Making Sense of Debate Over Transgender Athletes: Part 1

Classification debates are commonplace in policy and often reflect essentialist versus constructivist views of the world

Classification sits at the center of many hotly debated policy issues. Who is prioritized for Covid-19 vaccination? Who should receive $1,400 in federal assistance under the American Rescue Plan Act? In order for policy implementation to occur, choices must be made and lines must be drawn.

Classification decisions are fundamental in sport as well. Who makes the Olympic team? Who is violating anti-doping rules? Who gets to compete as a female?

It is on this last question that we currently find growing debate over transgender athletes — those individuals, according to the Human Rights Campaign, “whose gender identity and/or expression is different from cultural expectations based on the sex they were assigned at birth.”

People of good faith hold different views as to what policies should be in place governing the participation of transgender athletes in sport — especially transgender females. In this sense the issue is no different than debates such over who should be first in line for Covid-19 vaccination. In another sense, the transgender and sports debate is different because it sits closer to matters of human dignity and discrimination. Given history and context, this is territory that must be discussed carefully and respectfully.

This is the first is a series of posts that takes on debate over transgender athletes, which are complicated, nuanced and require some effort to both explain and to understand. In this post I’ll explain a distinction between essentialism and constructivism and why it matters in debates over transgender athletes. This post doesn’t provide answers or a recommended way forward, that is to come later in this series.

Commonly, classification arguments look to science to adjudicate tough choices. Such arguments reflect a Platonic ideal which holds that all things have an immutable essence, which we only need to discover in order to properly categorize. If categorization decisions simply reflect identifying the truth, then that determination can be made objectively and authoritatively, typically through the application of authoritative science and expertise.

Such essentialism sits in contrast to constructivism, which holds that classification decisions reflect choices that we make in creating categories that we then use to make sense of and move within the real world, rather than some immutable reality. A constructivist outlook can make classification decisions much more difficult, because it opens up the possibility that classifications can be made in different ways.

Debate over essentialism versus constructivism can be found not only in policy settings, but in science as well. For instance, does the periodic table of the elements reflect the true nature of the universe that we have revealed or is it a non-unique taxonomy that we created to make sense of the universe? Fortunately, grappling with policy-relevant classification issues does not depend on resolving such questions! In practice, our perspectives (and policies) often reflect a mix of essential and constructivist views, adding to the complexities.

These are abstract concepts so let’s illustrate them with a more grounded example.

In 2013, Adnan Januzaj, a Belgian-born soccer player who then played for Manchester United, was being considered for naturalization as a British citizen, thereby qualifying him for consideration for inclusion on the English national team. In response to this possibility, Jack Wilshire — a member of the English soccer squad — opposed Januzaj’s eligibility, arguing, “an English player should play for England.”

In response, Keven Pietersen, who was born in South Africa but represented England in cricket, observed that Wilshire’s stance “would leave him [out] and a number of other leading sports stars, including Olympic hero Mo Farah, who was born in Somalia, and the Kenyan-born Briton Chris Froome,” who had then just won the Tour de France. What makes someone “English”? Pietersen asked.

Wilshire was reflecting an essentialist perspective — that nationality reflected something immutable and fundamental to an individual, whereas Pietersen was reflecting a constructivist perspective — that nationality is a function of what we say it is, and as such, it can be changed. The debate was rendered moot when Januzaj chose to play for Belgium, but it very well illustrates a difference in perspectives commonly found in classification debates.

Such different perspectives also help to explain why people so often talk past one another when arguing about classification policies. They might disagree not just about the policy alternatives, but more fundamentally about the nature of the world we live in.

You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to see how debates over the essence of nationality can overlap with some pretty horrific views associated with racism, discrimination, supremacy, ethno-nationalism and even eugenics. It is also not hard to see how essentialist-versus-constructivist perspectives map onto the debate over transgender athletes.

If the categories of male and female are immutable scientific truths, then categorization for purposes of policy requires simply identifying which category a person fits into by the relevant objective criteria. Once those criteria are identified, then the individual actually has no say in such categorization, as their categorization is immutable and fundamental to their essence. A good example of such a category (so far, at least) is a person’s biological age dated to their birth. If sex is just like age, then categorization is easy-peasy.

Alternatively, if categories of male and female are instead just simple binary categories invented by us to make sense of the world, then it opens the possibility that the categories are not unique (e.g., there may be more than two). Further, if these categories are created by us, then it opens the possibility that people can change categories, just as they do with nationality. Such a perspective makes the world more complicated than essentialism, because it forces us to consider how we create categories as we are also applying them, and as such the possibility that they might be malleable.

Some try to bypass the essentialist versus constructivist debate by arguing that gender is constructed whereas biological sex is essential. From this perspective, the choice then in policy is not about classification, but about whether our decisions are to be about gender or sex. However, such a stance actually makes the classification problems more difficult not easier, as instead of two categories for classification, it instead creates four (imagine a 2x2 matrix with sex and gender on the axes). The idea that four categories will be easier to govern (in any setting) than are two categories is flawed.

Fortunately, laws in many places around the world (not all, to be sure) are moving in a direction that provides some guidance on how we should think about the essentialist versus constructivist debate. Where ever one falls on the spectrum of essentialism-constructivism, there is undeniably a trend in the direction of recognizing — that from the perspective of policy and law — transgender women are women and transgender men are men. In a practical sense, law and policy are increasingly grounded in a constructivist perspective that represents a growing consensus.

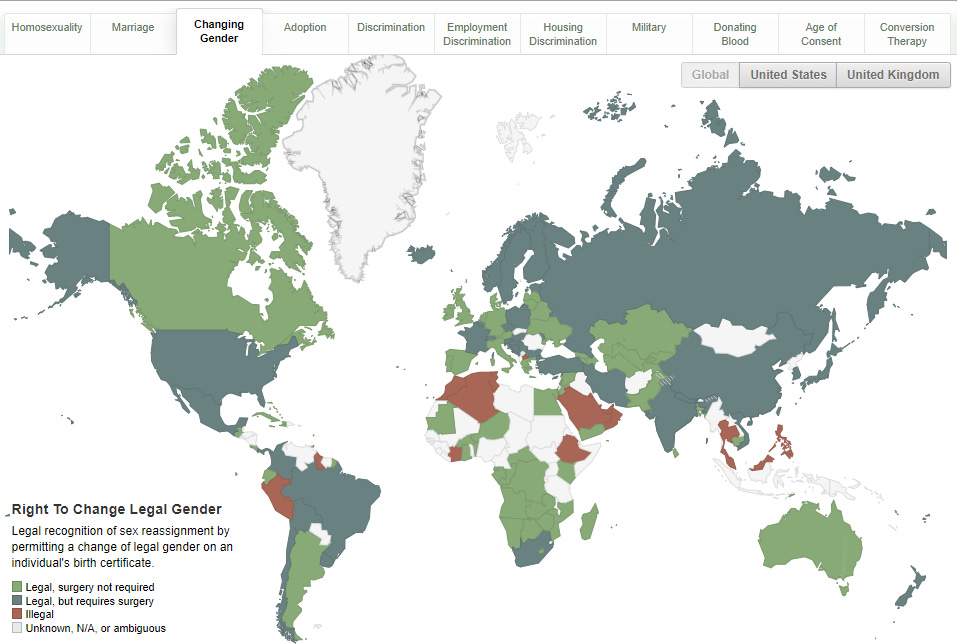

The data bear this out. According to Equaldex, an organization that tracks LGBTQ rights around the world, the right to change one’s gender exists currently in 90 countries, is illegal in 14 countries with 44 “somewhere in between,” as shown in the figure above. Make no mistake, however, issues related to transgender rights remain hotly contested, and will likely be a “growing political flashpoint” of conflict in the United States.

The trend toward legal recognition has, in many places, led to an expansion of legal rights and anti-discrimination rulings. However, this trend has not always been accompanied by inclusiveness in sport. In the United States, so far in 2021 26 state legislatures are considering laws “to exclude trans youth from teams that align with their gender identity.” A proposed law in Georgia would require that youths provide details to officials of their “reproductive organs, genetic makeup, and other medically relevant factors." An irony of these proposals is that the prevalence of transgender athletes in these states is small or non-existent, suggesting that this issue is being used cynically to inflame polarization rather than develop worthwhile policy.

We should all be able to agree that requiring inspection or certification of a child’s genitals as a prerequisite to playing youth sport is invasive and inappropriate. But it is also demeaning and contrary to human dignity for state governments to assert a right to determine an individual’s sex or gender contrary to how that individual views themselves. Such state policies cause real harm to real people.

In sport, classification decisions do need to be made to determine who competes in male and female categories. Anything goes, or open competition is just not an option. At the same time, basing sport classifications on essentialist perspectives about who is male or female comes into direct conflict with the fact that much of the world has adopted a constructivist approach to legal rights and anti-discrimination.

The consequence of these conflicting approaches is to treat transgender athletes as different, lesser and ultimately the object of what inevitably must be characterized as necessarily subject to justifiable discrimination.

This is not right.

Fortunately, there are ways forward that might be found acceptable to both essentialists and to constructivists, and the apparent contradictory implications of different laws and policy grounded in both perspectives. In the next installment I’ll propose some alternative ways forward that do not depend up state determination of individual essence or the inspection of the genitals of children. Surely we can do better.

You will eventually discover that there is no middle ground. Either you support taking sports from females and giving them to male-bodied people, or you support the LGBTAlphabet agenda 110% without exception.

Human reproductive biology is not a construction. You don't call the sunset a "construction," you construct the word "sunset" to mark the phenomenon. The world is made of stuff, not words. We are made of blood and meat and bone, not words. Nature does not give a damn what words we use to mark or describe its properties. Male and female bodies are the result of human evolution as a sexually dimorphic species. No amount of "construction" is ever going to make male bodies in female sports fair, ever.

You will have to choose one or the other. The lines are drawn. You are standing in no man's land -- "neither hot nor cold, I spit you out of my mouth."

Good start to the discussion, Roger.

A major concern of mine is that transgender (male to female) athletes have the advantage of years of elevated male hormones that have built bone and muscle mass. Should they be able to compete with those who have not have this advantage? How would we regard a female who had taken testosterone in her formative years, but was now drug free?