Weather Attribution Alchemy

A new THB series takes a close look at extreme weather event attribution, Part 1

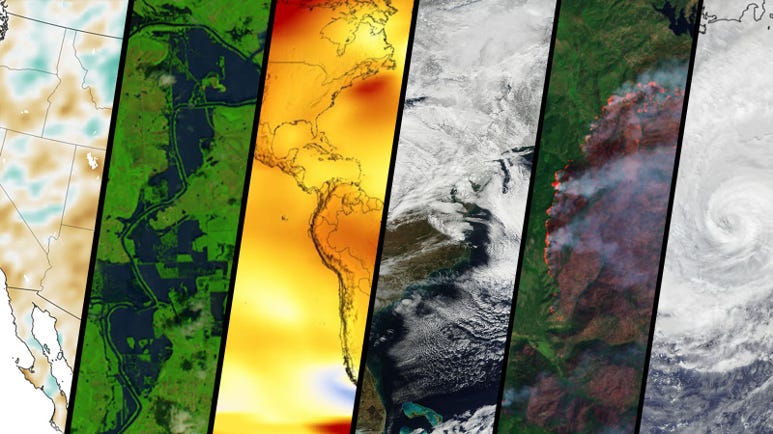

In the aftermath of many high profile extreme weather events we see headlines like the following:

Climate change made US and Mexico heatwave 35 times more likely — BBC

Study Finds Climate Change Doubled Likelihood of Recent European Floods — NYT

Severe Amazon Drought was Made 30 Times More Likely by Climate Change — Bloomberg

For those who closely follow climate science and the assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), such headlines can be difficult to make sense of because neither the IPCC nor the underlying scientific literature comes anywhere close to making such strong and certain claims of attribution.

How then might we understand such high profile claims?

I’ll try to answer this question in this new THB series — Weather Attribution Alchemy. Extreme weather event attribution has long been among the topics most requested by THB readers. In this first post in the series, I introduce some key concepts that will be important as the series evolves over the coming weeks and months. I’m counting on your engagement throughout the series.

Weather event attribution does not appear in the IPCC Glossary, however it does appear in the body of the AR6 report, where the IPCC explains that event attribution research seeks to “to attribute aspects of specific extreme weather and climate events to certain causes.”

The IPCC continues:

“Scientists cannot answer directly whether a particular event was caused by climate change,1 as extremes do occur naturally, and any specific weather and climate event is the result of a complex mix of human and natural factors. Instead, scientists quantify the relative importance of human and natural influences on the magnitude and/or probability of specific extreme weather events.”

In future installments we will get into the gory details — the strengths and weaknesses — of the various approaches to event attribution studies. With this post I want to introduce three starting points for our discussions which will unfold over a series of posts in coming weeks and months.

First, event attribution research is a form of tactical science — research performed explicitly to serve legal and political ends. This is not my opinion, but has been openly stated on many occasions by the researchers who developed and perform event attribution research.2 Such research is not always subjected to peer review, and this is often by design as peer-review takes much longer than the news cycle. Instead, event attribution studies are generally promoted via press release.

For instance, researchers behind the World Weather Attribution (WWA) initiative explain that one of their key motives in conducting such studies is, “increasing the ‘immediacy’ of climate change, thereby increasing support for mitigation.” WWA’s chief scientist, Friederike Otto, explains, “Unlike every other branch of climate science or science in general, event attribution was actually originally suggested with the courts in mind.” Another oft-quoted scientist who performs rapid attribution analyses, Michael Wehner, summarized their importance (emphasis in original) — “The most important message from this (and previous) analyses is that “Dangerous climate change is here now!”

Weather event attribution methodologies have been developed not just to feed media narratives or support general climate advocacy. Otto and others have been very forthright that the main function of such studies is to create a defensible scientific basis in support of lawsuits against fossil fuel companies — She explains the strategy in detail in this interview, From Extreme Event Attribution to Climate Litigation.

As I recently argued, tactical science is not necessarily bad science, but it should elevate the degree of scrutiny that such analyses face, especially when they generally are not subjected to independent peer review. In this series I’ll apply some scrutiny and invite you to participate as we go along.

Second, extreme event attribution was developed as a response to the failure of the IPCC’s conventional approach to detection and attribution (D&A) to reach high confidence in the detection of increasing trends in the frequency or intensity of most types of impactful extreme events — notably hurricanes, floods, drought, and tornadoes.

Here is how I recently explained the IPCC’s conventional approach to detection and attribution:

To ensure rigor in its work, the IPCC has employed a statistical framework for concluding that extreme weather phenomena has actually increased (or decreased) and the factors responsible for such changes. The detection of changes required quantifying a change in the statistics of weather extremes over climate time scales of 30 years or even longer. Once detection was achieved, then scientists seek to attribute those changes to particular causes, including the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

When it comes to many types of extreme events the IPCC has for decades been unable to conclusively detect changes in their frequency or intensity. For instance, the IPCC has reported increases in heat waves and in heavy precipitation, but not tropical cyclones (including hurricanes), floods, tornadoes or drought.

The IPCC’s inability to reach high confidence in detection and attribution of most types of extreme events has been viewed by climate advocates as politically problematic. For instance, Elizabeth Lloyd and Naomi Oreskes argue that the IPCC’s lack of strong claims on extreme event detection and attribution,

“. . . conveys the impression that we just do not know, which feeds into both contrarian claims that climate science is in a state of high uncertainty, doubt, or incompleteness, and the general tendency of humans to discount threats that are not imminent.”

The underlying theory of change here appears to be that people must be fearful of climate change and thus need come to understand that it threatens their lives, not in the future, but today and tomorrow. If they don’t have that fear, the argument goes, then they will discount the threat and fail to support the right climate policies. Hence, from this perspective, the IPCC”s failure to reach strong claims of detection and attribution represents a political problem — a problem that can be rectified via the invention of extreme event attribution.

The IPCC AR6 Working Group 1 acknowledges extreme event attribution research in its Chapter 11 but does not privilege it over the IPCC’s conventional approach to detection and attribution. The IPCC AR6 Chapter 12 relies on the IPCC’s conventional approach to detection and attribution, and appears to dismiss event attribution studies with a single sentence,

“The usefulness or applicability of available extreme event attribution methods for assessing climate-related risks remains subject to debate.”

I expect that there is to come a significant collision between those researchers who support the conventional IPCC approach to detection and attribution and those of a more activist inclination who favor single event attribution. This expected conflict will be the subject of a future post in this series.

Third, and finally for today, I want to once again emphasize the reality and risks of changes in climate due to human activities — notably the burning of fossil fuels, but also land use change, particulate pollution, and other forcings. The importance of climate change as an issue does not mean that we can or should ignore scientific integrity. We live in a time when far too often calls for scientific integrity are criticized by political campaigners (including scientists) when certain scientific understandings do not align perfectly with this or that political agenda.

For example, some dismiss entirely the possibility of human-caused changes in climate while others quickly claim that every weather event is more extreme or more common due to climate change. These extreme positions are roughly aligned with the far right and far left respectively — and discussion of climate science and policy has long been dominated by these extremes.

Climate science is not, or at least should not serve as, a proxy for political tribes. As this series evolves I’ll make arguments backed up by logic and evidence.3 You might or might not find these arguments convincing! Regardless, tell me about it — I invite your challenges, critique, and especially your interpretations of the relevant literature, methods, data, and arguments. Honest brokering is a group effort.

It would be useful as we proceed, but not necessary, to read up on some background on extreme weather events, climate change, disasters, and event attribution that is available here at THB (and the many links to sources therein) — and as the series goes along I’ll provide many links to a diversity of readings:

Thanks for reading! THB is reader engaged and reader supported. Your support makes series like this one possible. Please consider joining the growing community with a paid subscription — supporting independent research and participating in the high-level and informed conversations that take place here at THB.

Even the IPCC uses the sloppy and scientifically incorrect construction — “caused by climate change.” As I’ve explained of IPCC terminology, “climate change” is not a causal agent, it is a statistical characterization of weather variables over time.

Weather event attribution studies have an very interesting genesis in efforts to create climate litigation on the model of tobacco litigation, which requires a putative or plausibly defensible scientific basis in attribution of cause and effect.

While science and politics can never be fully separated, there are better and worse arguments.

I need this and more of this so I don't get in trouble losing my temper and thumping the next person claiming the next weather event is proof of climate crisis. There is no statistical proof over 100 years of measuring that we are experiencing more hurricanes or stronger hurricanes. There is no proof that storms are more deadly. There is evidence that population growth along coastal areas and waterways has significantly increased the number of structures at risk. But that is human stupidity crisis.

As a retired litigation lawyer I can see the benefit to plaintiffs’ litigators of calling something attribution science. But if I understand your column correctly “attribution” is intended to be a synonym for causality while avoiding words like “x causes y”. And the purpose of that semantic device is to induce the reader or viewer or judge into believing that climate change causes increased whatever bad effect, with plausible deniability in cross examination that the scientist witness was claiming causality.