Big News: Climate Scenarios are Getting Back on Track

A recent workshop offers excellent guidance but major challenges remain

One of the most important aspects of scientific research is the expectation that errors, dead ends and flawed understandings can be corrected over time. Without self-correction there can be no science. One significant challenge where science meets policy is that self-correction often takes longer than the time frame of important decision making.

Long-time readers here will know very well that the scenarios that underpin virtually all of climate research are badly outdated. Although the community has known this for years, these outdated scenarios dominate the assessments of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), media coverage and policy discussions, giving us a highly misleading perspective on the challenges of climate change and policy opportunities.

Today, I have good news to report.

The climate community — and specifically the CMIP7 ScenarioMIP Scientific Steering Committee — last month held a workshop at the University of Reading, UK where experts discussed initial plans for the next generation of scenarios to inform climate research and policy. The workshop report identified many useful correctives to get climate scenarios back on track.

Before proceeding, let me first explain a bit of the jargon:

Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP). This effort of the World Climate Research Program coordinates climate modeling to inform IPCC assessments. For instance, CMIP5 informed the fifth IPCC assessment, CMIP6 the sixth, and so on. Work is now underway for CMIP7.

ScenarioMIP is the part of CMIP that identifies and coordinates the scenarios that are the foundation on which the Earth system modeling efforts of CMIP build upon.

In its selection and prioritization of scenarios, ScenarioMIP has profound implications for climate research and policy. It is hard to overstate how important the work of this small group is for how we ultimately think about climate and climate policy.

With that, let’s have a look at the CMIP7 ScenarioMIP workshop report on the Pathway to next generation scenarios for CMIP7.

RIP RCPs

One of the most significant recommendations from the workshop is to focus on emissions-driven climate modeling rather than concentration-driven modeling. This is a fairly technical point, and it represents a strong repudiation of the concentration-driven approach to scenarios first adopted in 2005, almost two decades ago.

Here is what the workshop report says:

During the discussions in the various break-out sessions and those in plenary, it was clear that there was a recommendation to run (most) simulations in emission driven mode – in contrast to the use of a concentration-driven approach in CMIP6 (it is an open question whether this includes all greenhouse gases or only CO2). The former leads to a wider range of model outcomes, but that is more representative of the real uncertainty range. The runs would also be more consistent with current modelling capabilities, especially regarding the outcomes of land-based mitigation solutions, heavily dependent on feedbacks that would not be represented in concentration-driven experiments. This will mean that all/most scenarios are to be preferably emission-driven, but concentration data will also be provided for models that can only run in concentration mode.

This recommendation, if followed, would help to correct a massive mistake made by the climate community when it decided to decouple emissions scenarios from climate modeling, setting the stage for the implausible RCP8.5 to dominate climate research (where RCP stands for Representative Concentration Pathway).

Justin Ritchie and I explain:

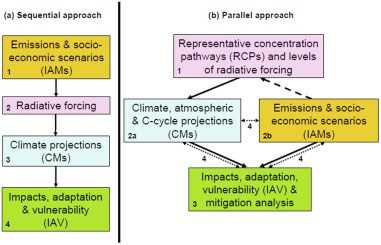

Typically, scenarios and climate projections had been connected in a sequential process, “with socioeconomic and emissions scenarios developed first and climate change projections based on those scenarios carried out next”. . . The development of the RCP scenarios was intended to re-order the scenario development timeline such that the characteristics of radiative forcing would be made available first to climate modelers, in the absence of underlying socio-economic and emissions scenarios which would follow later . . .

The figure below, first published in 2008 and which we reproduce in our paper, illustrates an emissions-driven process on the left and the concentration-driven process of the RCPs on the right.

One main (and likely unanticipated) consequence of the concentration-driven approach was that it eliminated the possibility to evaluate scenario plausibility as a basis for scenario selection and prioritization.

We explain:

Decoupling the RCPs from relevant socioeconomic characteristics therefore served to create a plausibility vacuum which failed the original scenario architecture goals established to ensure plausibility and consistency. The initially selected IAM [integrated assessment model] scenarios were directly intended to “provide useful information on the internal logic and plausibility of each of the individual RCPs” so they could be “judged as plausible story of the future by experts” [32]. As climate model experiments broke away from these archetypal IAM scenarios, there was no longer a definitive means to assess the plausibility of specific RCPs - they quickly became central to climate research and assessment without an accompanying mechanism to evaluate plausibility and consistency.

A return to emissions-driven scenarios would represent an incredibly significant and much-needed course correction for climate research. It would also be consequential for subsequent research and policy. Because it involves change — particularly to climate modeling research — there might be strong opposition from some climate modelers.

“ScenarioMIP should only prescribe plausible scenarios”

The notion that climate research intended to support policy should focus on plausible scenarios would seem to be a no-brainer — after all, a focus on plausibility is central to the CMIP mission. Remarkably, the climate modeling community has never formally conducted an evaluation of scenario plausibility as a basis for its selection and prioritization of climate scenarios. The workshop report reflected that a focus on plausible scenarios was not unanimous, indicating instead that a majority thought that CMIP “should not run implausible scenarios.”

Once there is a commitment to running plausible scenarios, the next question is to define, exactly, the criteria of plausibility employed to identify such scenarios. Plausibility involves technology but also must incorporate considerations of topics such as economics, equity and true energy access. Given the time needed for scenario development it is absolutely essential that CMIP embark on the evaluation of plausibility immediately.

I recommend that CMIP convince Jessica Jewell, Justin Ritchie and Tejal Kanitkar to join their new task forces to assist in developing consensus approaches to the evaluation of scenario plausibility. I haven’t mentioned to Jessica, Justin or Tejal that I’m volunteering them — but I can think of no better group of people to take on such a critical task. Of course, a consensus on approaches does not imply convergence to a single methodology, as there are multiple valid ways to evaluate scenario plausibility. CMIP should organize a major workshop on this topic ASAP, and invite scholars from outside their small community to participate.

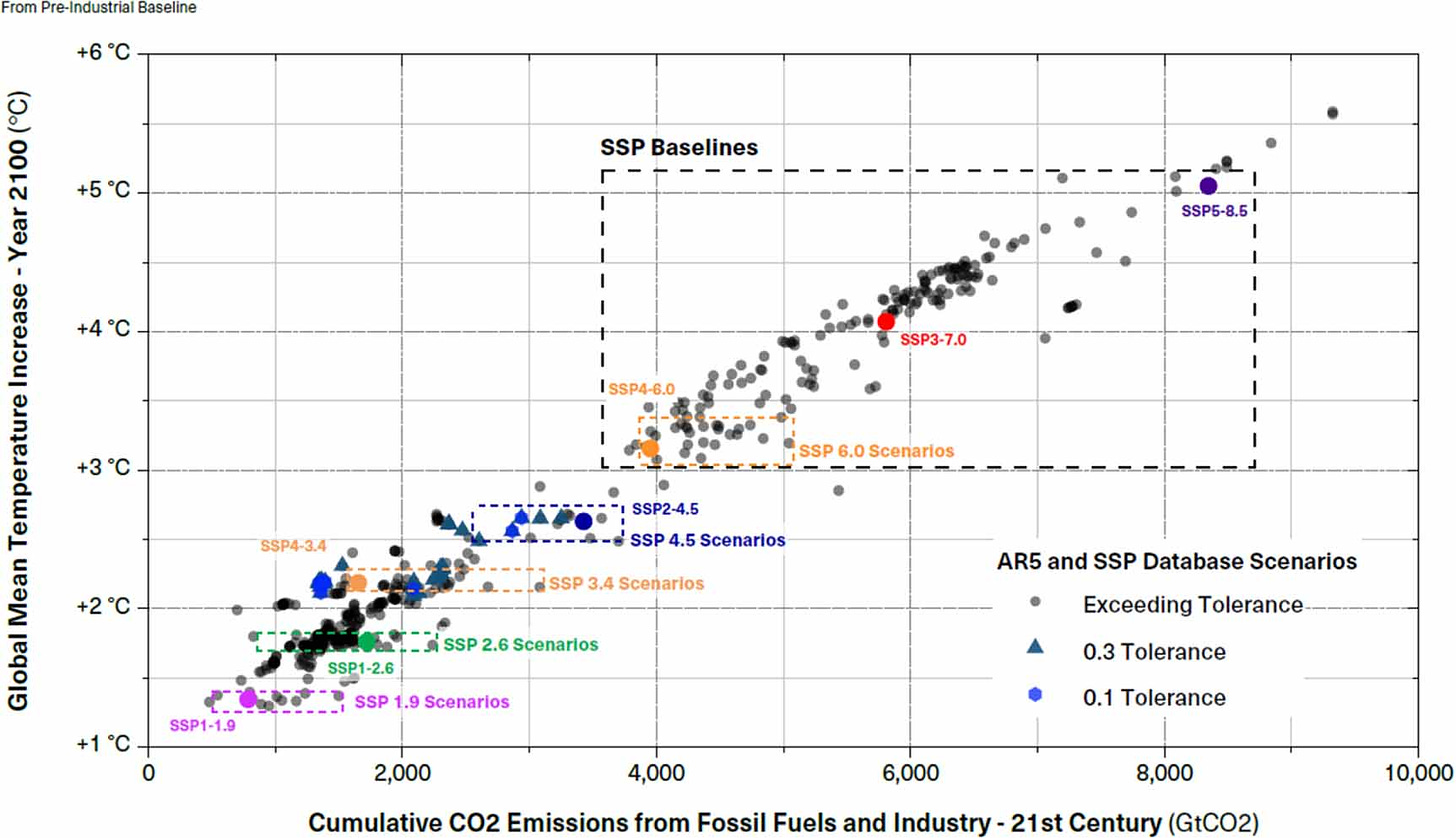

In the short term — meaning for much of the remainder of this decade — the climate research community should identify (more) plausible scenarios from the existing RCP/SSP collection of scenarios. For instance, our research (above) has identified the mostly-ignored RCP3.4 or SSP2-3.4 as median plausible emissions scenarios consistent with observations and near-term projections, with a plausibility range from ~2.6 to ~4.5 scenarios. Our work is not unique and is consistent with a large and growing body of research.

It would be useful for some climate research (versus essentially none today) to start work on 3.4 scenarios, with 4.5 an upper end and 2.6 as policy success. This could happen immediately. The workshop also identified the naming conventions of recent scenarios (RCPs/SSPs) as problematic — I agree, we need to abandon radiative forcing as a naming convention, and this also can happen immediately.

“It is crucial to have a current policy scenario”

It might seem like common sense that climate modeling should focus on projected trajectories of where the world may be actually headed, including uncertainties and the possibility of surprises. Remarkably however, climate modeling has never utilized a “current policy” scenario.

Here is what the workshop says about “current policies” scenarios:

Consideration should be given to two policy scenarios within the current policy range, with careful exploration of the range between them. A second scenario branching off from the current policy scenario could explore the uncertainty range. For this scenario, only legislated policies should be included. The term "current" policy scenario is misleading, and the cut-off date for policies might be around 2025.

The concept of a “current policy” scenario is not always clear or commonly interpreted. For instance, some interpret “current policies” to mean the world as it is today with no future changes. This notion of “current policies” can mislead because the world will change — such a policy is better called “frozen policies.” In reality, assuming no change would more accurately be characterized as a higher-end scenario, given the current direction of travel. Of course, the world could change direction and, for instance, decide to increase carbon dioxide emissions at a much higher rate. But at present that seems highly unlikely.

We’ve now learned well that as the world changes, scenarios must also change. We should fully expect climate scenarios to become outdated fairly rapidly and put in place mechanisms for updating them on the timescales of decision making.

As with plausibility, it is imperative that CMIP start now to identify precisely what is meant by “current policies” and the procedures for regularly updating those scenarios. One thing that we know for sure is that “current” doesn’t stay current for long. This is why energy scenarios are updated on an annual basis. The identification of criteria for determining “current policies” scenarios could be done in parallel with the identification of criteria of plausibility, as these concepts are closely related.

“RCP8.5 is becoming unlikely”

That’s how the workshop report put it — I’d have been a bit more colorful, like “it is past time we buried RCP8.5 in the backyard.” The workshop report correctly acknowledges the need for high- and low-end scenarios and clearly acknowledges the criteria for identify them lies with socio-economic considerations, and not simply the needs of climate modeling.

The report states:

Determining the lowest and highest scenarios should be based on Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) knowledge. The lowest scenario should incorporate other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) beyond climate, such as biodiversity protection and zero hunger, etc. (also in relation to large-scale CDR [carbon dioxide removal]). The scenarios should be feasible. On the high-end, a lower scenario like SSP 7.0 might be useful since RCP8.5 is becoming unlikely.

In considering low-end scenarios the report acknowledges the importance of “feasibility.” This will undoubtedly be a fraught concept — For instance, what happens when we acknowledge truthfully that the 1.5 C temperature target is infeasible?

The report guesses (sorry, wrongly) that a SSP-7.0 scenario might be an appropriate high-end scenario. This is why rigorous evaluation is needed, not guesswork. The SSP-7.0 scenarios are every bit as implausible as the SSP-8.5 scenarios.

There are also the interests and politics of the climate research enterprise to consider. Having high-end scenarios that are consistent with those used in the past allows for comparisons of new modeling results with older results. High-end scenarios also facilitate identifying forced signals of climate change from background variability. In addition, climate advocates wedded to apocalyptic messaging are not going to like a return to plausibility and may resist appropriate high-end scenarios.

The Workshop report acknowledges that identification of appropriate high-end scenarios sits with experts in energy and socio-economics, but also that the climate modeling community has interests here as well:

Determining emissions in the worst-case scenario is a research question for the IAM community. A structured approach is needed to explore aggravating developments that would contribute to high emissions, such as policy rollbacks, high population growth, deforestation, slow energy technology development, etc. SSP3 is a good starting point. If emissions fall within the range of SSP 7.0, it will provide continuity and benefits, such as for CORDEX.

What if appropriate high-end emissions do not reach a 7.0 level? There is no problem with climate modelers focusing on whatever scenario that they think is important in their research. However, care must be taken not to try to smuggle implausible high-end scenarios into CMIP justified misleadingly on their asserted policy relevance. The workshop report is clear that CMIP is focused on plausible scenarios, “leaving idealized/counterfactual pathways to different research exercises.”

The ScenarioMIP workshop report clearly signals that RCP8.5 is RIP. While there is research using RCP8.5 in the pipeline (~20 articles per day still being published), the community should rapidly shift away from its use in research seeking to project climate futures. Peer reviewers take note! Similarly, university press offices and the media should cease hyping RCP8.5 studies immediately. Optimistic, I know!

The ScenarioMIP community deserves our thanks and praise.

They have shown that the self-correcting function of science is alive and well in climate research. But make no mistake, implementing their recommendations will not be easy and may even face opposition. Even under their most optimistic timeline (above) the use of new scenarios in research and by the IPCC would not happen until toward the end of the current decade.

It is thus imperative for the climate research and policy communities to put into place mechanisms to address the continued misuse of outdated climate scenarios so that we can be guided by the best available science.

Climate science is self-correcting, that’s great. I was beginning to wonder. Now, let’s all help it along a bit faster because climate research and policy is too important to be relying on outdated science.

Thanks for reading! I welcome your comments and questions. You can help THB by liking and sharing. If you are not a subscriber please consider subscribing at any level. And if you are a subscriber, please consider a gift for that special someone in your life who would appreciate nerdy posts about emissions-driven climate scenarios! Have a great weekend.

I remain skeptical that this will affect much of the hysteria…

Were you invited to participate in the workshop? Given your recent work in this area I would think it would be a no brainer.

Do "higher ups" get to provide political overlays?

Count me as hopeful but skeptical.