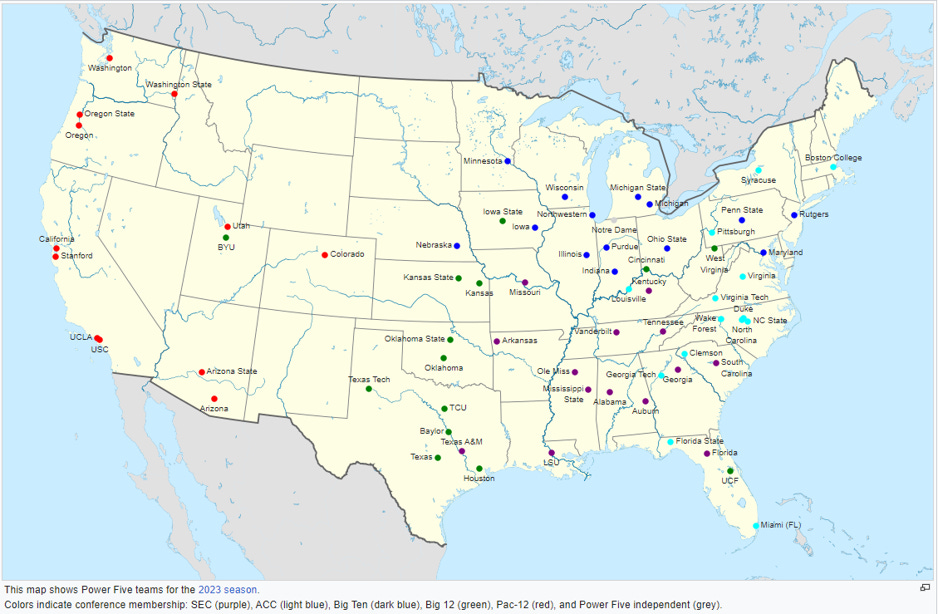

According to the U.S. government, the more than 3,700 colleges and universities across the United States in 2021 enrolled more than 18.6 million students. A tiny fraction of these institutions also oversee professional football teams. In recent days there has been upheaval in how these 69 universities organize their football programs into conferences. These five conferences (soon to be four) comprise what is called the “Power 5” division.

The University of Colorado Boulder — where I am a professor — has been at the very center of the upheaval, having announced last week that it was leaving the Pac-12 conference for the Big 12, one of the other Power 5 conferences — and the future of the Pac-12 is now uncertain after 8 schools have now departed.

Today I share some thoughts on what the recent college football realignment tells us about elite public and private universities in the United States. The main takeaway of the football drama of the past week is to openly acknowledge that elite, mostly public, universities have three primary functions.

These functions are:

Providing in exchange for tuition and fees an amenity-rich experience for students that includes an opportunity for an education, and culminates with a credential;

Conducting world-class research, and in some cases research-related services such as in hospitals run by many universities;

Hosting a professional football program, which offers another amenity to the students, but which also stands on its own as a core university function. Universities sponsor other sports, but nothing remotely compares to the importance of football.

Let’s take a closer look at each.

Universities as Amenity-Based Experiences for the Wealthy

Writing at Persuasion recently, William Deresiewicz explained that most college students have experiences that are very different than those who attend schools like Harvard or Stanford. In fact, his argument holds more broadly for students that attend the Power 5 schools that host big-time football programs:

Of the nation’s 16 million undergraduates, 78% go to public institutions, 30% go to community colleges, 38% go part-time, and 38% are 22 or older. The vast majority of four-year schools take most of the people who apply to them; a quarter are open enrollment, which means they take everyone. If most of your friends went to selective colleges, congratulations, you’re in the elite. You need to get out more.

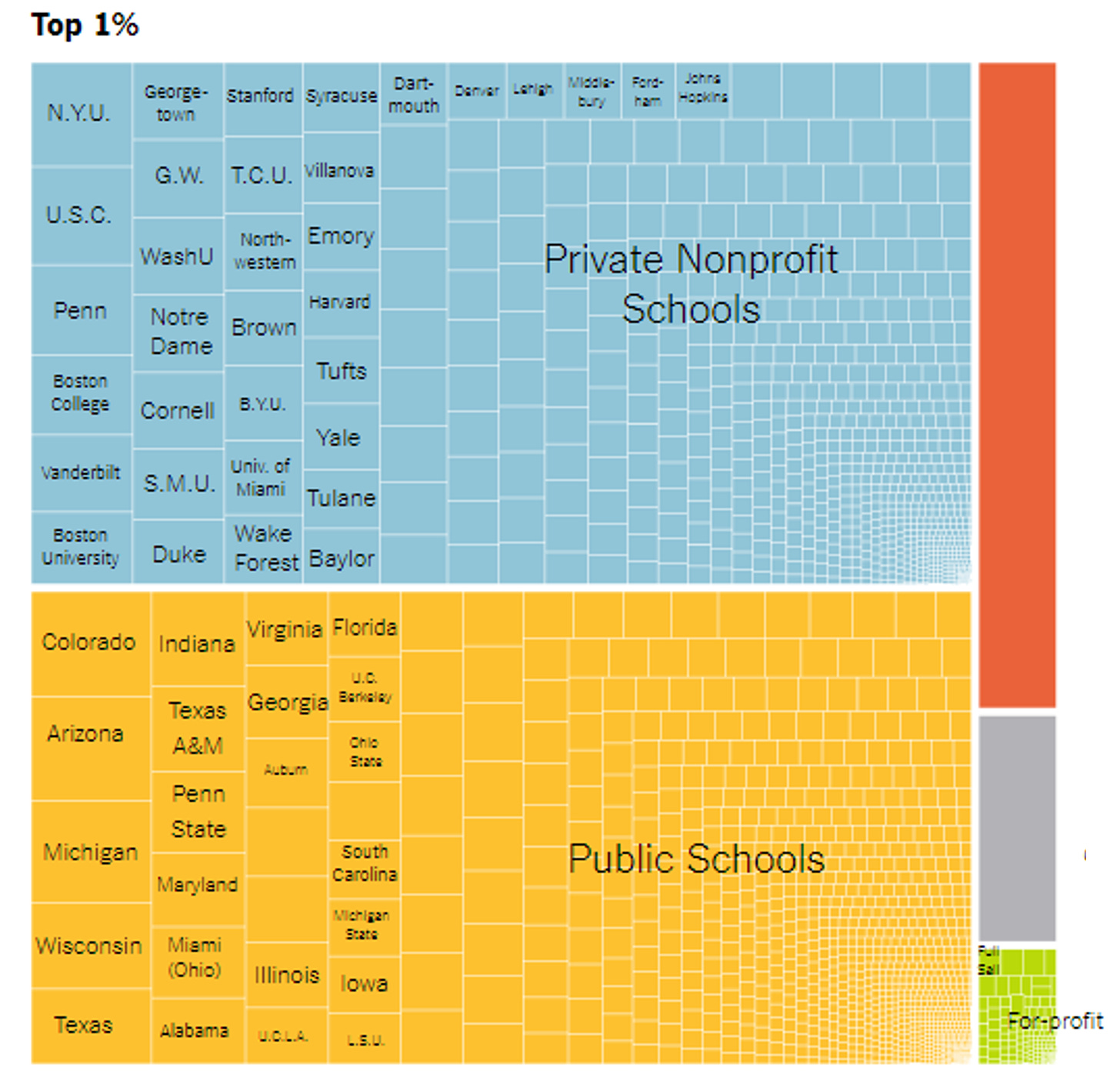

The figure below, from a New York Times analysis of data published by Raj Chetty and colleagues in 2017 shows that students from families with earnings that place them in the top 1% were disproportionately represented in state public universities.

Of the 23 public universities listed in the figure above, 22 are also members of the Power 5 football division. Leading the way in over-representation of the top 1% is the University of Colorado, which had 7.7% of its student body from the top 1%, and 59% from the top 20%. The median family income for all undergraduates was $133,700. Elsewhere, I’ve argued that this enrollment make-up is deeply problematic.

There are exceptions to these overall patterns. For instance, the University of California-Los Angeles (UCLA) was identified in the study as the university with the highest percentage of low- and middle-income students, with 19.2%.

There are complex reasons behind why public universities have become the locus of post-secondary education for the very wealthy and the merely well-to-do. Reasons include diminishing public support and increasing costs of attending these universities as they expand administration and offer various upscale amenities for their students. One of these amenities is a professional-like football team on campus. But there are many others, as college campuses have long sought to attract students with more than just educational opportunities.

Writing at Forbes almost a decade ago Cara Newlon described the college landscape as being about much more than education:

A free movie theater. A 25 person hot tub and spa with a lazy river and whirlpool. A leisure pool with biometric hand scanners for secure entry. A 50 foot climbing wall to make exercise interesting. And a top-of-the-line steak restaurant with free five course meals.

This isn’t a list of items from a resort brochure. They’re facilities you can find on a college campus. And with college construction costs rising, it could be the best four-year getaway you've ever had.

The Power 5 universities have a significant problem with being accessible to large numbers of people across the country — disproportionately black, Hispanic and lower income. These universities also have also seen large declines in public confidence. Serving primarily the elite has consequences.

Universities as Research Powerhouses

Of the top 55 universities in terms of funding for research and development in 2021, according to the National Science Foundation, 37 of them are in the Power 5 football division (most of the 18 other universities in the top 55 do not have NCAA Division 1 football). These 37 schools collectively spent more than $34 billion on research and development in 2021, or about one third of all non-defense federal expenditures for R&D.

My campus reported more than $650 million in R&D funding in 2022. For comparison, in 2022 the University of Colorado Boulder received almost $900 million in tuition. The total campus budget exceeds $2 billion.

The co-location of undergraduate education and world-class research has a long history, and has its tensions along with many benefits. Some universities also run hospitals in conjunction with their medical schools — in Colorado the university hospital is not on my campus but is part of the University of Colorado system.

Much more could be said about universities and R&D, but for today, know that most Power 5 schools have more than $500 million, and many over $1 billion, sponsored research that is a core function of the institutions that is every bit as important (and often tightly connected) as its broader educational objectives.

Universities as Hosts of Professional Football Teams

Let’s just tell it like it is — Running a professional football team is a core function of the Power 5 university, and has been for many decades. College football is not extra-curricular nor are the players “amateurs.” The dash-for-cash that we have observed over the past week as the Pac-12 has fallen apart clearly shows that “money matters more than shiny trophies.”

Let’s look at some numbers.

The 54 public Power 5 universities reported athletic department budgets of about $7.5 billion for 2021-22, according to USA Today. Add in the private schools which do not report their budgets and the entire Power 5 budget for sports is likely closer to about $9 billion. That is similar to the NFL, which had a reported $11.9 billion in revenue 2022. Not all of college athletics budgetary expenditures go to football, but most of the revenues come from football.

At the University of Colorado Boulder, according to a report just released by the state government, in 2022 the football program brought in about $23 million more than its total expenses — that’s about $230,000 per participating football player. That money was used to pay coaches, administrators and to subsidize the other sports that the University sponsors, a requirement of the NCAA and its conference.

Again, let’s just tell it like it is — Colorado is of course not unique, but typical — the labor of mostly black athletes generates income that the universities use to support the tuition, fees, sports participation (and more) of the other college athletes, who are mostly white. The university subsidizes the athletics department with another $12 million per year and the head coach is on a $29.5 million contract. The finances of big-time college football are not ethical or appropriate, and are one reason why college sports are on a fast-track to true professionalization — including recognition for athlete rights, market-based employment and compensation.

The numbers also tell us how different the Power 5 universities are from their little siblings, the 65 members “Group of 5” universities. These universities also have aspirations of hosting big-time football programs, and in some respects they do — in 2022 the 54 public members collectively had a budget for athletics of more than $2.2 billion.

However, 60% of this budget, almost $1.3 billion, was the result of universities subsidizing these programs at a median rate of more than $23 million per school. These funds typically are siphoned from student tuition that would otherwise support other university functions. In contrast, the Power 5 schools overall saw only about a $5 million median subsidy per university, representing about 4% of the Power 5 division’s collective budget.

Anyway you look at it, college football is central to the mission of Power 5 universities, and every bit as important as education and research. Universities should acknowledge this reality and govern appropriately.

Understanding The Power 5

The Power 5 universities are in a class by themselves. They have three primary functions:

Providing tuition-paying students an experience, education, and credentials

Performing world class research

Hosting a professional football team

Everything else is secondary.

If it seems strange that these three institutional priorities are together a weird mash-up, well, welcome to America. Football is deeply ingrained in American culture and so it is no surprise that the sport has found a permanent home in U.S. universities. It may be the one university function that enjoys broad support across the country among those who have attended college and who have not.

I am a creature of the U.S. Power 5 university, having spent decades at Colorado. Education, research and football are all deeply valued — I value them too — but each has significant issues these days, both on their own and where they meet.

The conference realignment saga of the past week highlights that universities need to improve their governance. We can do much better in serving the communities of which we are a part while while maintaining traditions and culture. I’ll have some specific proposals for reforming these unique universities in columns to come. There is a lot to do.

Read more:

My pre-pandemic 2019 paper: After Peak Football: Trends in and Futures for America’s Most Popular Sport

My 2023 update

My series on the future of football

Thanks for reading! I value your comments and discussion. Please like and share this post. Please consider a subscription at any level. And if you already a subscriber, thanks! You make THB possible.

This is a subject I have mixed feelings about. I am from Iowa, and went to the University of Iowa in 2005. Because state of Iowa has no professional sports at all, and with football being as popular as it is... well, there's a reason Iowa fans are among the most loyal and boisterous in the nation, the population of Iowa City grows about 55,000 on game day- the die hard Hawkeye fan base is known to travel in large numbers to bowl games. The day Iowa fans show up en masse for a game, the city's beer supply is sure to decrease sharply. Iowa football always seems to be just good enough to rank, sometimes hitting the top 10, but they're typically a few specialty positions short of national championships. Also the slow, grinding game plan of Kirk Ferentz, the longest tenured head coach in the nation, since 1998. Iowa has produced a remarkable amount of NFL linemen, tight ends, and secondary players for a school that doesn't aquire many 5 star recruits. I digress, as you can tell, football is very important many an Iowan, and both Iowa and Iowa State are among the top research and AG schools in rhe nation.

The U of Iowa makes for a great example of how intertwined the universities are with their football teams. The Iowa Stead Children's hospital was completely a few years back, and because the hospital and the stadium are across right next to each other, a heart-warming tradition has begun. The 12th floor of the childrens hospital overlooks the stadium, and the children being treated in the hospital can see the home games. After the first quarter of every home game, all 55,000 people in the stadium and the players turn around and wave to the kids on the 12th floor- My sister-in-law is does research in oncology-hematology at Stead- this is a unique example of how all the bullshit, the controversy, etc. of money and athletics among universities, disappears for a few fleeting moments, giving a sick child a tear-jerking glimmer of hope.

My rough calculation from a year ago, using media reported data, is that with Oregon and Washington the new Big Ten has already achieved the largest collection of TV ratings eyeball potential, student enrollment, and football revenue per program of any conference, and may now be danger close to attaining an insurmountable hold on these positions (i.e.: such a strong advantage that no reasonably likely realignment in the rest of the game would challenge it) if just a couple of additional pieces fell into place (Stanford, Cal, plus a disgruntled Florida State, perhaps a nervous Notre Dame, etc...)

Do you have a strong professional take on these numbers?