their political commitments.

So you think hurricane landfalls have become more frequent in the U.S.? Think again. Or you think that childhood vaccination is more risky that no vaccination? Think again.

Evidence matters.

As longtime THB readers will know, for well over a decade I have studied the use of science in gender eligibility regulations in elite sport, and in track and field (or athletics) in particular.

For instance, in 2018, I — along with Ross Tucker and Erik Boye — discovered that research used to support regulation of female athletes had relied on compromised data, rife with errors that, when corrected, undercut the asserted scientific justification for regulations. That led to a major admission of error from World Athletics, which today no longer cites the fatally flawed study. Our work won the intellectual argument, but did not much matter for the regulations. That is how politics works sometimes.

Based on that work, in 2019, I was a pro-bono expert witness before the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) in Lausanne, Switzerland in the arbitration of South African middle distance runner Caster Semenya against World Athletics (then called the IAAF), which she lost in a split decision.

The issue involves a small group of women that World Athletics claims have an unfair performance advantage over other women, due to their unique biology. These women are referred to variously as intersex athletes, athletes with Differences in Sexual Development (DSDs), or athletes with natural variations in their biological development (natural variations).

All of these women were registered female at birth, maintained that identity into adulthood, and then throughout their athletic careers. This issue is not about transgender athletes who have at some point in their lives legally changed their gender. That too is an important issue, but very different from the one I am discussing today.

In 2023 World Athletics implemented a new set of regulations governing women with natural variations in their sex development (its fourth or fifth iteration of such regulations since 2011) called the Eligibility Regulations for the Female Classification (Athletes with Differences of Sex Development).

Earlier this month, World Athletics announced yet another iteration of the regulations, which they previewed as being even more restrictive:

It is our role, as the global governing body for athletics, to ensure that our guidelines keep up with the latest information available to maintain a fair and level-playing field in the Female Category.

The current and proposed regulations prohibit women with certain biological characteristics (detailed in the regulations) from participating in the women’s category of competition. To achieve eligibility to compete with other women, the 2023 regulations require these women to undergo medical treatments that lower their testosterone levels. The forthcoming revision to the World Athletics regulations appear to implement a full ban on their participation.

To their considerable credit, World Athletics has been very clear that,

“[I]n no way are [the regulations] intended as any kind of judgement on or questioning of the sex or the gender identity of any athlete.”

That means that the issue here is not about identity, who is a man and who is a woman — World Athletics fully accepts that these women are women. Rather, the issue is about the presence of an unfair performance advantage that “athletes with DSDs” are alleged to have over other women in competition, thus necessitating regulatory intervention.

Here are some examples of World Athletics’ claims about this subset of women having an unfair performance advantage:

Women who fall under World Athletics’ (and previously IAAF’s) regulations have “a performance advantage of at least 5-6% over a female athlete with testosterone levels in the normal female range.”

The Semenya vs. IAAF (2019) CAS panel summarized the IAAF’s claims of unfair advantage as follows (emphases added):

"[T]he IAAF's position is that the evidence demonstrates that the performance advantage that [these] athletes enjoy by virtue of their elevated endogenous testosterone is the same as the performance advantage that the hormone confers on all male athletes." (Semenya 562)

“The IAAF contends that, for sporting purposes, individuals with [these natural variations] are biologically indistinguishable from males without a DSD and have been shown to dominate in sport over "biological females" who, the IAAF asserts, have no chance to win when competing against such "biologically male" athletes. This is because, it says, from a biological perspective [these] athletes are the same in every material respect to male athletes without DSD.” (Semenya 503)

One of the consultants testifying at the Semenya case for IAAF argued that female athletes who fall under the regulations (emphases added), “have exactly the same performance advantages over female athletes as non-DSD males athletes have. On average, this advantage is between 10% and 12% in running events, while it may be as high as 20% in jumping events.” (Semenya 353)

These statements beg for evidence to support the claims. Is it actually true that these women are “indistinguishable from males” in terms of their athletics performance, alleged to have “exactly the same performance advantages” that men have over women? Is the asserted performance advantage 5-6% or 10-12% or something else?

If evidence shows that this subset of women do indeed have an unfair performance advantage over other women, then eligibility regulations would appear to make sense. Alternatively, if evidence does not support claims of an unfair performance advantage, then regulation would be unnecessary.

Evidence matters.

This issue is about the possibility of an unfair performance advantage that a small subset of women may have over other women in competition.

Can we tell by just looking if a subset of women might have an unfair performance advantage over other women? No.

How about by examining their biological or physiological characteristics? Nope.

Sport is like science in this way — If we could readily anticipate results we wouldn’t need to have competition.

Logically, it only makes sense that to assess the possibility that a subset of women might have an unfair performance advantage over other women requires looking at evidence of performance, and assessing whether any quantified advantage is unfair.

Evidence matters.

A direct analogy is athletes who run on protheses — so-called “cheetah blades.” CAS has consistently ruled that an athlete cannot be banned simply because they run on the blades — The issue here as well is not about the athlete’s identity or physiology, but unfair advantage. CAS also has ruled that World Athletics bears the burden of proof to support any regulation of eligibility, to show that the use of the blades confers an unfair performance advantage over other competitors.

If World Athletics cannot meet its burden of proof, then the default position is to allow the athlete to compete. Evidence has in the past supported inclusion and exclusion of athletes who run on blades — Oscar Pistorius famously ran in the Olympics and another runner, Blake Leeper (shown above), was not allowed in the Olympics. Both decisions were grounded in contested evidence of advantage (or not) in performance and adjudicated before CAS.

Remarkably, in the nearly 16 years since the regulation of female “athletes with DSDs” has been a central focus of World Athletics, there has not been a single study of the performance of these women in comparison with other women to assess the possibility of an unfair performance advantage. There has been no direct evidence to support the regulations, which have become increasingly restrictive nonetheless.

That is, until now.

I and seven colleagues from the U.K., Canada, and Switzerland have just published as a pre-print — Gollish et al. 2025 — the first such study.1 We compare in-competition performances of nine women who fall under the 2024 World Athletics DSD Regulations (and who have publicly stated so)2 against the performances of hundreds of other women who participated in the Paris 2024 Olympic Games.3

You should read the full paper for all the details, of which there are many. What follows is a short overview of our analysis.

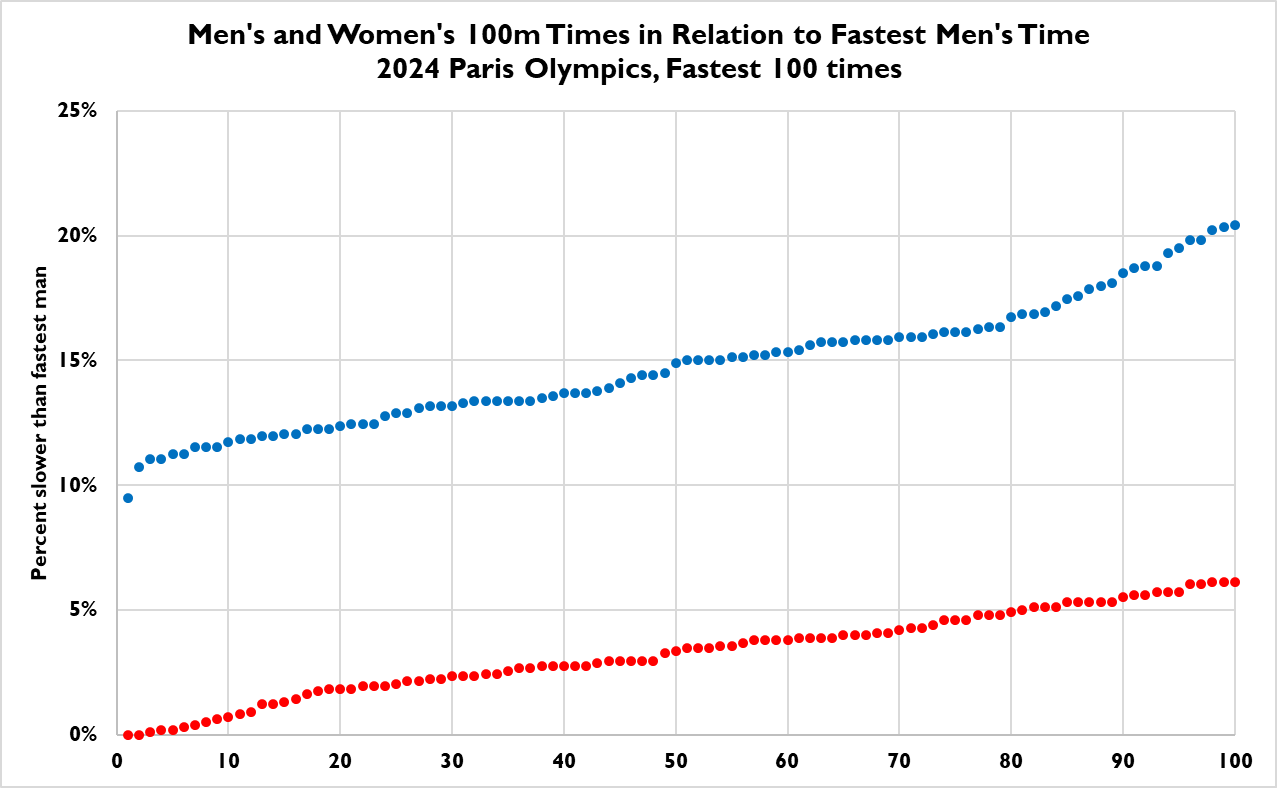

For the 100m, 200m, 400m and 800m events we created a visualization of the top 100 performances at Paris 2024 for both men’s and women’s competition, shown below for the 100M.4 We use the fastest men’s time as the baseline, and show all other results in relation to that baseline. For example, if the fastest man ran 10.0 seconds on the 100M, then 5% on the figure indicates a time of 10.5 seconds, or 5 percent slower. On the graph, red indicates the men’s performances and blue the women’s performances.

Some things to note about the data, which is fully consistent with past research:

Women’s times, at all rankings from 1 to100 are consistently about 11-13% slower than the equivalent men’s performance.

There is no overlap of men’s and women’s performances.

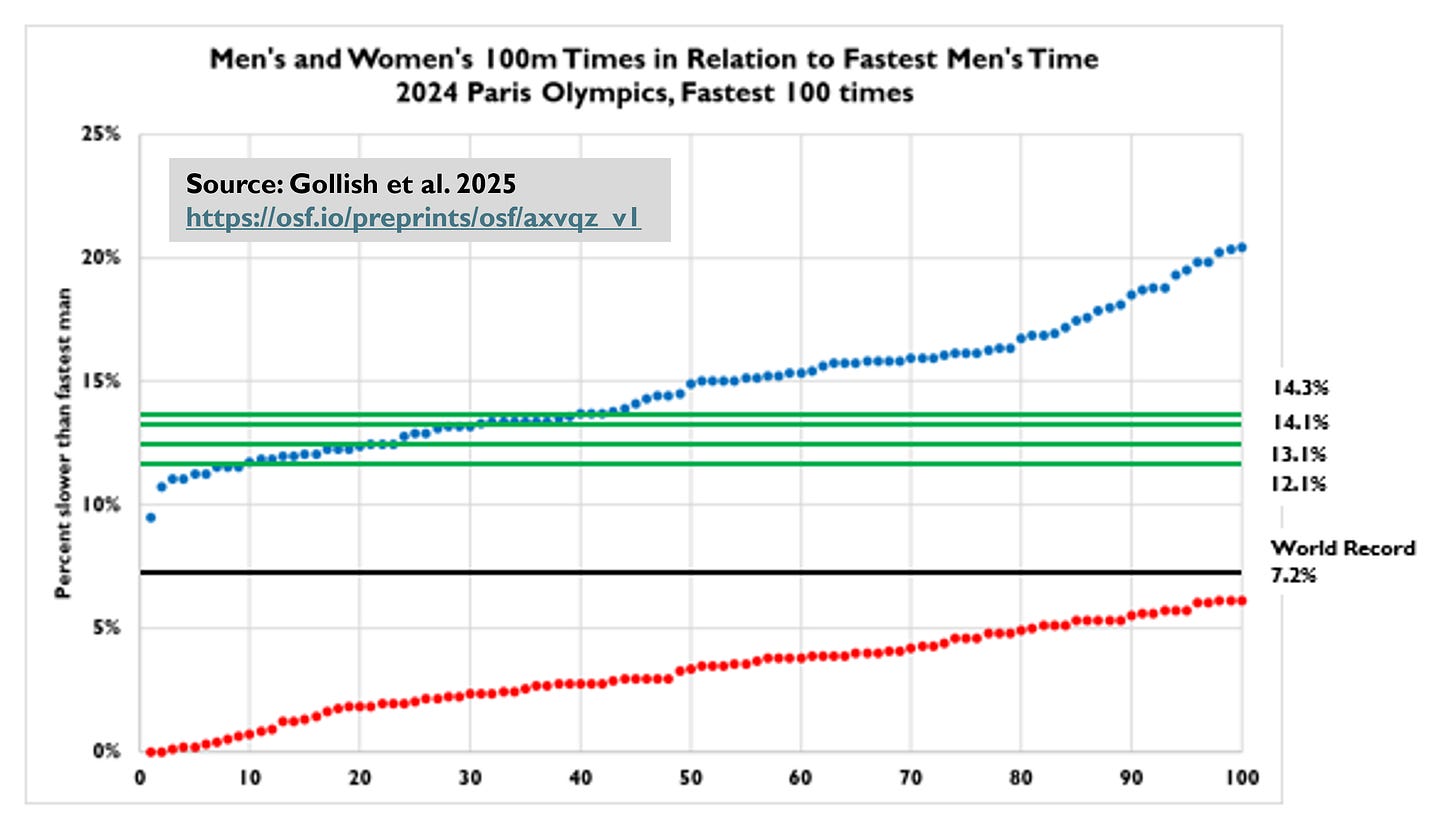

The next thing we did was identify the lifetime best official in-competition times for the 100M for the of the subset of the nine athletes at the focus of our study who fall under the World Athletics DSD Regulations. We use lifetime best times because these performances represent the fastest that these women have ever run at this distance, building in considerable conservatism to our analysis.

The figure below shows with the green lines the lifetime best performances of the four (of the nine) women with official in-performance times at the 100m, as reported by World Athletics. We also display with the black line the women’s world record time at the 100m.

Some things to note about the data5:

The career best times of the four women who are currently banned from competition (unless they undergo medical interventions) are consistent with performances of other women at Paris 2024.

None of these women has approached the women’s world record.

None of these women perform anywhere close to men.

We repeat this analysis for the 200m, 400M, and 800M, with consistent findings.

Here is what we write of the findings in our pre-print:

[T]he career bests of these nine athletes with natural variations fall entirely within the distribution of women’s performances at Paris 2024, for the 100m, 200m, and 400m, and that all but two athletes fall within the distribution for the 800m. This analysis would likely look different if the results compared the personal best of each of the athletes who competed in Paris, rather than on their performance during the games. Of particular note, is the 800m, which is often run tactically at a championship event compared to the 100m, 200m, and 400m run at full effort. Consequently, this analysis is very conservative in that it captures the career best of these 9 women compared to the results of a single Olympic Games. None of the identified women have a women’s world record or threatened a world record. Similarly, none of these nine athletes have performances anywhere close to the distribution of men’s performances at Paris 2024. In the 200m, 400m, and 800m there are an equal number of regulated women in the top and bottom half of each distribution of Paris 2024 performances.

Does evidence in performance of the women currently banned by World Athletics indicate an “insuperable advantage” or “exactly the same” advantage that men have over women?

The answer to this question is perfectly clear:

No, these women do not have an “insuperable advantage” over other women nor do they perform like men.

We conclude in our preprint:

A comparison of career best times of the nine athletes versus the results from a single event at a single Olympics, arguably with moderate times, biases the analysis in favor of accentuating the performances of the nine athletes in relation to other women. Even with this bias, it is undeniable that the performances of the women who fall under the WA DSD regulations is consistent with that of other women, and inconsistent with the performances of men.

Specifically, the analysis in this paper shows that the women who currently fall under the 2023 WA regulations run like other women, with performances that span a wide range of the distribution of women’s performances in Paris 2024. The claims of WA and conclusions of the Semenya CAS panel are thus simply not supported by the available evidence.

In our paper we quote sport scientist Ross Tucker — who testified in support of Caster Semenya in 2019 and has since changed his views6 — who recently invoked a relevant analogy of regulating accomplished swimmer Michael Phelps because he has a unique physiology:

Now, one could have a debate over whether we *SHOULD* think about creating a category for small feet or short arms. If we did this, then [Michael] Phelps' supposed advantages would become 'outside of category', and we'd say that he's not allowed to swim in the protected category, right? But we don't need to do this, because the advantages that he [Phelps] has are tiny compared to what male advantage does to performance. Phelps wins by 0.5%. Males win by 12% (compared to females). By scale, then, these advantages are orders of magnitude different. . . The only way around this is to say that we should create a category because Advantage X is so large it also overwhelms the result. But it doesn't - as mentioned, by scale, what Phelps has over males is tiny compared to what males have over females.

Tucker is correct that the presence and magnitude of a performance advantage matters when we are considering implementing eligibility regulations for gender or arm length or anything else.

The 2015 CAS decision in Chand vs IAAF also made this point clearly (emphasis added):

The Panel considers the lack of evidence regarding the quantitative relationship between enhanced levels of endogenous testosterone and enhanced athletic performance to be an important issue. While a 10% difference in athletic performance certainly justifies having separate male and female categories, a 1% difference may not justify a separation between athletes in the female category, given the many other relevant variables that also legitimately affect athletic performance. The numbers therefore matter.

Evidence matters. In the case of the regulation of women with natural variations in their sex development, available evidence indicates that these women do not have an “insuperable” performance advantage over other women.

The restrictive regulations being pursued by World Athletics for more than 15 years are thus unnecessary.

You can download our preprint at the link below. We welcome comments and suggestions as it makes its way through the peer review process.

Gollish, S., Heffernan, S. M., Herbert, A., Pape, M., Sabiston, C. M., Stebbings, G., … Pielke, R., Jr. (2025, February 21). Running Like a Girl: Athletics Performance of Women Whose Eligibility is Subject to World Athletics DSD Regulations.

Some brief notes on comments to this post. First, this post is not about transgender athletes. There are plenty of posts here at THB on that topic where you are welcome to comment, but not on this post — any such comments will be deleted and the poster placed into the THB penalty box for a short while. Second, I will not allow specific comments about the medical or biological characteristics of any individual. Privacy and dignity matter. Third, the usual high standards of THB discussion are expected on all posts and at all times, which readers have come to expect. We will keep that up. With that, let’s discuss!

The easiest thing you can do to support THB is to click that “♡ Like”. More likes mean that THB gets in front of more readers! Go on!

Our paper is currently under review at a peer-reviewed journal. All data for our analysis is publicly available from World Athletics. We do not name the nine athletes in the paper nor do I in this post, as a matter of respect and in recognition that many of these athletes have been subject to harassment. Anyone wishing to replicate our work can easily identify them through media reports and CAS judgments, as we have.

The WA 2023 regulations provide us a natural experiment. The nine women have all refused to undergo medical treatment, and there is no woman in competition that is undergoing such treatment. Thus, we know that Paris 2024 included only women who were not excluded by the 2024 regulations.

Disclaimer: The pre-print is our joint product. This Substack post shares my views alone.

If there were less than 100 performances, then we used all that were available. There are some performances available for longer distances, but not many, and with results perfectly consistent with those reported in the paper at the four shorter distances.

We do not perform formal statistical tests on the results, as such tests are inappropriate in this context. However, anyone who would like to run such tests is welcome to do so. They will (fairly obviously) arrive at results consistent with those of our paper.

Tucker, who I have collaborated with several times, appears to have been swept up in anti-trans activism, a stance which may underly his change of perspective on this subject. Even so, his analogy quoted here is apt.

I think that is very important research. Unfortunately, it may not completely answer the question of whether women with DSD have on average an athletic advantage over regular women. Here’s a quote from the paper linked below:

“The incidence of 46,XY DSD in the general population is estimated to be 1 in 20,000 births. In comparison, the prevalence of this condition among female athletes participating in the World Championships was 7 in 1000, that is, 140-fold higher”.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7159262/

What is your take on this research?

Your use of "anti-trans" activism in foitnote 6 is unfortunate and biased. One can hold that biological men who have gone through puberty should not compete with biological women and still not be anti-trans. Other than that and without reviewing the data, I agree with your conclusion. Even if there were a significant difference, if these athletes meet the criteria of a female, however we define that (with total understanding of the inherent ambiguity of that determination),they should allowed to compete as women.