SERIES: What the media won't tell you about . . . hurricanes

Let's take a look at what the IPCC and official data really say

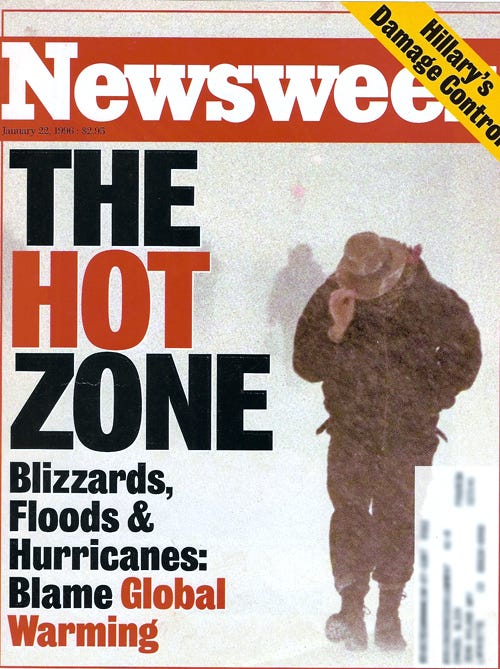

In January, 1996 I was a post-doc at the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research doing research on hurricanes and floods. One day that month my boss, the incredible Mickey Glantz, came into the office with a copy of Newsweek, with the cover announcing: “THE HOT ZONE Blizzards, Floods and Hurricanes: Blame Global Warming” (below). Mickey tossed me the magazine and said, “this is interesting, why don’t you have a look.” So I took a look, and over the 26 years since have been studying climate, hurricanes, and their impacts. In this short post, on the first day of the official Atlantic hurricane season 2022, I’ll share five points of consensus science on hurricanes that seem to be systematically ignored by the media, and especially by those on the climate beat.

1. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in its latest report, concluded that there remains “no consensus” on the relative role of human influences on Atlantic hurricane activity.

Here is what the IPCC says exactly:

“[T]here is still no consensus on the relative magnitude of human and natural influences on past changes in Atlantic hurricane activity, and particularly on which factor has dominated the observed increase (Ting et al., 2015) and it remains uncertain whether past changes in Atlantic TC activity are outside the range of natural variability.”

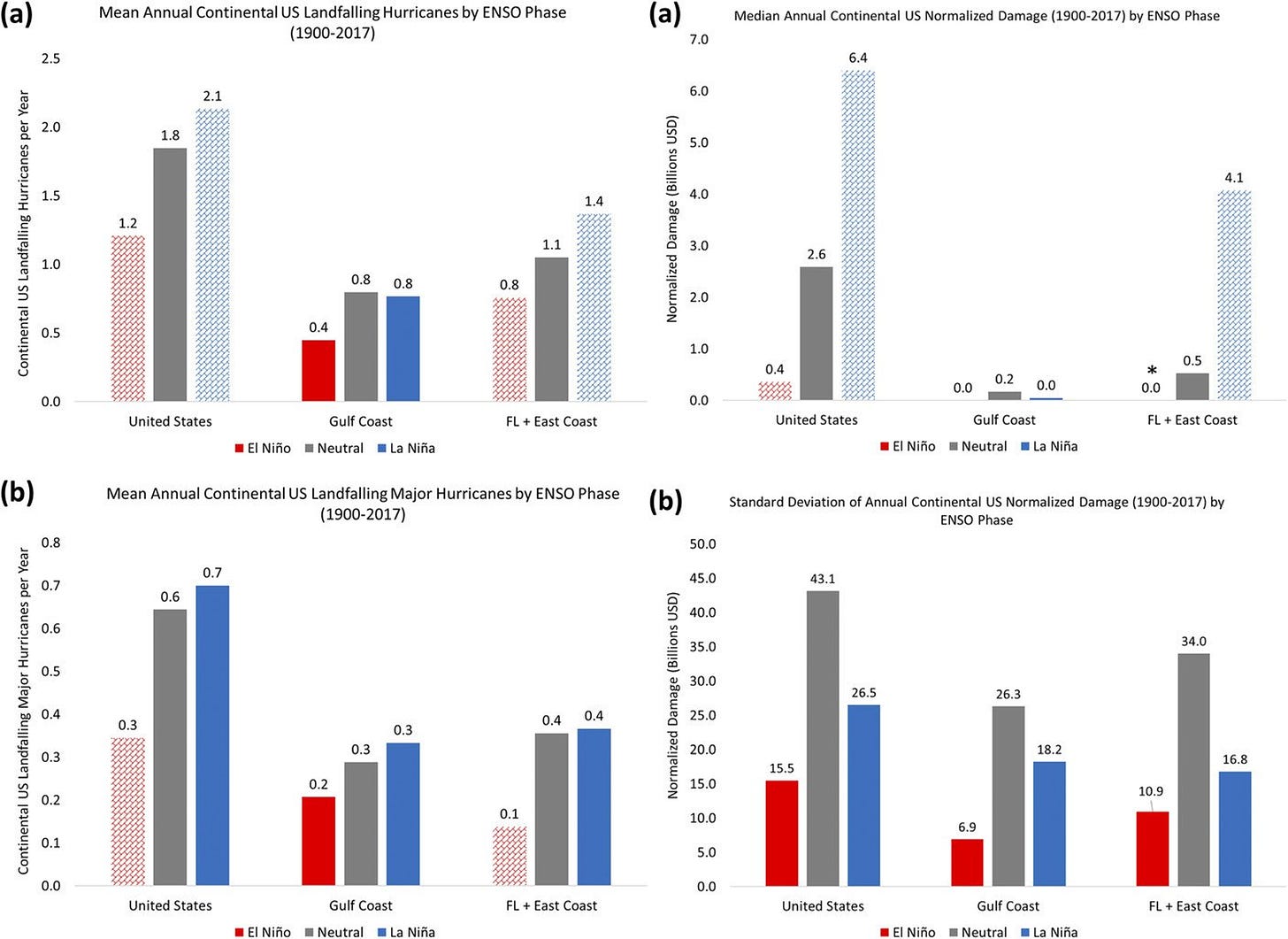

One reason for the inability to unambiguously attribute causality to Atlantic hurricane activity is the large interannual and interdecadal variability. The figure below comes from one of our recent papers and it shows the large variability in U.S. mainland hurricane landfalls and damage based on the state of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). There are more than 2x the median landfalls during La Niña than in El Niño and 16x the median damage — this relationship holds for the basin overall as well. We are currently in a La Niña phase, so watch out!

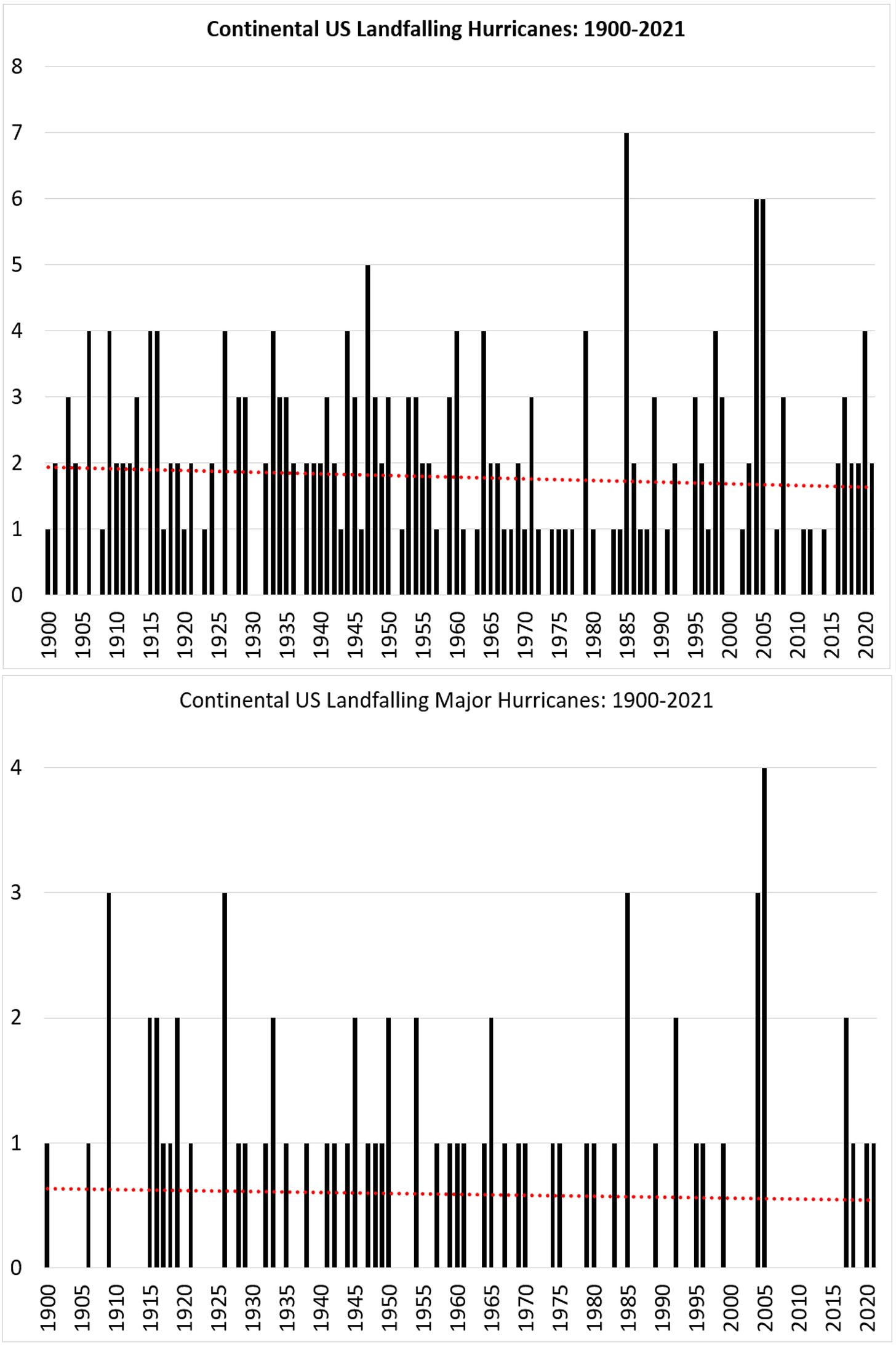

2. The IPCC has concluded that since 1900 there is “no trend in the frequency of USA landfall events.” This goes for all hurricanes and also for the strongest hurricanes, called major hurricanes.

Below are official data on continental U.S. hurricane landfalls, updated through 2021 from our recent paper. If you think that there have been a lot of major hurricanes in recent years, you’d be correct. One reason for the near-term increase in activity is an incredible unprecedented 11-year period from 2006-2017 during which no major hurricane made CONUS landfall. Recent years are more typical of patterns seen during the 20th century. So for those who come to the climate beat during the past twenty years, it would be easy to think that we didn’t used to have hurricanes and now we do. This is a good example that illustrates why trying to see climate changes with your own eyes is never a good substitute for data and applied climatology.

The data in the two graphs above have never been presented in IPCC or U.S. National Assessment reports, and I cannot recall ever seeing it in major media reporting on climate change (though I am happy to be corrected). One might think that such basic information might be of broad interest.

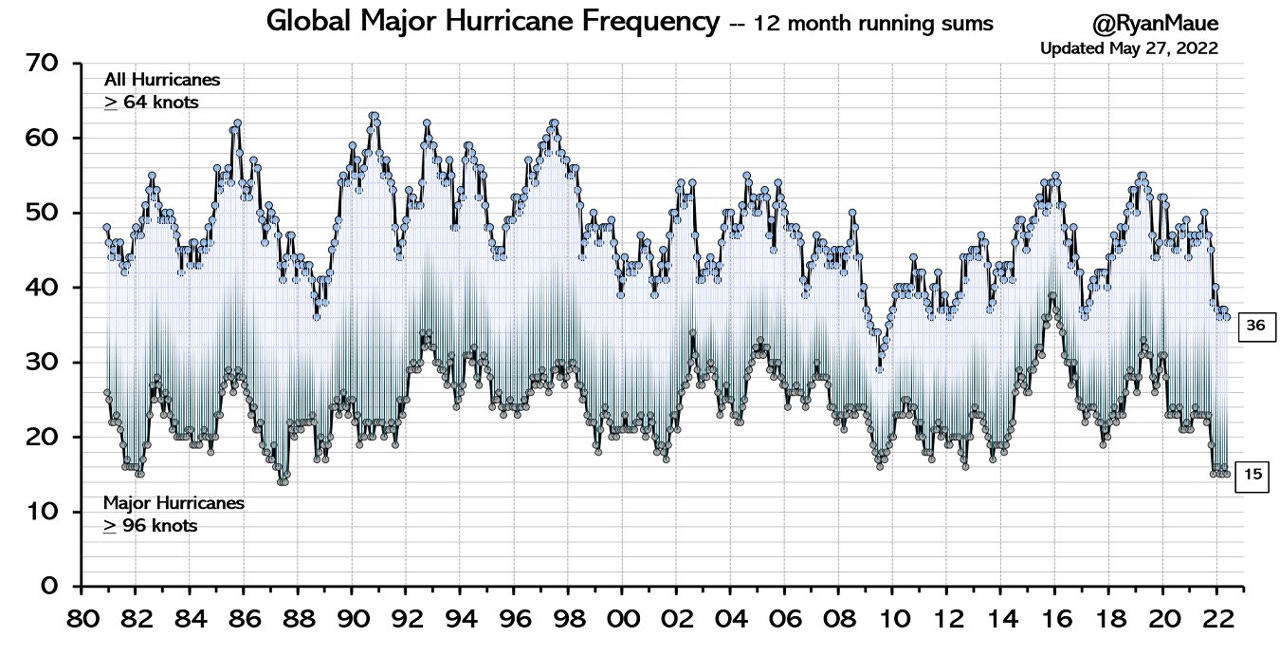

3. Continental U.S. landfalls are just a small proportion of all North Atlantic hurricanes, which in turn are just a small proportion of all global tropical cyclone activity. Since at least 1980, there are no clear trends in overall global hurricane and major hurricane activity.

You can see trends (or more precisely, the lack of) in the global occurrence of tropical cyclones at hurricane and major hurricane strength (12-month sums since 1980) in the figure below, courtesy @RyanMaue. A little-known fact is that the past 12 months are very close to a 42+ year low in the numbers of major hurricanes on planet Earth (note that “hurricanes” are what “tropical cyclones” are called in the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific, they are the same phenomenon).

4. There are many characteristics of tropical cyclones that are under study and hypothesized to be potentially affected by human influences (including but not limited to greenhouse gas forcings). These include tropical cyclone rainfall intensity, speed of storm movement, latitude of storm formation, pace of intensification, length of seasonality and many more. You can easily find different studies and different scientists with contrasting views on the role of human influence on tropical cyclones, but at present, there is not a unified community consensus on these hypotheses, as summarized by the World Meteorological Organization in several recent expert assessments (see the end for links).

Human-caused climate change is of course real and requires vigorous implementation of adaptation and mitigation policies. And of course it is entirely plausible that human influences have had and will have detectable and attributable effects on tropical cyclones. However, if you elicit the views of tropical cyclone experts — as the World Meteorological Organization did recently — you will find a very wide range of views on current states of understandings. The importance of a subject, regrettably, does not compel certainties.

For instance, on the question whether the most intense tropical cyclones will increase worldwide due to greenhouse gas forcing, expert views range widely, from low confidence to high confidence, with many arrayed in between. And if you look across model results, is even plausible under a range of scenarios that tropical cyclones become less frequent and/or less intense. A diversity of legitimate understandings is of course OK — this is how science often works in many areas. If the topic were simple, we wouldn’t need much science.

With hurricanes often placed front and center as the most visible manifestation of climate change, accurate representation of the current, complex state of understandings can be difficult. Can you find an expert or a study to confirm whatever you want to believe on hurricanes? Sure you can — the topic is a cherry-picker’s dream. And I see advocates and polemicists feasting on cherries all through hurricane season.

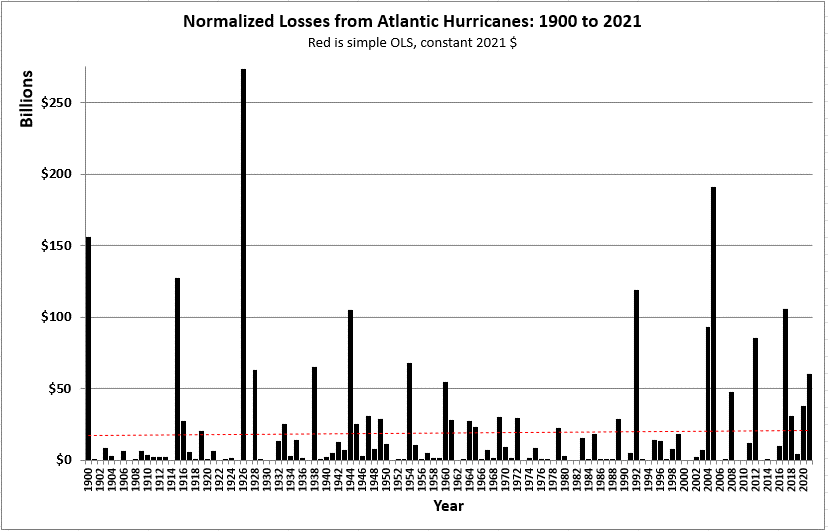

What we can say with a very high degree of certainty is that the damages from tropical cyclones (both in the U.S. and globally) have increased dramatically over the past century. It is also highly certain that the main reason for this is the ever-increasing amount of wealth we place in their path. The figure below shows the estimated damage from U.S. hurricanes assuming that each hurricane season took places with levels of development of 2021, updated from another of our recent papers.

The data show no upwards trend in damage, which is exactly what we should expect given that there is also no upward trend in hurricane or major hurricane landfalls. Even though there are many aspects of hurricanes past and future that are unknown, uncertain or contested, there is a lot that we do know, but rarely discuss.

5. Hurricanes are common, incredibly destructive and will always be with us. Even so, we have learned a lot about how to prepare and recover.

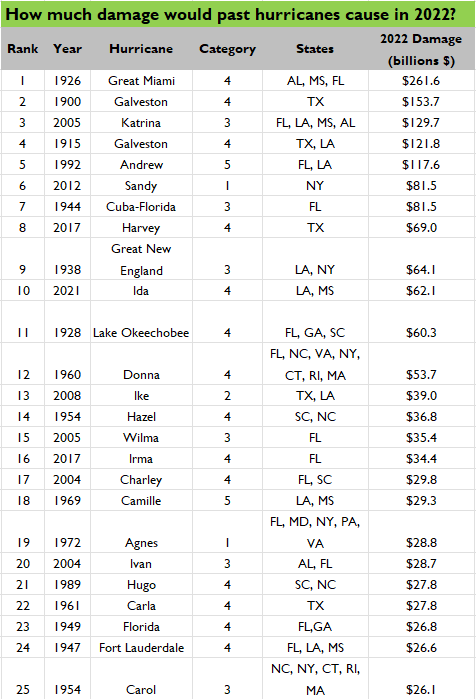

The table below show damage estimates for individual storms, were they to make landfall in 2022, updated from this paper.

You can see that while a few storms of the past decade make it into the top 25 of loss events, there are many storms from the distant past which would cause much more damage., were they to occur today. That means your and my lived experience cannot capture the realities of hurricane disasters. We don’t need climate change to understand that much greater hurricane disasters are possible, just a sense of history.

With each storm comes lessons and opportunities to better prepare for future inevitable landfalls, regardless what the climate has in store for us. Indeed, policy responses to tropical cyclones — in the U.S. and around the world — are one of the great unheralded success stories of science, technology and policy of the past century. To continue, we need to be ever vigilant as successes don’t happen automatically.

It is important for people to understand that what has been observed in terms of hurricane landfalls and losses of recent years is fairly typical of what has been seen over the past century. Whatever climate signals scientists might tease out of the historical records, the impact of hurricanes on society is overwhelmingly determined by how we build, where we build, what we build, what we place inside, and how we warn, shelter, evacuate, recover and so on. That is in fact good news, because it tells us that the decisions we make (and don’t make) will determine the hurricane disasters of the future.

So sure, go ahead and debate and discuss the past and future effects of climate change on hurricanes. Pick cherries if you must. But never lose sight of the fact that the decisions we make every day will determine the impacts from hurricanes that we experience in the future.

For further reading

IPCC AR6 WG1 on extreme events (link)

Klotzbach, Philip J., et al. "Continental US hurricane landfall frequency and associated damage: Observations and future risks." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 99.7 (2018): 1359-1376. (link)

Knutson, Thomas, et al. "Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment: Part I: Detection and attribution." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 100.10 (2019): 1987-2007. (link)

Knutson, Thomas, et al. "Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment: Part II: Projected response to anthropogenic warming." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 101.3 (2020): E303-E322. (link)

Weinkle, Jessica, et al. "Normalized hurricane damage in the continental United States 1900–2017." Nature Sustainability 1.12 (2018): 808-813. (link)

Thank you. I enjoy reading your posts. Your article arrived in my email about the same time as this NASA press-release for <https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-scientists-available-for-2022-hurricane-season-interviews>. I wonder sometimes if we exist in two realities simultaneously? Quoting from the NASA release...

“Along with millions of Americans, I know firsthand the devastation caused by hurricanes. These climate-related events are growing more frequent and powerful, underscoring the need for greater action to improve our nation’s response and resilience to hurricanes,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. “Addressing and mitigating the effects of climate change like hurricanes are at the core of NASA’s mission. From the agency’s upcoming TROPICS mission that will help scientists understand the factors driving storm intensification and contribute to weather forecasting models, to the creation of the Earth Information Center to ensure game-changing NASA climate data is accessible and understandable to decision-makers, NASA will continue to help communities better prepare for and recover from these weather events.”

Thanks for your thoughful and even handed presentation of data. I attended a conference where a group of ex NASA scientists who had been heavily involved in tracking hurricanes and other weather data for the space program. They discussed the fact that until there was radar tracking by aircraft and then satellites a lot of the smaller tropical storms (hurricanes) were not reported unless a ship were in the area. There was also a range issue with the aircraft monitored tracking (The US aircraft only had enough fuel to go ~ 1/2 way over the Atlantic. They showed data that compared before and after years, the amount of small storms and the tracks of storms across the Atlantic. They made a very compelling case that before satellite tracking the Eastern Atlantic probably had a large number of storms which were not counted. They showed a map of a year in the 20s or 30s that showed almost zero storms counted that were beyond the aircraft range, and they compared that to a post satellite year that showed a large number of small hurricanes in that Eastern Atlantic area. Could you please comment on that observation.