Long time readers here will be well aware of the problem of outdated scenarios that underpin climate research and the assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The climate community is at long last coming to grips with this problem. The solutions, which are only just now emerging, will revolutionize climate research and policy.

Back in July, I wrote about a workshop held in Reading, UK that discussed the preparation of new scenarios to guide the IPCC’s 7th assessment cycle. Among the recommendations of that workshop was that going forward, the focus should be on “plausible scenarios.” They also emphasized the importance of a “current policies” scenario that projects where the world is currently headed to better inform near-term policy decisions.

At that workshop an influential group of more than 40 scenario experts from the community of integrated assessment modeling and adjacent expertise presented their views on the next generation of scenarios. Yesterday, that group published a pre-print sharing these views for comment.

I encourage you to read the whole paper, and to feel free to offer comments as it moves towards publication — I’ll be offering comments by the 1 November 2023 deadline. Today, I wish to highlight an important implication of the emerging consensus around the importance of scenario plausibility.

The authors characterize the importance of “framing climate pathways” — that underpin a manageable set of scenarios for research and policy. One reason for these is to meet the needs of the climate modeling community:

The need to coalesce on a set of framing climate pathways for the ESMs [Earth System Models] only arises due to the ESMs’ multi-year lead times and high computational costs (Moss et al., 2010). But even for ESMs, a set of framing scenarios does not pre-empt a number of additional investigations, e.g., to allow for both individual modelling groups to pursue their own scenarios or new intercomparison projects to be added later . . .

A second, and primary, reason is of course to inform policy:

The new set of framing climate pathways would need to meet the related key mitigation, and adaptation and loss and damage information needs, by addressing, to the extent possible, important policy-relevant questions . . .

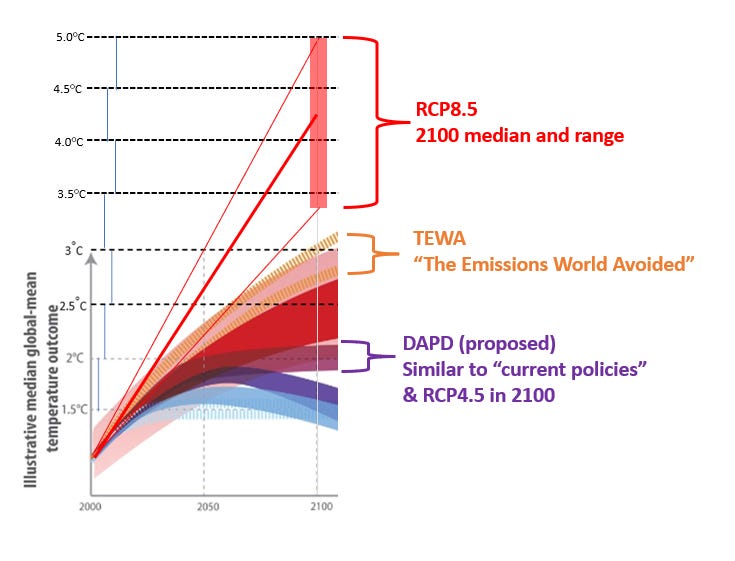

You can see an idealized mock-up of the proposed new family of scenarios in their figure below. Let’s highlight two important points.

First, RCP8.5 has long been out-of-date, but now there is an unquestioned community consensus on this point. In the new scenario space, RCP8.5 (and similar scenarios, like SSP3-7.0) are grouped into a class that we might characterize as counterfactual fiction — they call such scenarios The Emission World Avoided (TEWA). The pre-print has some internal contradictions, as it also states that the TEWA category, “Could lead to the false impression that the difference with this avoided scenario is the exclusive result of successful climate policies . . .”.

RCP8.5 is dead but will no doubt haunt us forever as a scenario zombie. I have no illusions that RCP8.5 and its supporters will go gently into that good night. Even so, “scenario zombie” seems quite a bit more catchy than “TEWA” — but I digress.

A second important point is that the “current policy”-type scenario proposed in the new pre-print has “approximately flat global GHG emissions from 2025 towards the end of century . . .” and is “an approximate depiction of future emissions in the absence of further climate policy action and assuming continuation of “current trends” as of the early 2020s.” The pre-print associates that proposed new scenario with RCP4.5 or SSP2-4.5.

The proposed new scenario implies that if we stop climate policy today, the world is on a RCP4.5 trajectory or less. Good luck explaining how this proposed new upper-end scenario (not worst-case, upper end) is still being promoted by the U.S. National Climate Assessment and countless academic papers as climate policy success.

I annotated a figure from the paper to show the massive significance of the proposed changes to climate scenarios, which is considerably underplayed in their idealized figure. For well over a decade RCP8.5 has been often treated as a reference scenario, centered on more than 4C warming by 2100 — a new reference scenario will center on 2-3C by 2100. This is a huge change in outlook.

Here is why will these new scenarios will revolutionize climate research and policy.

The first scientific question that the authors highlight as crucial to address using the new scenarios is: “What is the timescale of emergence of mitigation benefits?”

While questions of overshoot and zero emissions commitment relate to long-term climate outcomes, the question of the emergence of mitigation benefits in the near-term is of importance to adaptation and loss and damage policy. Outlining and understanding, when, how, and which benefits of mitigation emerge is the basis to inform what impacts of climate change can still be avoided . . .

The authors explain why answers to questions about the timescale of mitigation benefits matter:

Whether we follow a scenario that delays mitigation efforts by 10, 20 or 30 years and reaches net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050 or 2060 or 2070 makes trillion-dollar differences in terms of directing government incentives and private capital (Riahi et al., 2022; van der Wijst et al., 2023), but also in terms of adaptation costs, limits to adaptation, irreversible loss and economic and non-economic costs of anticipated losses and damages (Pörtner et al., 2022). While natural variability in any single year influences global-mean temperatures by ±0.25°C (Box 4.1 in IPCC AR6 WGI, i.e., Lee et al., 2021), climate extremes (Seneviratne et al., 2021) and impacts that reflect long-term, cumulative climate changes (e.g. glacier melt or sea level rise) can be substantially different between a scenario peaking at 1.6°C or 1.8°C in the middle of the century . . .

Can climate research actually differentiate changes in future climate extremes, glacier melt or sea level rise in a scenario that differs by 0.2 degrees Celsius?

I addressed this question just a few weeks ago, based on the work of the IPCC AR6. The answer is no. (I am of course happy to hear from those who think that climate models can actually resolve the implications of such small differences in global temperatures in the near-term behavior of various climate metrics, especially extreme events.)

In fact, climate models are unable to identify differences between a RCP4.5 and a RCP2.6 — current policies vs. policy success — for global average temperature until the second half of this century, at the earliest. It will take much longer (if ever) for far signal emergence for more meaningful metrics, such as the behavior of specific weather extremes.

What happens if climate research cannot meaningly fully quantify the 21st century benefits of mitigation based on new, plausible scenarios that are similar to RCP4.5 (as a high-end) and those similar to RCP2.6 (as policy success)?

That wouldn’t mean that there are no benefits to mitigation, much to the contrary as I’ve long argued. What it would mean is that we would need to adopt methodological approaches other than earth system modeling to quantify the benefits of mitigation — this implies revolutionary change in climate science in support of policy.

For policy and politics, an inability to resolve the benefits of mitigation using climate models would surely result in a search for a broader foundation for supporting mitigation. If so, this would be an incredibly healthy development for the politics of climate, as it would motivate a discussion around a broader base for securing support for mitigation beyond seeking to prevent future weather extremes. This too would be a revolutionary change.

With change comes winners and losers, and we should expect conflict among various communities of experts whose work benefits from such changes and those who work does not. Science, policy and politics all evolve — that’s good. Be ready, change is coming.

I welcome comments and critique. Please share, like repost, restack and get the word out. Also, THB is about to cross 15,000 subscribers! Thanks for reading.

One of the largest water districts in the country, The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California did not get the memo. They voted on September 12, 2023 to use RCP8.5 in their planning. Here is the link to the video where this was discussed and voted on. https://mwdh2o.granicus.com/player/clip/10485?view_id=12&redirect=true&h=7bd3fdeb3d8048682030fa736f6068d3

I would be interested in your thoughts if you have time to review the video.

From the UN Environment Program report -- "This year’s report tells us that unconditional NDCs point to a 2.6°C increase in temperatures by 2100, far beyond the goals of the Paris Agreement. Existing policies point to a 2.8°C increase, highlighting a gap between national commitments and the efforts to enact those commitments. In the best-case scenario, full implementation of conditional NDCs, plus additional net zero commitments, point to a 1.8°C rise. However, this scenario is currently not credible.

To get on track to limiting global warming to 1.5°C, we would need to cut 45 per cent off current greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. For 2°C, we would need to cut 30 per cent. A stepwise approach is no longer an option."

30 percent by 2030 does seem like a significant policy challenge...