What the media won't tell you about . . . Tornadoes

Let's take a look at what the data and science actually say

Your support enables me to conduct these deep dives into climate science and policy as an independent researcher. Please consider a subscription at any level. And please share widely. Thank you!

This is the latest post in an ongoing series, titled “what the media won’t tell you about . . .”, which is motivated by the apparent systemic inability of the legacy media to play things straight when it comes to extreme weather and disasters. Climate change is real and important, but its importance is not an excuse for the pervasive climate misinformation found across the legacy media.

Here are the previous installments in the series, which are among my most popular posts and which have gone unchallenged.

What the media won’t tell you about . . .

Today’s post focuses on U.S. tornadoes. This year so far has seen a lot of tornadoes — 178 were reported through February 11th, the 2nd most since 2005 and well above the 2005-2022 mean of 66 to date. Of course, nowadays wherever there is extreme weather, journalists rush to claim a connection to climate change no matter what the science actually says. For instance, after a tornado outbreak last month, the Associated Press reported that the tornadoes had been “juiced by climate change.” Similarly, The Washington Post said that in the past it was difficult to tie tornadoes to climate change but now, “science is accumulating to support the linkage.”

Neither reported any of the data and science I share below. So, let’s take a look.

Tornadoes are classified by their intensity according to the 6-category Enhanced Fujita (EF) Scale, which runs from 0 to 5, and is shown in the table above (alongside the original Fujita Scale). The U.S. National Weather Service (NWS) explains that “The Enhanced F-scale still is a set of wind estimates (not measurements) based on damage.” You can read about the EF Scale and its history here and here.

In a 2013 paper, Kevin Simmons, Daniel Sutter and I used the EF Scale in a set of normalizations of U.S. tornado damage from 1950 to 2011 to account for changing wealth, population, and housing. You can see a recent update of our analysis through 2021 in the figure below and discussed in some detail here.

In performing our analysis of normalized U.S. tornado losses, we had to navigate the changing approaches used by the NWS to classify tornado strength from 1950 and various “oddities” of the dataset. See our paper (linked at the bottom) for an in-depth and technical discussion of these issues and how we dealt with them.

Across our normalization approaches and NWS classification methods we found that from 1950 to 2011, tornadoes of EF3 strength or greater — accounting for about 6% of all reported tornadoes — were responsible for almost 70% of total damage. Here are the numbers for even stronger tornadoes:

EF4+ tornadoes are about 1.2% of tornado reports and account for about 44% of damage;

EF5 tornadoes are about 0.1% of tornado reports and account for about 14% of damage;

According to The Tornado Project, from 1950 to 2011 EF4 and EF5 tornadoes were responsible for about 67% of all deaths from tornados.

In short, about 70% or more of the death and destruction from tornadoes results from less than 7% of all reported tornadoes — those of EF3 strength or greater.

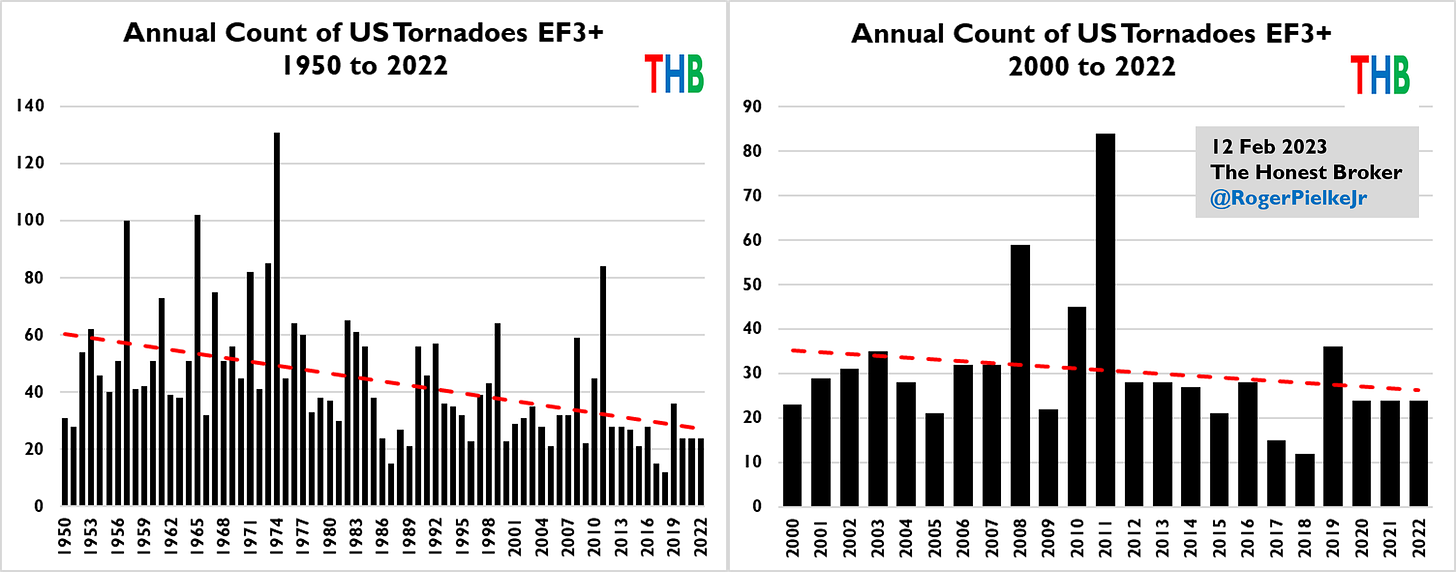

Let’s take a look at trends in EF3 and stronger tornadoes, using official data of the NWS Storm Prediction Center. These data can be seen in the figures below.

The panel on the left shows reported EF3+ tornadoes from 1950 to 2022 and it indicates a dramatic decline, from about 60 per year to about 30. The figure on the right shows the same data for 2000 to 2022, also indicating a decline in incidence over the more recent period.

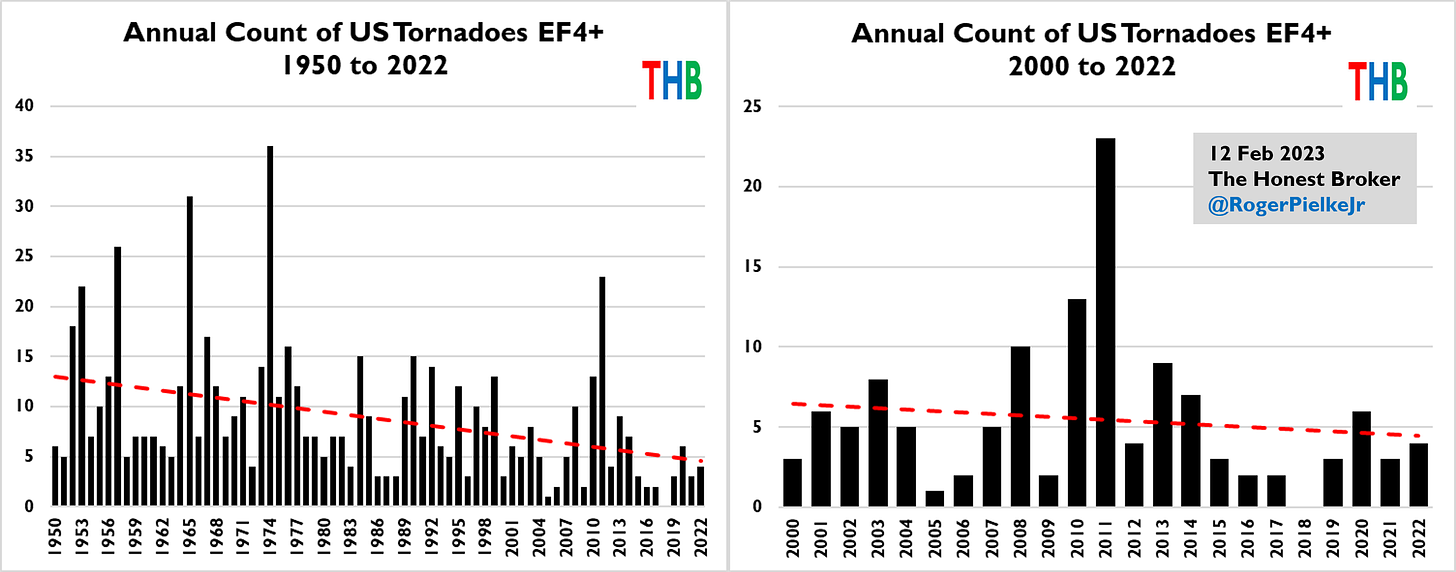

Let’s now look at EF4+ tornadoes.

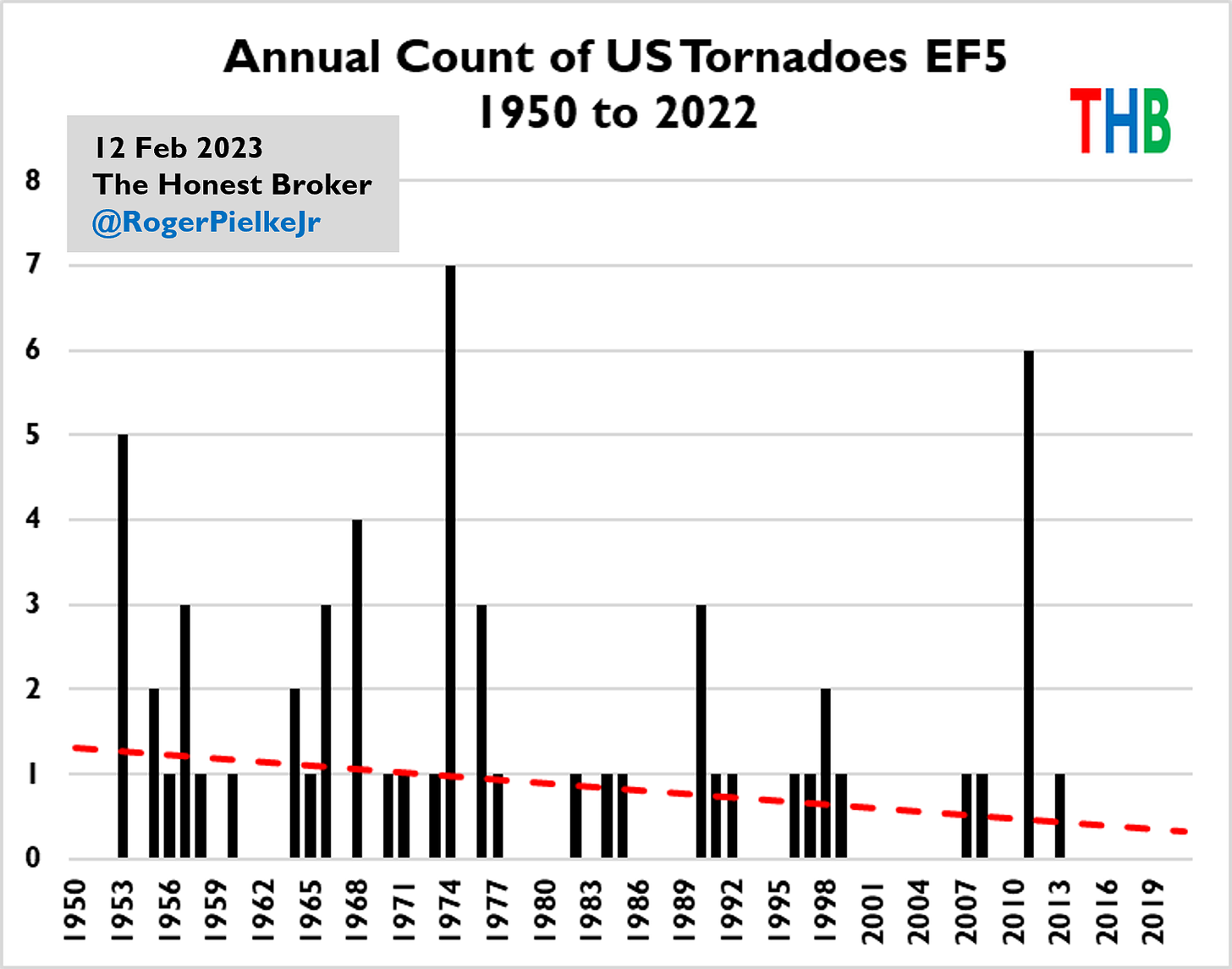

Here we also see declines over the longer (1950 to 2022) and more recent (2000 to 2022) periods. For completeness, let’s also look at the very rare EF5 tornadoes.

Tornadoes of EF5 strength are today rare, with almost 10 years since the last such event was reported in May, 2013. However, 2011 saw 6 such tornadoes in just one year. Here as well the official data indicate a long-term decline.

The data consistently indicate a long-term decline in major tornado incidence on long- and near-term time scales. But are these trends real, or are they an artifact of changing methods for collecting data on tornado incidence?

This is a question that we addressed directly in our research on normalized tornado losses. We concluded:

The normalized results are also suggestive that the long-term decrease in reported tornado incidence may also have a component related to actual, secular changes in tornado incidence beyond reporting changes. To emphasize, we do not reach any conclusion here that stronger that ‘suggestive’ and recommend that this possibility be subject to further research, which goes beyond the scope of this study.

While there are greater uncertainties in tornado counts prior to the deployment of Doppler Radar in the 1990s, we can have strong confidence that major tornado incidence so far this century has decreased. It may be that this recent trend reflects a longer-term decrease in activity. The case for a long-term decrease in strong tornadoes is stronger today than when we first suggested it in our 2013 paper.

There has also been recent research on changing spatial and seasonal trends in tornado incidence (from 1979 to 2017), that finds that in recent decades activity has shifted east from the Great Plains to the Southeast. That research is explicitly equivocal on attribution:

At this point, it is unclear whether the observed trends in tornado environment and report frequency are due to natural variability or being altered by anthropogenic forcing on the climate system.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in its most recent report did not spend much time on tornadoes and none at all on trends in strong tornadoes. It concluded that any observational trends in tornadoes “are not robustly detected.” The data and research I have shared here would seem to contradict that conclusion — both in terms of the frequency of major tornadoes and their geographic and seasonal activity. However, there is strong agreement that major tornado activity has not increased, and no trends have been claimed to be attributed to climate change.

Here is the bottom line:

Strong U.S. tornadoes — the ones that cause the most death and destruction — have certainly not increased since 1950;

In fact, evidence suggests that they may likely have decreased in frequency since 1950, perhaps by as much as 50%;

It is almost certain that major tornadoes have decreased this century, by about 20%;

The U.S. has not seen an EF5 tornado in almost 10 years, the longest such streak since at least 1950;

The geography of tornado incidence shifted eastward from 1979 to 2017, but no strong claims or mechanisms of attribution have been advanced;

Both inflation-adjusted and normalized tornado damage has decreased in the U.S. since 1950, providing good support and consistency for claims that overall incidence of strong tornadoes has decreased;

Tornadoes are not being “juiced” by climate change.

Looking to the future, a recent paper helps to place things into important perspective:

“the impacts associated with projected 21st century increases in tornado frequency are outweighed by projected growth in the human-built environment”

Climate change is part of a popular narrative associated with extreme weather. However, future impacts on people will be determined much more by what we build, how we build, where we build alongside with disaster preparation, including forecasts, warnings and response.

Let me end this post with a shout out to the fantastic people at the National Weather Service and especially (for this post) the Storm Prediction Center whose work not only saves many lives every year, but their time-intensive and meticulous collection of data on tens of thousands of tornadoes over many decades allows work like mine. Thanks NWS & SPC!

Below, for paid subscribers please find a PDF of our paper on normalized U.S. tornado damage.

Thanks for reading, sharing and subscribing!