SERIES: What the media won't tell you about . . . Floods

Let's take a look at what the IPCC and recent research actually says

According to a poll conducted in late 2021, “Ninety-five percent of Americans believe the spread of misinformation is a problem.” As I have documented for more than a decade, public representations in the major media of the relationship of climate change and disasters is chock full of misinformation. What makes this issue fairly unique is the role played by journalists and some scientists in helping to spread that misinformation, while ignoring peer-reviewed science and consensus assessments.

In Part 4 of this ongoing series titled “What the media won’t tell you about . . “ I focus on climate change and floods. Earlier posts in this series focused on:

Today’s post is organized into three sections: (1) What the most recent reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and U.S. National Climate Assessment (NCA) say about floods, (2) trends in the societal impacts of flooding, specifically damage, deaths and people affected, and (3) what the most recent literature says about flooding and its impacts into the future.

What the IPCC and U.S. NCA say about flooding

The IPCC is unequivocal in its conclusions about the relationship of floods and climate change (for a quick primer on detection and attribution as used by the IPCC, have a quick look here):

In summary there is low confidence in the human influence on the changes in high river flows on the global scale. In general, there is low confidence in attributing changes in the probability or magnitude of flood events to human influence because of a limited number of studies, differences in the results of these studies and large modelling uncertainties.

That means that the IPCC does not have confidence in overall trends in flooding. It also means that the IPCC similarly does not have confidence that the “probability or magnitude of flood events” can be attributed to climate change.

The IPCC could not be more clear.

Let’s contrast what the IPCC says with a few recent media reports:

NPR: “How climate change drives inland floods” (shown also at the top of this post)

The Washington Post: “both drought and flooding are closely tied to human-driven warming”

New York Times: “When it comes to river floods, climate change is likely exacerbating the frequency and intensity of the extreme flood events”

The three articles have in common a common feature: each ignored the consensus conclusions of the most recent IPCC report. The New York Times article is particularly egregious in that the cited passage alleging increasing floods does not actually refer to historical observations, but instead to a study projecting future flooding under the infamous RCP8.5 scenario. Don’t get me started.

The IPCC — which deserves a lot of kudos for this — explicitly warned against associating increases in extreme rainfall (even if attributed to human causes) with flooding caused by climate change:

Attributing changes in heavy precipitation to anthropogenic activities (Section 11.4.4) cannot be readily translated to attributing changes in floods to human activities, because precipitation is only one of the multiple factors, albeit an important one, that affect floods.

The lack of direct relationship between extreme precipitation and flooding is something that we were among the first to document empirically more than 20 years ago.

And there is more that may be surprising — In the United States, according to the U.S. NCA, it is not even appropriate to attribute an increase in extreme precipitation to climate change (emphasis added in the below).

The complex mix of processes complicates the formal attribution of observed flooding trends to anthropogenic climate change and suggests that additional scientific rigor is needed in flood attribution studies. As noted above, precipitation increases have been found to strongly influence changes in flood statistics. However, in U.S. regions, no formal attribution of precipitation changes to anthropogenic forcing has been made so far, so indirect attribution of flooding changes is not possible. Hence, no formal attribution of observed flooding changes to anthropogenic forcing has been claimed.

The casual attribution of heavy rains to climate change and then by extension any associated flooding to climate change is like catnip for the media (see here and here). However, such claims are not supported by consensus scientific assessments.

The bottom line from these recent consensus assessments is clear:

Flooding has variously increased and decreased over different time periods in different places around the world (including the U.S.), but no overall trend has been detected.

In the absence of an overall increase (or decrease) there is no trend to be explained, hence attribution of flooding to climate change has not be achieved.

Finally, despite evidence for increases (in some places) in extreme precipitation attributable to climate change, the IPCC is explicit that this cannot be extended to flooding. And in the U.S., the NCA is explicit that attribution to climate change of detected increases in extreme precipitation in some regions is “not possible.”

Flood impacts

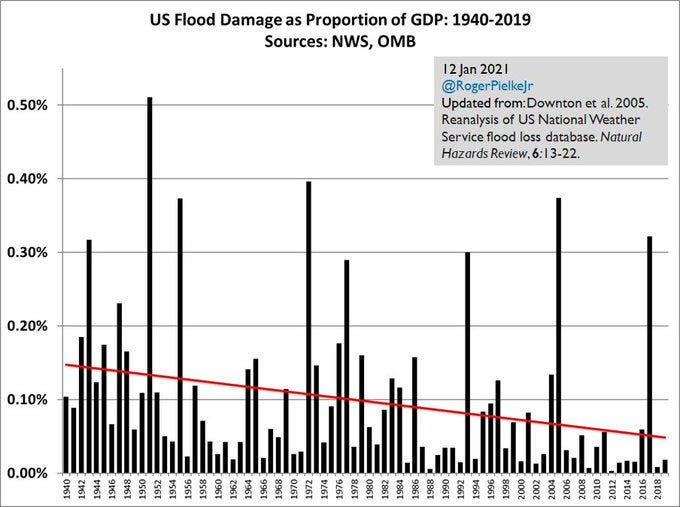

The graph above shows the economic impact of flooding in the United States from 1940 to 2019, updated from a 2005 paper of ours. The figure shows that flood damage in the U.S. dropped as a proportion of GDP by about 70% over 8 decades. That is incredible, and it should be welcome good news. The U.S. is doing much better when it comes to flood impacts that it did during my grandparents’ era.

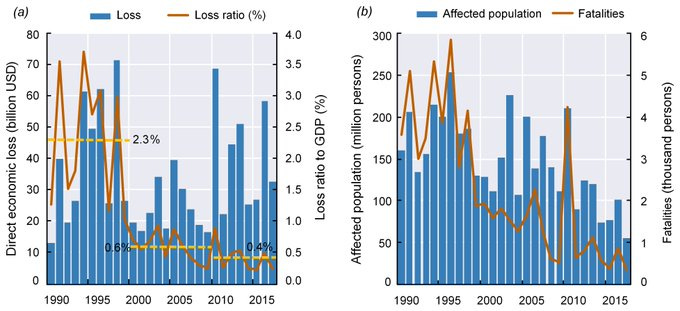

The good news on flooding is not just in the U.S.. The figure above from Du et al. 2019 shows for floods in China an even greater decrease in economic losses (as a proportion of GDP, “loss ratio”), as well as sharp decreases in affected population and fatalities.

These trends are also global, with a decrease “from around 150m people affected/yr to 40m people & from ~10,000 fatalities/yr to 4,000.” That’s about a 75% decrease in people affected and a 60% decrease in fatalities.

Yet another study concluded:

[L]ong-term trends in flood vulnerability between 1960 and 2013 were analysed. In accordance with a previous study, global mortality rates and global loss rates showed a decreasing trend (Fig. 2), and inverse relationships were found between flood vulnerability and GDP per capita (Fig. 3), indicating an improvement in flood vulnerability at the global scale since 1960 associated with economic growth.

There can be little doubt that overall around the world flood impacts to people and the economy are sharply down in recent decades (while acknowledging that some regions have seen more or less progress). Of course, it is not just floods, but across a wide range of weather and climate phenomena the world has seen a long-term decrease in associated vulnerability.

This is great news, and probably news most people have never heard.

Flood futures

The IPCC is fairly equivocal in its projections of future changes in flooding:

At the continental and regional scales, the projected changes in floods are uneven in different parts of the world, but there is a larger fraction of regions with an increase than with a decrease over the 21st century . . . these results suggest medium confidence in flood trends at the global scale, but low confidence in projected regional changes.

At the regional level the IPCC projects:

Increases in flood frequency or magnitude are identified for south-eastern and northern Asia and India (high agreement across studies), eastern and tropical Africa, and the high latitudes of North America (medium agreement), while decreasing frequency or magnitude is found for central and eastern Europe and the Mediterranean (high confidence), and parts of South America, southern and central North America, and south-west Africa (low confidence).

Careful readers will note that one of the areas where flooding is projected to decrease in frequency or magnitude in “southern and central North America” which is where floods have occurred in recent weeks, and have been confidently attributed to climate change across the major media.

Whatever climate change does or does not do to future patterns of flooding, there is good news here as well. The overall trend of decreasing vulnerability to floods that lies behind the massive decrease in societal impacts documented above is expected to continue — so long as we keep paying attention to flood mitigation and adaptation. Decreasing vulnerability does not happen by magic, it requires conscious action and smart decisions.

One new pre-print has looked careful at flood adaptation and reports good news:

Using a global panel of cities, this paper provides evidence of flood adaptation taking place. Cities are becoming more resilient with time. Repeated experience with floods does tend to re-duce the marginal economic impact of subsequent floods, while flood protection infrastructure, specifically dams, also helps mitigate a significant portion of the negative impact.

Increased resilience against flooding can continue into the future, offsetting the effects of projected climate change even under extreme scenarios, according to multiple modeling studies. This is good news because it means that uncertainty about the climate future need not stand in the way of actions to reduce vulnerability to floods. We know well how to do that.

Paying subscribers to The Honest Broker receive subscriber-only posts, regular pointers to recommended readings, occasional direct emails with PDFs of my books and paywalled writings and the opportunity to participate in conversations on the site. I am also looking for additional ways to add value to those who see fit to support my work.

There are three subscription models:

1. The annual subscription: $80 annually

2. The standard monthly subscription: $8 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

3. Founders club: $500 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who have the ability or interest to support my work at a higher level.

When you cite the IPCC reports are you distinguishing between the Science/Technical reports and the Summary for Policy Makers?

This has been an excellent series.

Clearly we need to be spending more on adaptability than wasting it on mitigation.