Why is the University of Colorado Boulder so White?

Part 1: Enrollment management and campus budgets hooked on out-of-state tuition are not the whole story, but they are a big part of it

I’ve been on the faculty at CU Boulder since 2001. Soon after arriving I started wondering about a troubling pattern in my classes. I had almost no Black students in them. Despite various initiatives, lofty goals and frequent statements of the importance of diversity from administrators, that remains the case today. CU Boulder is one of the least diverse and most inaccessible campuses among universities in the nation. That’s a problem.

This is the first in a series of posts on diversity in higher education and at CU Boulder in particular. Uncomfortable as it may be, change starts at home. Diversity has many facets on a university campus – faculty, staff, graduate students, undergraduate students, athletics, programs etc., as well as different elements typically considered under the umbrella of diversity, such as race, ethnicity, gender, age, economics, politics, etc. Today, I look at the population of Black students as undergraduates at my institution.

To start, let’s look at some numbers from my campus – which are troubling and embarrassing. To the credit of CU Boulder, these data are readily and publicly available.

Consider these facts. Over the past 5 years the program that I belong to, Environmental Studies, has enrolled 622 entering freshmen. Of those 2 (two) have identified as “African American” (my campus uses various terminology to describe its demographics, in what follows I use what the cited source uses when describing their data). Since Environmental Studies was established in 1994, only 20 African American students entered our program as freshmen, out of 2,526 (<1%) total students. No wonder I have had so few Black students in my courses.

The lack of diversity in our Environmental Studies Program is by no means unique across the various departments on campus. Currently in fall 2021, CU Boulder has an undergraduate enrollment of 29,511 students, of which 802 or about 2.7% are Black/African American. In 2016 it was ~2.5%. There is no way to sugarcoat these data. A long-stated goal of campus leaders has been to increase the diversity of its student population. Progress has been, generously, slow.

This is no revelation. In a 2020 report the Education Trust gave the University of Colorado Boulder an “F” for Black student access. That report estimated that in Colorado (in 2017) about 4.9% of 18 to 24-year-olds were Black, a figure much higher than CU Boulder enrollment. Consider also that The University of Colorado Boulder has a large proportion of out-of-state students, and 13.4% of Americans are Black or African American. CU Boulder is overwhelmingly inaccessible to Black students, that is just a fact.

The lack of accessibility to top public universities is a national problem. The Education Trust concludes of trends in accessibility across top public universities: “Our findings show very little progress has been made since 2000, and the overwhelming majority of the nation’s most selective public colleges are still inaccessible for Black and Latino undergraduates. Over half of the 101 institutions earned D’s and F’s for access for BOTH Black and Latino students” (emphsais in original).

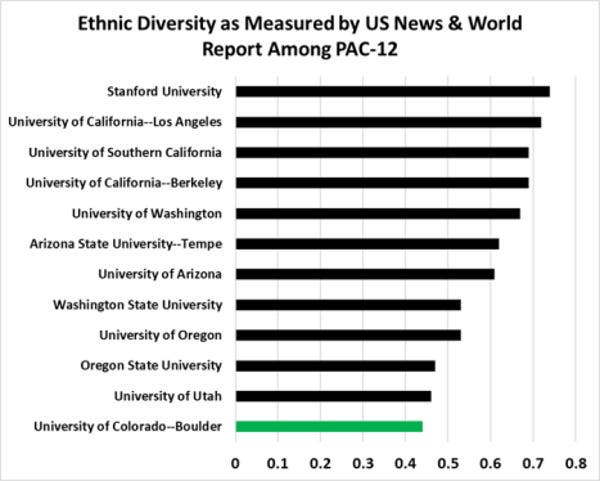

Even so, CU Boulder is particularly inaccessible among its peer institutions. According to the U.S. News and World Report college rankings, in the PAC-12 conference the University of Colorado Boulder ranks as the least diverse university in the conference.

For the past several years, I have invested a lot of time trying to understand the lack of diversity on my campus and why, despite the frequent lofty words from administrators, little seems to be changing. The short answer is that it is complicated. But so too are a lot of important challenges -- complexity is no excuse for policy failure.

Last spring, I taught a graduate seminar focused on diversity at CU Boulder as a policy problem, and what follows is informed by our collected work (I had some awesome students). However, the views expressed in this and subsequent posts are mine alone.

If there is one factor that stands out as responsible for the continuing lack of diversity at CU Boulder it is M-O-N-E-Y. In short, the campus needs money to run — a lot of money — and so it has chosen to draw disproportionately from wealthy families to populate its undergraduate cohorts. This is especially so with out-of-state students whose families can pay the high out-of-state tuition.

The reliance of CU Boulder on wealthy students is remarkable -- A 2020 analysis found that 8.2% of University of Colorado undergrads came from families in the top 1% of national income and 41.4% came from the top 10%. An important detail: The analysis did not break out CU Boulder from the other three campuses of the University of Colorado System (Colorado Springs, Denver, Anschutz medial school) so the proportion of students in the top 1% of income on the Boulder campus alone was certainly higher than 8.2%. But even so, these data were enough for the University of Colorado overall to rank 1st nationally among public universities for its proportion of undergraduate students from the top 1%.

Why the University of Colorado Boulder relies so much on wealthy students is a long and fascinating story (to be the subject of a future post), and can be traced back to tax policies in the state going back to the 1980s. In many states public investments in higher education have diminished in recent decades, creating incentives for universities to rely increasingly on out-of-state tuition to fill that gap. Colorado has not bee unique.

However, the state of Colorado has been among the most aggressive in defunding higher education in recent decades, amplifying these incentives. Consider that in Colorado in the early 2000s state funds made up about 2/3 of higher education budgets with tuition making up about 1/3. Today, that ratio has been reversed. The Colorado State Legislature explains: “The state’s most selective institutions rely heavily on nonresident tuition to subsidize their operations.” Without wealthy students from out-of-state, many public universities would face a deep financial crisis, and CU Boulder especially so.

In the United States the demographics of the wealthy are skewed toward white families, as shown in the graph below, which shows income distributions for white and black households. So if universities emphasize recruitment from the wealthy, they will build in a disproportionate bias towards white students. Consider that in 2020 the top 1% of households earned more than $360,000. This shows that racist outcomes do not require racist intent.

The focus on the wealthy is exactly what university administrators have done intentionally in recent decades. The overwhelming need for M-O-N-E-Y in public universities has led to the creation of an entirely new industry called “enrollment management.” Stephen Burd of New America explains that this new industry is characterized by high-priced consultants applying sophisticated quantitative tools to help universities recruit the “right” students:

Over the last several decades, an extremely lucrative industry has emerged that has transformed admissions and financial aid practices at both public and private four-year colleges and universities to the detriment of low-income students and students of color alike. Under the sway of the enrollment management industry—private consultants who develop strategies for student recruiting—many colleges are engaged in an arms race for the students they most desire: the “best and brightest” and the wealthiest. As a result of this fevered competition, colleges are devoting fewer institutional aid dollars than they otherwise could and making fewer seats available to students from less privileged backgrounds.

In The Merit Myth: How Colleges Favor the Rich and Divide America, Anthony Carnevale, Peter Schmidt and Jeff Strohl argue that enrollment management is a black box that strongly influences who has access to college campuses:

[E]nrollment management allows colleges to mask a deliberate choice made in pursuing their institutional interests. College officials who would never admit outright to wanting to reduce numbers of low-income students can use enrollment management to twist the knobs to produce such a result. Enrollment management can cause suspicion because it’s carried out through complex mathematical analyses and often produces results best explained in cynical terms, yet the mischief stems not from the tools used, but from the ends pursued. . . Many in the admissions offices sincerely care about students from less-advantaged backgrounds. But they’re stuck working within a system that’s defined by its own biases: that applies admissions criteria to meet shifting institutional criteria to meet shifting institutional priorities rather than to enforce rigid standards of merit; that has few, if any, firewalls to maintain its integrity and prevent inappropriate interference; and that allows market pressures and bottom-line concerns to overrule good deeds.

At many public universities, an over-riding institutional priority over the past decade has been not only to balance the books, but to grow and growth requires evermore money. But then COVID-19 revealed the fragility of many campus budget models. Forget growth, now treading water is seen as success. Consider that on my campus a decline of out-of-state enrollment by 1% translates into a ~$5m hit to the campus operating budget (estimated at about $730m in 2020-21) and out-of-state tuition comprises almost 2/3 of the campus’ operating budget. Non-resident tuition declined by about $60m during the pandemic.

Public universities are dependent upon out-of-state tuition to such a degree that seeing it diminish permanently would lead to a budget crisis requiring significant actions to cut spending. It is unclear whether enrollment management algorithms and implementation played any role, but in 2021 CU Boulder saw its enrollment of freshmen Black students drop for the first time since 2006, even as overall enrollment rebounded to nearly 2019 levels. What happens inside the enrollment management black box apparently stays in the black box.

When I have given talks on this subject on my campus in different departments I am often asked, “What can we faculty do to diversify our undergraduate population?” – and the answer is almost nothing. Admissions and enrollment are functions that occur far removed from the faculty and takes place via mechanisms mostly hidden from view.

Of course, enrollment management is not the whole story to the lack of accessibility to public universities. As I said, it is complicated. But make no mistake, enrollment management is an important part of understanding why universities fall short in achieving their goals for diversity. An important step would be for administrators to open up the black box of enrollment management, to make public its role in undergraduate accessibility (and lack thereof) and to create processes with greater oversight by faculty and students alike. We can manage enrollment differently than we have, of that I am sure.

Subsequent posts will look at athletics, faculty, staff, graduate students and the different dimensions of the challenge of succeeding with respect to the goals often advanced by university administrators but for which we fall short. We must do better.

How about admitting students based on their academic achievements and not on skin color? Don't give a certain percentage admission just because they are black. That is racism. How degrading to those blacks that make the grade. Admissions should be color blind.

You confuse racism with geographic, cultural, and other differences between groups. Your university has no moral nor ethical obligation to achieve a given target for any specific group, and you are actually being racist by singling out African Americans (I assume you're trying to get brownie points within a woke University bubble, or it makes you feel good to conform to the left's emergent racist culture, which emphasizes a muddled idea of "race" into everything they say or do). Think about it, it seems that, according to the ideology you display, your university should also have the appropiate proportion of Jews, Muslims, Vietnamese, Cubans, and other groups? Do you realize how divisive and RACIST is that proposition?