This is a guest post by Dr. Volker Hahn, a science journalist and a science communication expert in Leipzig, Germany. He has a Ph.D. in biogeochemistry from the Friedrich Schiller University Jena. Volker is employed by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) where he serves as the Head of Media & Communications. This review is written in his personal capacity. You can follow Volker on the platform formerly known as Twitter @volkerhahn1.

In a recent post at The Honest Broker, Roger Pielke Jr. asked what would happen if we “just stop oil” – as a campaign group of the same name demands. The answer he gave is that if it were possible (it is not), it would cause immense societal disruption, suffering and death. Such calls, while drastic, are not isolated incidents; instead, they are extreme manifestations of what Mike Hulme calls “climatism”.

According to Hulme, climatism is:

“the ideology – the settled belief – that the dominant explanation of all social, economic and ecological phenomena is a human-caused change in the climate. Complex political, socio-ecological and ethical problems and challenges come to be regarded as only being solved or adequately dealt with by first arresting the human causes of changes in climate.“

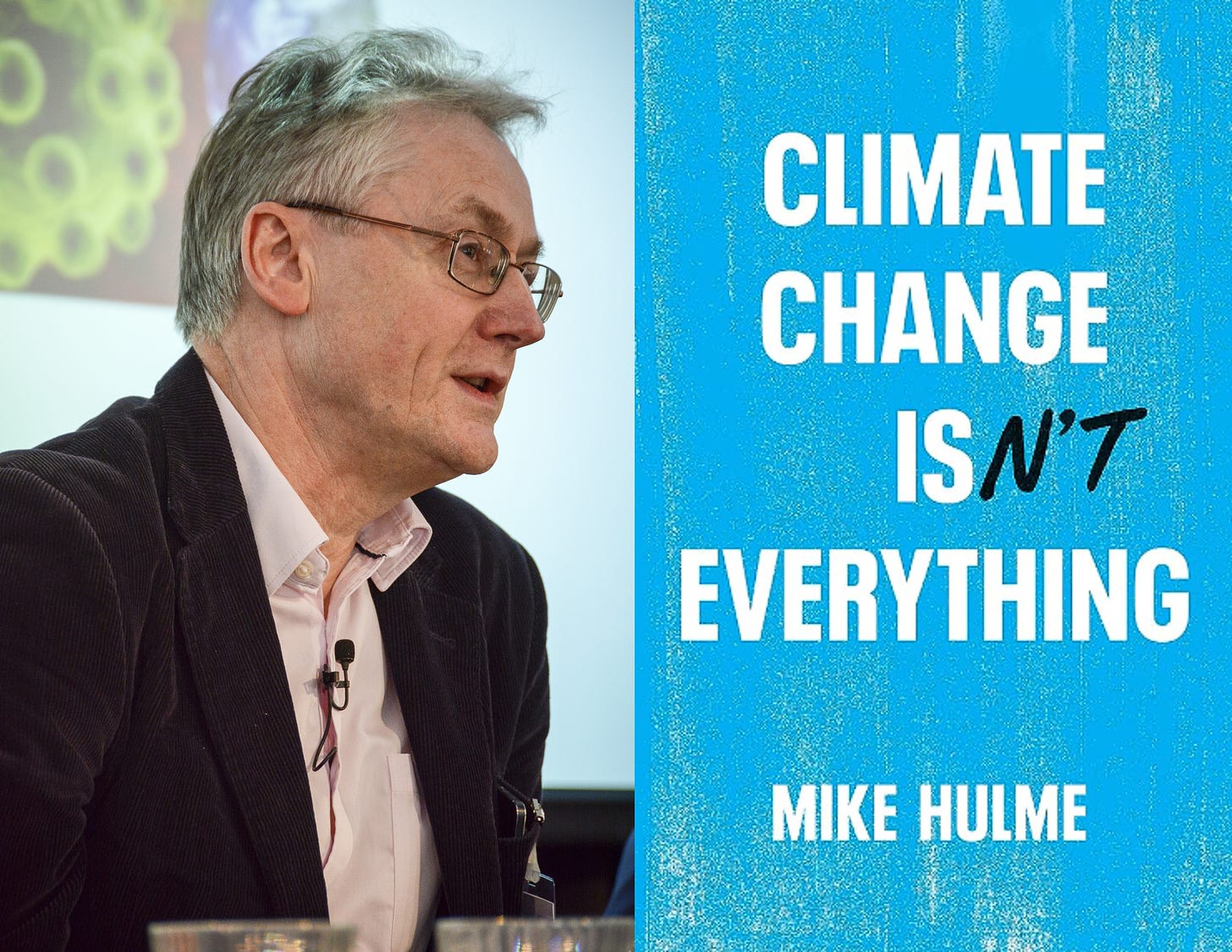

The concept of climatism is at the center of Hulme’s new book, Climate Change Isn’t Everything: Liberating Climate Politics From Alarmism (Polity, 2023, 208 pages).

Mike Hulme is professor of human geography at the University of Cambridge and has long been a prudent voice in the climate discourse. In an influential paper from 2011, Hulme introduced the term “climate reductionism”, the idea that climate alone would dominate the human future. Climatism, according to Hulme, grows out of climate reductionism but reduces not only the future to climate but also the present:

“The problems facing the world – whether the triumph of the Taliban, the management of wildfires, Putin’s war in Ukraine, the movement of people – all become ‘climatized’.”

Hulme dedicates an entire chapter to meticulously dissecting how climatism has arisen over decades. He identifies ten developments, which he calls “moves”. Climate reductionism is one of them (move 5), but not the most important. This is, according to him, the adoption of global temperature as a “flawed index for capturing the full range of complex relationships between climate and human welfare and ecological integrity” (move 3). The ten moves, Hulme says, have enabled the ideology of climatism to arise and climate change to emerge as the “leitmotif of contemporary politics.”

This, of course, raises the question of how climatism could become so successful. A major merit of Hulme’s book is that it provides a set of convincing explanations, laid out in chapter “Why is Climatism So Alluring?”

If Hulme's readers concede that the issue of climate change involves more ambiguity than perceivable in the public discourse, then this book will have served a purpose.

One of Hulme’s answers to this question is climatism’s power as a “totalizing master-narrative”. A narrative that is easy to understand and that brings clarity and simplicity to a complex world. This narrative typically bears an apocalyptic, mesmerizing tone:

“when confronted with nature’s irresistible power, the consequent feelings of awe, terror and danger exert an irresistible pull on the human imagination. In spite of the danger, we find ourselves enraptured, captivated by the forces of nature. We are fascinated by the frisson of vulnerability, destruction and death.”

Hulme draws parallels to other catastrophic parables like the ancient myth of Gilgamesh (Noah’s flood) or Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which appeal to a receptive audience, not least by pointing “to moral degeneracy, selfish greed or technological hubris”. This points to another alluring facet of climatism: Dividing the world into two camps, framing climate change as a battle between good and evil. “If you are not in resistance you are appeasing evil,” write Just Stop Oil on their website. Alfred Hitchcock knew: “The more successful the villain, the more successful the picture.”

Yet another aspect that allures people to climatism is that it borrows its authority from science. Since climatism rests on “special knowledge” provided by science, the thinking goes, it must be true, reliable, and ultimately non-negotiable, says Hulme.

Hulme discusses the role of science and scientists in a separate chapter (“Are the Sciences Climatist?”). Among other things, Hulme criticizes the use of implausible and outdated climate scenarios, citing Pielke Jr. At The Honest Broker, you can find several posts on this issue and on the role of scientists engaging in climate advocacy (e.g., here and here).

Yet, where is the problem? Isn’t climate advocacy serving a noble cause? And may some hyperbole be a good thing after all?

“If the ideology of climatism posed no dangers, then my argument thus far might be interesting, but not particularly important. But the next chapter seeks to persuade you that there are some real dangers with this way of thinking.”

The chapter “Why is climatism dangerous?” is one of the strongest in Hulme’s book. Of course, as for all other chapters, I can only provide a brief selection of his arguments.

According to Hulme, climatism can lead to real-world consequences caused by a “narrowness of vision”. As an example, Hulme explains how the EU Biofuels Directive from 2010, designed with a well-meaning but myopic focus on climate, has destroyed biodiverse forests and dispossessed people of their livelihood. Not in Europe but in Southeast Asia and South America, where palm and soy are grown to satisfy Europe’s hunger for biofuels.

Climatism’s psychological implications may also cause harm. Hulme argues that hyperbole, doom and gloom may not motivate action after all but induce anxiety and disengagement.

Hulme’s book may not deliver radically new or surprising insights. But it is a concise digest of the current climate discourse and depicts where things are going wrong. Hulme is a skillful writer; his lines of thought are clear, his language intelligible. Hulme makes a strong case for recognizing climate change as a “wicked problem”, unsolvable with a simplistic and totalizing master-narrative that puts climate above everything else. But: “If Not Climatism, Then What?” asks Hulme in the book’s penultimate chapter.

Not surprisingly, Hulme does not propose a simple solution, no silver bullet for solving all problems associated with climate change. “Wicked problems need clumsy solutions,” he argues. This thinking is reflected in five “antidotes”, which Hulme proposes as correctives against climatism. They involve, amongst others, foregrounding scientific uncertainty, defusing deadline-ism, and acknowledging the plurality of values and goals as, for instance, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals:

“To quote Otto von Bismarck: ‘Politics is the art of the possible, the attainable – the art of the next best.’ I believe climate pragmatism, not climatism, offers the best way for cultivating such an art.”

Most climate activists would probably disagree. Hulme anticipates likely objections against his theses and defends them in advance. This is what the last chapter is about (“Some objections – ‘You Sound Just Like …’”). Hulme seems to be going on the defensive without need. But it does make sense. While he will certainly not convince those entrenched in the climatism camp, this final chapter serves as a critical revision of Hulme’s assertions – a worthwhile exercise for the reader, who might be sympathetic to some of these objections.

Again and again, in his book, Hulme stresses that he is not dismissing the reality or the importance of climate change. Of course, such disclaimers will not save him from being accused of appeasing evil or from being called names. Hulme sure has no illusions about this, Manichean thinking being one of climatism’s characteristics.

But no need to side with or turn away from Hulme altogether. One need neither agree with nor disagree with each and every one of his claims. If Hulme's readers concede that the issue of climate change involves more ambiguity than perceivable in the public discourse, then this book will have served a purpose.

Thanks for reading THB! I plan on offering more guest posts as THB continues to evolve — and I plan on inviting thoughtful writers from a diverse range of perspectives. I am happy to hear your suggestions. Guest voices here at THB — like everything here— are made possible thanks to your support. Please like and share this post, and your comments and discussion are invited. Please consider a subscription at any level! Have a great week. —RP

I’d add on that climatism has an interesting sociology of science effect: it honors the atmospheric scientist over the humble agricultural scientist or petroleum geologist or wildlife biologist; it honors abstractions over observations (what I call asking Nature a question and not waiting around for the answer), modeling and satellite imagery over on the ground measurements, and the endless stream of predicting bad things without involving the scientific fields that have historically worked with past problems and solutions. Social scientists keep pointing out the problems of top-down research, say on biodiversity conservation prioritization without involving local people, and yet journals keep churning out papers that purport to tell us about “the world’s climate” or “the world’s biodiversity.”

Historians of science may recognize the 19th century class bias of “purer” science vs. applied.. regular historians may look at this as a form of scientific colonialism.. And so science prioritized and designed by scientists.. by the scientists of the scientists and for the scientists, as it were, continues on. Would we have to be so internationalized if not for abstractions like climate or biodiversity? Is that just an excuse for busy-body scientists to tell others what to do? As we have seen forests are now “too important for climate” to be left to the likes of forest scientists; and agriculture now has Scientists Who Know Better at Stanford and Yale. Climatism, like scientism, is way too convenient for those who Think They Know Better to avoid the rough and tumble of democracy.

Thank you, Roger. Guest articles like this are a nice addition, and hopefully will take a little pressure off you to produce content, giving you some much needed time for research which we all will eventually benefit from.