Global climate policy has evolved from an emphasis on reducing risks associated with altering the climate to one focused on seeing global average surface temperature as an indicator of the quality of life on the entire planet that we can fine tune through energy policy.

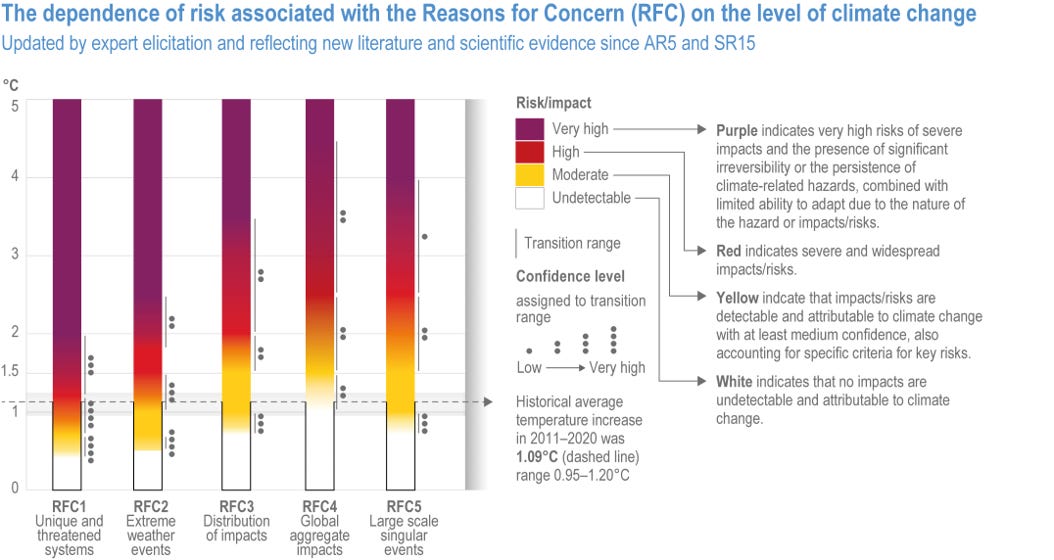

This singular focus is clear in the figure below from the most recent assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR6 WG2 Figure FAQ16.5.1), which summarizes “reasons for concern” about “climate-related hazards” — these include “extreme weather events” and “large-scale singular events.”1

The figure is a bit complicated. It shows five different “reasons for concern” as the shaded bars, with the white parts at the bottom of each bar indicating that at these levels, impacts are “undetectable.” The colors yellow, red and purple indicate successively greater risks and impacts as a function of global temperature on the vertical axis, which goes from zero up to 5 Celsius. Near zero Celsius there are no detectable risks, and as temperatures increase everything quickly gets worse.

The figure is only the latest version of what is called the “burning embers” diagram, which has a 30+ year history. In 2012, Mahoney and Hulme argued that the diagram serves “much like an expressionist painting,” and explained:

“. . . the “burning embers” diagram seeks not to figuratively represent a phenomenon (the changing climate), but rather its intangible effects. These effects, be they heightened levels of danger or risk, are quickly translated into affect through the use of literary and visual conventions such as the emotionally charged colour palette. . .The “burning embers” diagram feeds certain anxieties about the future; we can sense ourselves walking powerlessly into the red heat, a fate made all the more inevitable as the red zone creeps towards the colourless safety of the baseline.”2

There is a lot that we could unpack here about science, politics, belief and the pathological collapse of the climate discourse into the notion that global average surface temperature provides a single, reliable indicator of human well-being and planetary health — what Hulme calls “climatism.”

Today, I’ll pass on those deeper issues and instead take an empirical look at the IPCC’s 1850-1900 “pre-industrial” period that has come to represent a time before climate change — the white parts at the bottom of the “burning embers” diagram. The Paris Agreement’s 1.5C and 2.0C temperature targets are anchored on this period of zero Celsius.

Climate activists claim that every increment of warming over the historical “pre-industrial baseline” results in more harm to people and the planet.3 For instance, upon the recent release of the Fifth U.S, National Climate Assessment, Katherine Hayhoe of The Nature Conservancy and lead author of the report, claimed:

“This report says every 10th of a degree of warming matters. Every bit matters. It clearly shows that per 10th of a degree of avoided warming, we save, we prevent risk, we prevent suffering. And that’s pretty powerful.”

Let’s set aside the fact that we can’t measure global average temperature to 0.1C (e.g., for 2020, the IPCC AR6 provided a 90% confidence range of 0.25C, as you can see in the figure below) or that we have no ability to distinguish climate impacts with any meaningfulness at 0.1C differences.4

One important reason that the period 1850-1900 serves as a useful baseline of climate utopia is that almost no one has any idea what the climate looked like back then, much less the climate impacts actually experienced. Most modern climate records start in the 20th century, and to the extent that the IPCC considers pre-20th climate it is in terms of physical quantities and not impacts or risks (e.g., as in the figure immediately above). Most attention these days in climate research is focused far into the future through the lens of climate models — there are very few old school Changnons, Lambs, Kelloggs and Diazes left in the climate community.

Over the past few weeks I have read Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, by Mike Davis. During my time as a scientist at the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research in the late 1990s and early 2000s, I spent a lot of time researching impacts of and responses to El Niño and La Niña under the guidance of the one and only Mickey Glantz. I was aware of the 1877-78 El Niño event and its profound impacts, but I never connected its significance to the contemporary climate discourse until recently.

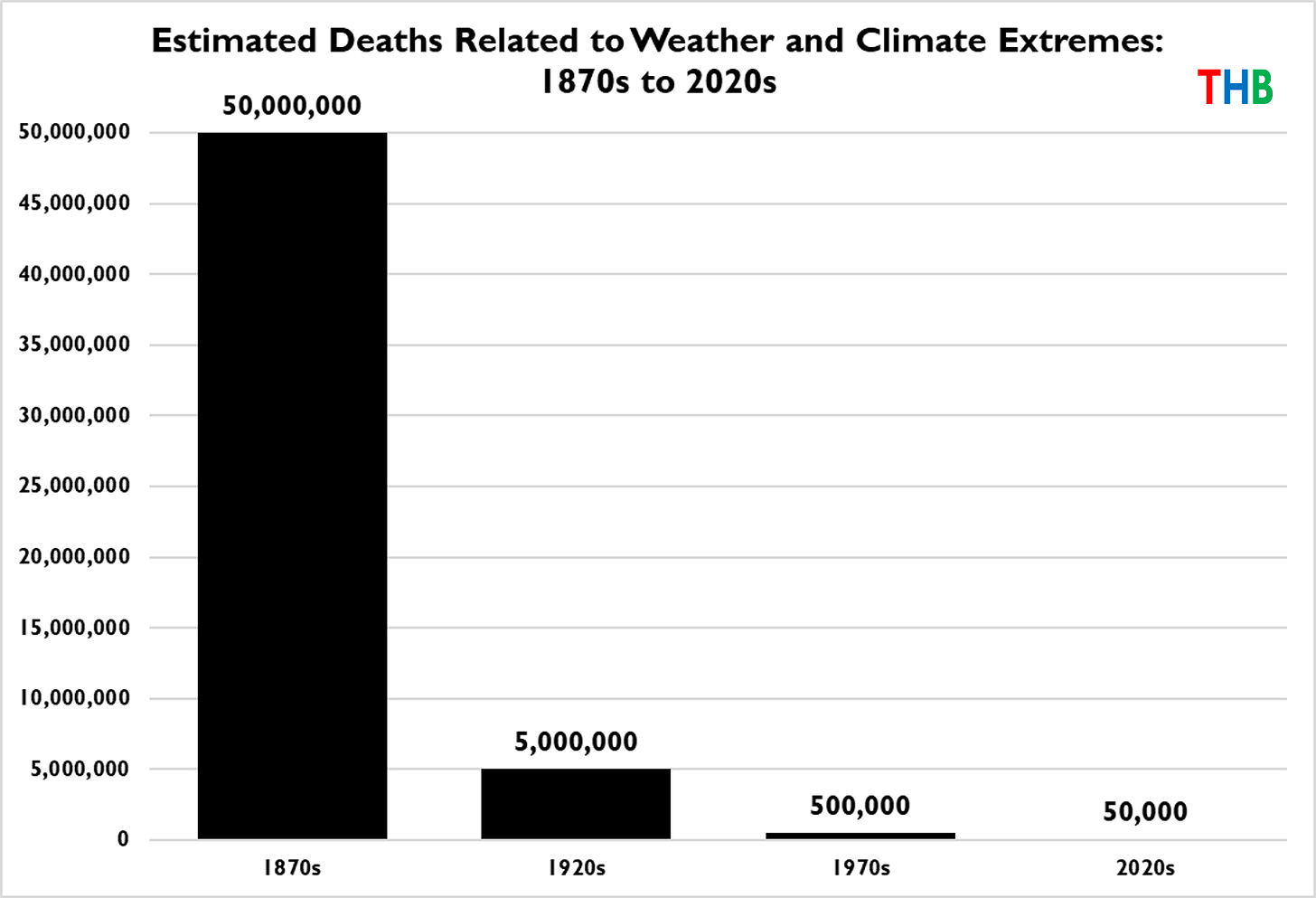

Davis compiles estimates suggesting that more than 50 million people died in the mid-1870s related to extreme weather and climate — That equates to about 4% of global population. Today, that same proportion of the world’s population would be over 320 million deaths, or almost the entire population of the entire United States. We cannot even imagine this magnitude of human suffering.

The proximate cause of the 1870s massive climate impacts was a very strong El Niño event in 1877 and 1878, but that event was also perhaps comparable to strong El Niño events in 1997/98 and 2015/16. What accounts for the massive loss of life in the 1870s? Davis explores this in depth, and the simple answer is colonial rule informed by Malthusian impulses.5

For instance, Davis quotes Sir Evelyn Baring, UK finance minister at the time, who justified the unwillingness of the British Empire to ameliorate the impacts of drought on its subjects in explicit Malthusian terms:

“[E]very benevolent attempt made to mitigate the effects of famine and defective sanitation serves but to enhance the evils resulting from over-population.”6

The U.K.’s 1878-1880 Famine Commission concluded:

“The doctrine that in time of famine the poor are entitled to demand relief … would probably lead to the doctrine that they are entitled to relief at all times, and thus the foundation would be laid of a system of general poor relief, which we cannot contemplate without serious apprehension …”7

The figure below shows estimated decadal deaths related to weather and climate extremes for four decades, each separated by a half century, starting with the 1870s.

Beyond the massive impacts associated with the 1877/1878 El Niño, there were also many other extreme events with impacts well beyond those of recent times, such as the Great Midwest Wildfires of 1871 which killed as many as 2,400 people, the 1872 Baltic Sea flood, a 1875 midwestern U.S. locust swam of an estimated 12.5 trillion locusts, the 1878 China typhoon that killed as many as 100,000 people, and the U.S. experienced 6 landfalling major hurricanes in the 1870s, compared to just 3 in the 2010s.8

This cursory overview of various events of the 1870s indicates that notion that the period 1850 to 1900 was somehow safer or less extreme in terms of climate extremes and impacts is simply false. If the weather gods offered me the opportunity to replay over the next decade the weather and climate of the1870s, instead of the uncertain future before us, I’d take the uncertain future for sure. The 1870s were one of the most extreme climatic decades in modern human history.

Of course, the impacts of weather and climate are much more a result of our collective adaptive capacity, including technology, policy and overall societal wealth. Whatever the weather and climate future holds in store for us, we are collectively much better prepared to deal with it than we were 150 years ago.

A careful look at history tells us that the global average surface temperature is not a control knob that we can set to a preferred value to “prevent suffering.”

Thanks for reading! I hope you are having a wonderful holiday season. We have a white Christmas here in Colorado and lots of time with friends and family. THB is a group effort and supported by you — with your participation, sharing and subscriptions. Look for the 2024 Home Office Pool coming later this week. Meantime, comments, questions, critique and discussion are all invited and welcomed.

Don’t forget that the IPCC uses a broader definition of “climate change” than does the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change. Specifically, the IPCC defines climate change as, “A change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer. Climate change may be due to natural internal processes or external forcings such as modulations of the solar cycles, volcanic eruptions and persistent anthropogenic changes in the composition of the atmosphere or in land use.”

See also Mahoney 2015.

Contrast this belief with Mike Hulme’s view, one which I agree with: “[T]here are some futures beyond 1.5 degrees C (or even 2 degrees C) that are more desirable than other futures which do not exceed these warming thresholds. We should not mistake one set for the other.”

It is not clear that we can distinguish climate impacts even at much larger differences — except in a hand-wavy sort of way. Global average surface temperatures are an integrated outcome — it is weather and climate in specific places that influences outcomes. It is one thing to say that altering the Earth’s energy balance increases risks, it is quite another to precisely identify and predict how those risks manifest in certain times and places.

The history related by Davis is incredibly troubling, and “late Victorian holocausts” is an apt descriptor.

Think about this quote in the context of the modern reluctance of some to support fossil fuel development in energy-poor regions because of their contributions to climate change.

This quote reminds me of recent debates over “loss and damage.”

It would be a worthwhile research project to systematically assess the global climate anomalies and extreme events of 1850 to 1900.

Thanks for adding this. I knew that periodic crop failures and resulting famines in Scandinavia were a key part of my family history. One such weather driven event wiped out 7 of 8 members of my family. I’m descended from the sole survivor. Not the good old days!

Thanks Roger that was fascinating. I had no idea but somehow I am not surprised. Watching films about that era shows clearly how vulnerable the population was to all sorts of calamity. That article is one of my favorites to date. Happy New Year.