What Jonathan Haidt Gets Wrong About Universities

Like it or not, truth and politics go hand-in-hand

Jonathan Haidt, a professor of psychology at New York University and founder of the Heterodox Academy (of which I am proudly a member), recently announced that he would resign from his primary professional association, the Society for Personality and Social Psychology (SPSP). Haidt explained that his resignation from the SPSP was due to its adoption of new guidelines for presentations proposed for its annual meeting asking “people to indicate how their presentation advances the Equity and Anti-racism goals of SPSP.”

Haidt explains what happened (and Lee Jussim provides a more detailed tick-tock with the backstory of Haidt’s resignation):

I was going to attend the annual conference in Atlanta next February to present some research with colleagues on a new and improved version of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire. I was surprised to learn about a new rule: In order to present research at the conference, all social psychologists are now required to submit a statement explaining “whether and how this submission advances the equity, inclusion, and anti-racism goals of SPSP.” Our research proposal would be evaluated on older criteria of scientific merit, along with this new criterion.

Haidt argues that the elevation of social justice as a criteria for evaluating SPSP proposals compromises the ability of members of the organization to pursue “the truth.”

This is a version of Haidt’s view of the ultimate purpose of a university:

[U]niversities can have many goals (such as fiscal health and successful sports teams) and many values (such as social justice, national service, or Christian humility), but they can have only one telos, because a telos is like a North Star. An institution can rotate on one axis only. If it tries to elevate a second goal or value to the status of a telos, it is like trying to get a spinning top or rotating solar system to simultaneously rotate around two axes. I argued that the protests and changes that were suddenly sweeping through universities were attempts to elevate the value of social justice to become a second telos, which would require a huge restructuring of universities and their norms in ways that damaged their ability to find truth.

Haidt’s grasp of celestial mechanics aside, I find his arguments unconvincing for three reasons: First, the SPSP is a club and can make its rules however it wants; Second, Haidt relies on the mythology of the modern university, not its reality; and Third, “the” truth does not exist separate from politics.

Let’s take these each in turn.

Academic Clubs

Let’s face it, professional associations are like country clubs. You pay a fee to join. They host events and socials. They enable networking and professional opportunities. They are self-governing and in varying degrees put forward values and goals for the association based on a subset of members in leadership roles. They give awards and mete out status, some have scientific journals and annual meetings.

The SPSP, like most academic associations, has long been overtly political. It currently advertises that the organization advocates for policy in five areas, which you can see below in a screen shot from their web site.

Like most organized groups, the SPSP is comprised of people who share values and come together to try to advance those values. Political advocacy offers one way forward. It is no surprise that addressing racism has been adopted as a criterion for evaluating presentations given at its annual meeting because the topic is a SPSP institutional priority area.

Haidt writes, “I am especially dubious of the wisdom of making an academic organization more overtly political in its mission.” It appears that Haidt’s complaint is not simply that the SPSP is overtly political — It’s that the particular politics of the SPSP today and how it is pursuing them do not appear to be those shared by Haidt.

Haidt would appear to get this when he explains:

[W[hen members of an organization perceive that the quality of an organization, or its value to them, has declined. They then have three alternatives: They can exit the organization, they can voice their objections within the organization, or they can stay loyal to the organization as it currently is by doing nothing, or by attacking those who criticize it.

For Haidt, the conclusion is that “soon it will be time for exit.”

What’s a University for Anyway?

Haidt believes that a university’s highest calling, its primary goal, is the pursuit of the truth. You can see Haidt making this case in the Hayek lecture above given at Duke University in 2016. Heterodox Academy, true to its name, has hosted multiple perspectives challenging Haidt’s axiology, such as by John Tomasi arguing the curiosity not truth defines universities, and Oliver Traldi arguing that it is knowledge, understanding, and explanation rather than truth.

The purpose of the modern university is worth a longer discussion which would take us to some uncomfortable places involving concepts like profit, power and college football. That larger discussion will have to wait for another time. I have been a creature of the modern university for pretty much my whole life and I do not recognize the modern university to be uniquely distinguished by a shared commitment to the truth.

For instance, have a look below at the Mission, Vision and Values of the University of Colorado Boulder, where I have been on the faculty since 2001. One word you don’t see anywhere? Truth. You don’t even see science or research.

Despite the fact that “truth” does not appear in my university’s mission I feel no pressure against pursuing truth in my research and in my teaching. Similarly, my home department has adopted a commitment to “anti-racism” using exactly the same vocabulary that Haidt has objected so strongly to: “we commit to building an inclusive and anti-racist Environmental Studies program. We will educate ourselves to become active anti-racists in our program and on campus. We will analyze and change our policies to ensure we are not perpetuating racism . . .”.

Unlike Haidt, I welcome such language. Not for what it implies for me — I’m a faculty member with academic freedom, which is sacrosanct — but what it implies for the leadership of my university. Consider that my department enrolled 649 freshmen in the past 5 years, and just 6 of them were black students. So much for not perpetuating racism. My university and my department have a racism problem as I have documented, so public statements from university leaders about their commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion are welcome because they underscore the vast chasm between words and reality.

I’ve heard concerns expressed by Haidt and others that commitments to social justice at universities (or professional associations as is the case here) will diminish the ability of early-career scholars to pursue truths as they see them. However, I’ve yet to meet any scholar on my campus or elsewhere who has indicated such outcomes arising from these commitments. Trust me, I know very well what it is like to have political pressure applied because someone rich or powerful did not like my research, and to actions seeking to redirect me from pursuing the truth. Expressed commitments to achieving social justice outcomes are not nearly the same thing.

No Such Thing as “The Truth”

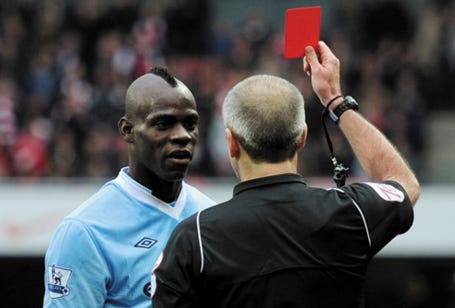

Do black soccer players get more red cards? Surely this is a question on which we can establish “the truth.” For reasons I explained in some detail last week, it turns out the truth of this matter is complicated. With an overlay of racism in professional football (soccer) the issues become far more complicated.

In his writings Haidt usually prefaces “truth” with “the” — a construction which comes far too close to reinforcing a fact-value dichotomy that we scholars of science in society have long been viewed as problematic.

Consider an issue that I have been studying — eligibility of transgender athletes in elite sport competition. You won’t be surprised (especially if you are a long-time reader here) to learn that some people view as TRUTH that one’s gender/sex identified at birth is immutable, whereas other believe as TRUTH that one can change gender/sex categories. Both views are sincerely held. Both have profound legal and political implications.

The pursuit of “truth” in the modern university related to issues of great societal importance will always be messy, contested, value-laden and, yes, political. There is no way around it. That means that our pursuit of truth must be compatible with larger objectives. Curing disease, limiting environmental degradation and realizing social justice in academia and beyond are among these larger objectives. Imagine a disease researcher objecting to a request that they identify how their research contributes to addressing public health as a distraction from pursuing “the truth.” That would seem silly in that context, right?

I have no problem with Jonathan Haidt deciding to leave his professional association. I am empathetic that it must be difficult after so many years being in that particular “club.” At the same time I do not see his departure as anything more significant than a prominent member of an organization leaving because he sees that its common values have departed from his own. Most of us have joined or left organizations for the same reason, it’s just not big news.

If efforts were taken to restrict or punish Haidt’s (or any other academic’s) right to freedom of expression, I’d have a different view. Social and political pressures to conform are of course real and each of us has to decide how we will deal with these when we engage in expression that others may find unwelcome. Any highly visible academic or public intellectual will at some point experience push back if their work has impact, so prepare for it if your goal is engage in issues of our day.

Make no mistake, racism is one of those issues. Talking about it, elevating its significance in the academy and putting in place incentives to do more are not threats to our research or pursuit of truth.

I’m glad I retired before the anti racism police arrived at the company I worked at for 35 years. I view this latest iteration of requirements placed on presenters that Haidt speaks of as simply a tax. Something that causes people in the workplace to be diverted from their primary focus (manufacturing something, serving a client, etc...) - that causes them to have to spend more time doing their job. And that’s a problem. Having invested a lifetime of 70 hours weeks serving my clients demands, adding other requirements that do not get embedded into the deliverable or advice given to the client serves no purpose in my opinion. If you cut the legs out of a true meritocracy, eventually it will no longer be best in class.

I do respect your point of view and appreciate your position.

I just know that in my prior work-life, adding more requirements would have been fatal, there just were not enough hours in the day and additional requirements would have put pressure on quality. And that’s very dangerous.

At the same time, the “culture” of any organization can achieve anti racist objectives without building in requirements similar to what Haidt speaks of. It comes from developing appropriate processes into recruiting, engaging in the community, engaging with your suppliers and customers, training and coaching your people and many other aspects of an organization. Culture is set at the top, but if done properly, is an extremely powerful force that resonates from the bottom up - when all of the ores are in the water pushing in the same direction. I was lucky to work with subject matter experts at the top of their field from a very diverse (color, nationality, religion, gender, etc.....) back ground. The one thing they all had in common was getting the best result for - - the client.

Nevertheless, Haidt has the right to leave this SPSP for any reason.

As you write, he may be wrong about the purpose of a university (truth instead of curiosity).

But, asking "people to indicate how their presentation advances the Equity and Anti-racism goals of SPSP" means that all association's activities should include "affirmative action" to advance equity and/or anti-racism. Should it do so? Why this in particular?

Regardless of the value of such moral goals, it is doubtful that Personality and Social Psychology has nothing else to discuss regarding their profession.

For example, what should be the content of the political correctness statement of the authors of the study on "Mechanisms linking attachment orientation to sleep quality in married couples" that has just been published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin (PSPB)? Should they make up something to tell and then expose themselves to the possible accusation of being insincere?

This self-righteousness smells of Soviet-style inquisitiveness with an awfully bad taste.

So, Haidt may have a good reason to leave this professional association.