The Unstoppable Momentum of Outdated Science: 2024 Update

Much of climate research and policy is still based on implausible scenarios. Implementing a course correction is well overdue.

Occasionally, I’ll revisit some old posts to provide updates and also to introduce the many new subscribers at THB to things they may have missed. The original 2020 post that I revisit today — The Unstoppable Momentum of Outdated Science — is one of the most read posts ever at THB. Below I update it to 2024. Sadly, it’s central argument remains very much current. The post describes how the very extreme climate scenario (called RCP8.5, backstory here) continues to dominate climate research, despite being outdated and misleading. We knew that in 2020. In 2024, even though the climate community well knows that RCP8.5 is outdated and misleading, peer-reviewed studies using the scenario continue to be published at a rate of ~25 per day. Some of these studies are promoted by climate advocates and the media, and just last week the Biden Administration relied on RCP8.5 to justify its LNG export pause. In the original version of the article below, I lamented that there were in 2020 some 17,000+ RCP8.5 studies in the literature. Today that number sits at more than 45,000 — unstoppable momentum indeed!

A 2015 literature review identified almost 900 peer-reviewed breast cancer studies that used a cell line derived from a breast cancer patient in Texas in 1976. But eight years earlier, in 2007, it was confirmed that the cell line that had long been the focus of this research was actually not actually the patient’s breast cancer line, but was instead a skin cancer line from someone else. Whoops! That means 900 meaningless studies in the literature — representing a huge waste of time, money and effort.

Even worse, from 2008 to 2014 — after the mistaken cell line was conclusively identified — the literature review identified 247 peer-reviewed articles published using the misidentified skin cancer cell line. My 2020 search of Google Scholar indicated that studies continued to be published that mistakenly used the skin cell line in breast cancer research.

The lesson from this experience is that bad science can have momentum and that momentum can be hard to change, even when obvious and significant flaws are identified. This is particularly the case when the flaws exist in databases that underlie research across an entire discipline.

In 2024, climate research finds itself in a similar situation to that of breast cancer research in 2007. Evidence indicates the scenarios of the future to 2100 that are at the focus of much of climate research have already diverged from the real world and thus offer a poor basis for projecting economic growth and carbon dioxide emissions. A course-correction is needed.

A paper of ours in Environmental Research Letters published in 2020 performed the most rigorous evaluation to date (still) of how key variables in climate scenarios compare with data from the real world — Specifically, we look at population, economic growth, energy intensity of the economy, and the carbon intensity of energy consumption. We also looked at how these variables might evolve in the near-term to 2040.

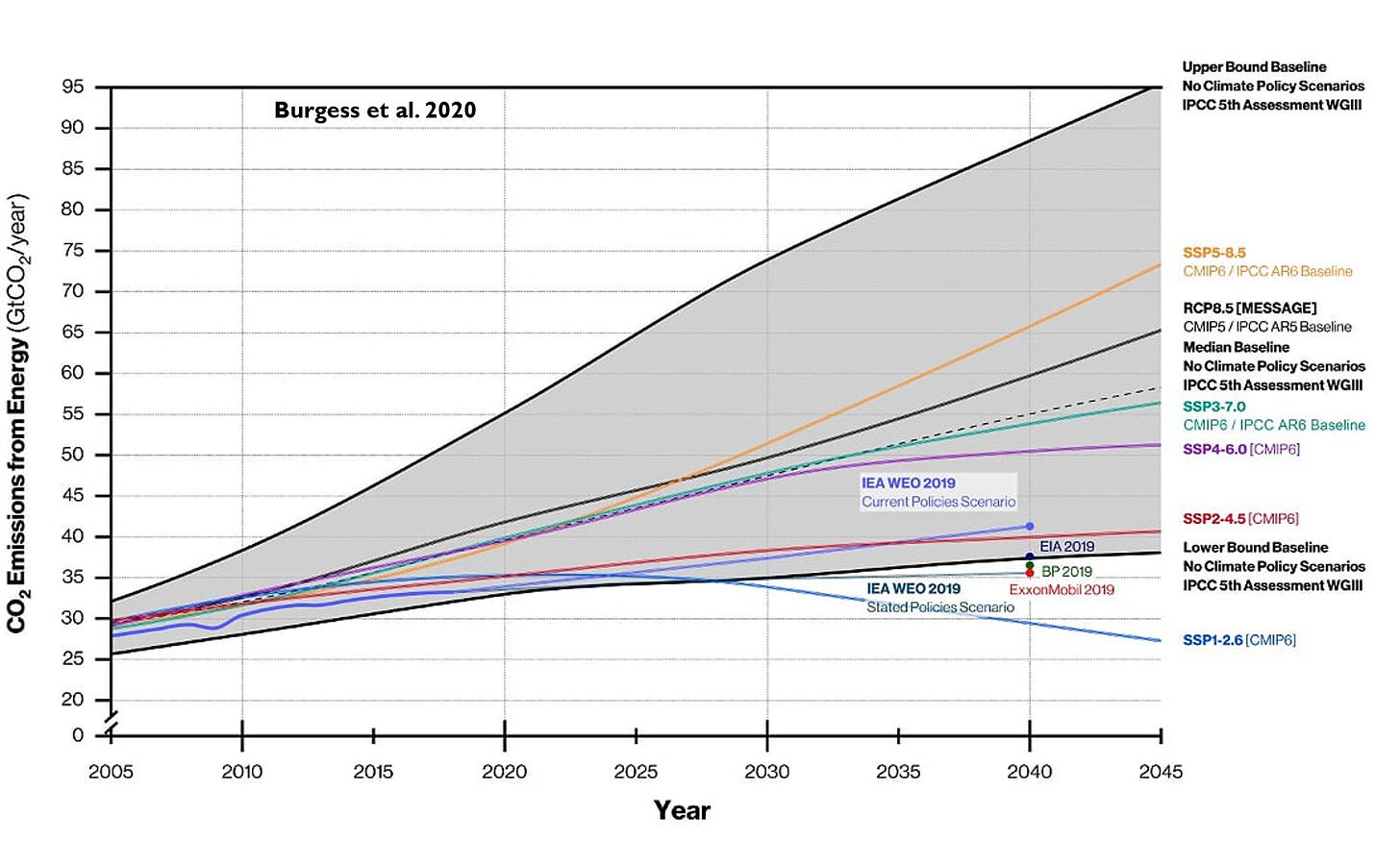

We found — even before the COVID-19 pandemic — that the most commonly-used scenarios in climate research had already diverged significantly from the real world, and that divergence is going to only get larger in coming decades. You can see this visualized in the graph below, which shows carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels from 2005, when many scenarios begin, to 2045. The graph shows emissions trajectories projected by the most commonly used climate scenarios (called SSP5-8.5 and RCP8.5, with labels on the right vertical axis), along with other scenario trajectories. Actual emissions (dark purple curve) to 2019 and the projections of near-term energy outlooks (labeled as EIA, BP and ExxonMobil) all can be found at the very low end of the scenario range, and far below the most commonly used scenarios.

Our paper goes into the technical details, but in short, an important reason for the lower-than-projected carbon dioxide emissions was slower economic growth than expected across the scenarios, and rather than seeing the carbon intensity of energy increasing dramatically around the world, it actually declined in many regions. In short, the scenarios failed to accurately represent how the future would unfold. That’s why most energy scenarios are updated annually, rather than every decade or two as is the norm in climate research.

In 2023, estimates of carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels are just 1.4% greater than in 2019, which means that our 2020 paper and its figures remain current. Meantime, the gap between reality and scenarios has become even wider, and they will continue to diverge into the future. Those old scenarios are obsolete.

Our study built upon a growing literature (which has continued to grow) — notably that led by our co-author Justin Ritchie of the University of British Columbia — indicating that the most-commonly used climate scenarios are well off track and will become increasingly off track. In a widely cited 2020 commentary that builds on Ritchie’s work, Zeke Hausfather and Glen Peters wrote in Nature that RCP8.5 “becomes increasingly implausible with every passing year.” That will continue to be true — forever.

Another paper from 2020, led by Brian O’Neill at the University of Denver and co-authored by many involved in scenario development, has also recognized that the real world and scenarios have drifted apart in the years since the RCP (and SSP) scenarios were first developed. That is of course not surprising, as projecting the future is always challenging. The authors “recommend establishing a process for regular updates” to the scenarios and that key variables in the scenarios “be updated now to be consistent with new historical data.”

Last year, in 2023, a group of researchers seeking to develop the next generation of scenarios to replace the RCPs and SSPs even came up with a phrase to describe the implausible extreme scenarios — “The Emission World Avoided.” The name reflects an effort underway to suggest that the implausibility of the extreme scenarios has resulted because of climate policy. That is untrue as I recently explained, but I probably need to discuss this in greater depth in a future post.

While it is excellent news that the climate community has realized that extreme scenarios are outdated, voluminous amounts of research have been and continue to be produced relying on the outdated scenarios. For instance, O’Neill and colleagues found in 2020 that “many studies” use scenarios that are “unlikely.” They also called for “re-examining the assumptions underlying” the high-end emissions scenarios that are favored in physical climate research, impact studies and economic and policy analyses.

Yet, here we are in 2024 and little if any re-examination has taken place.

As a result of the high prevalence of RCP8.5 studies in the literature, these scenarios are consequently the most commonly cited within scientific assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. For instance, the recent 2021 IPCC AR6 referred to RCP8.5 as “business as usual” many times.

The climate research community is in a similar place to where the breast cancer research community was in 2007. Evidence is now undeniable that a significant amount of climate research has become untethered from the real world. The issue now is what to do about it.

The challenges are large. Consider that in contrast to the 900 articles that misused a skin cancer line as a breast cancer line, our 2020 literature review found almost 17,000 peer-reviewed articles that use RCP8.5. In 2024, that number has grown to more than 45,000 studies! And every day so far in 2024, there have been 25 new studies published using the outdated RCP8.5.

The central role of scenarios across climate research means that there is a huge momentum behind their continued use. A research reset is absolutely necessary and it will be a massive endeavor. Such a reset will require essentially writing off the policy, economic or other real-world relevance of tens of thousands of studies. To be fair, there are reasons to use extreme scenarios in exploratory modeling or theoretical studies, but such uses shouldn’t be confused with practical relevance — just as studies of skin cancer lines should not be confused with breast cancer lines.

Make no mistake. The momentum of outdated science is powerful. Recognizing that a considerable amount of climate science to be outdated is, in the words of the late Steve Rayner, “uncomfortable knowledge” — that knowledge which challenges widely-held preconceptions and which has become institutionalized.

According to Rayner, in such a context we should expect to see reactions to uncomfortable knowledge that include:

denial (that scenarios are off track),

dismissal (the scenarios are off track, but it doesn’t matter),

diversion (the scenarios are off track, but saying so advances the agenda of those opposed to action) and,

displacement (the scenarios are off track but there are perhaps compensating errors elsewhere within scenario assumptions).

Anyone paying close attention to the discussion of RCP8.5 in recent years will surely be familiar with all four of these types of reactions. Such responses reinforce the momentum of outdated science and make it more difficult to implement a much needed course correction.

Responding to climate change is critically important. So too is upholding the integrity of the science which informs those responses. Identification of a growing divergence between scenarios and the real-world is an opportunity — to improve both science and policy related to climate — but also to develop new ways for science to be more nimble in getting back on track when research is found to be outdated.

In 2024 it is fair to ask, how long will it take to correct course?

❤️Click the heart if you think that it is well past time to move past RCP8.5

Thanks for reading! I welcome your comments, critique, corrections, challenges and questions. All perspectives welcomed. THB is subscriber supported and subscriber engaged. The THB comments and discussion is among the very best you’ll find anywhere online. Thank you. Coming later this week — A summary of my talk at AAAS on science diplomacy and a discussion of the regulation of gain-of-function research.

Comment from Stephen Heins:

"After watching the Michael Mann debacle, one can’t help but notice Mann has become relevant again. Stories about the Mann/Steyn case and Op-Ed’s written by Mann are all over Major Media, again.

How can “science” allow him to become the most visible spokesman for the climate crisis, once more? As you have pointed out, old science casts a long shadow with deep roots. "

What I wonder is how many of the people writing papers based on now–impossible (or at least highly improbable) scenarios know that they are doing so.

Either they do know and they are lying to the public in order to chase grant money and tenure or they don't know and they are unfit to write papers about the subject.

Either way, Roger's research here shows us that there are many "climate researchers" who are not only unfit to be that but based on mendacity or incompetence are unfit to be publishing any scientific research at all. Our universities are overflowing with such people.