Can Climate Policy Change the Weather?

Assume climate policy succeeds, when we will detect the results

It is January, 2025. President Biden is being sworn into his second term after a landslide victory based on his politically popular declaration of a climate emergency in late 2023. The rest of the world, inspired by the leadership role of the United States, quickly follows along, and the world follows an emissions and climate trajectory long-recognized as climate success — technically called SSP1-2.6.

Plausible or not, let’s start with this imagined future to conduct a thought experiment. Let’s assume that the world follows a SSP1-2.6 trajectory into the future. Based on current understandings as summarized by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, when would we be able to detect the impacts of climate policy success on that actual climate?

A new paper just out prompted this post — Birner and colleagues quantify how accurately we can assess carbon emissions, working backwards from atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide. They assume a world with an emissions plateau (at 2019 levels) and ask when they might be able to identify if countries are misreporting their emissions — For instance, if countries underreport their emissions by a large enough amount, then a gap should open between atmospheric concentrations and the implied emissions.

Their answer is that if a gap between actual and reported emissions was larger than 4.4% over 5 years (or about 1 part per million carbon dioxide) they we could then be 95% certain of misreporting. We can flip this around and ask when would we be able to detect a the effects of decreasing emissions on concentrations — if we were to follow the SSP1-2.6 trajectory.

The answer, according to the SSP Database is 8 to 9 years, or by 2035 (after recentering emissions reductions to start in 2025 rather than 2015 and assuming a baseline of SSP2-4.51). At that point emissions would be >4.4% below the plateau and the difference thus detectable through measurements.

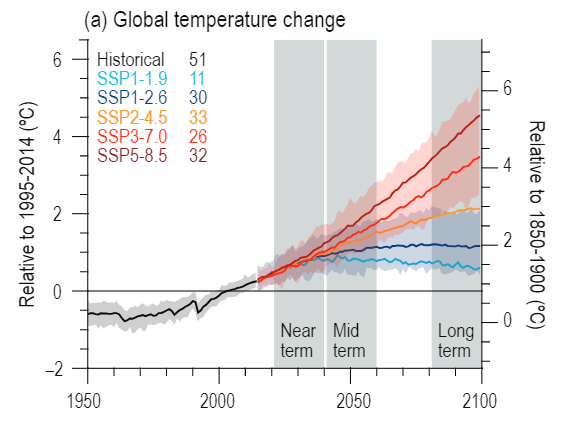

OK, let’s next do global average temperatures. Here the attribution of change to climate policy becomes more difficult. Above, I’ve reproduced IPCC AR6 figure 4.2.a. It shows that the median value for temperature change to 2100 for SSP2-4.5 (in orange) just barely exceeds the 95% range of SSP1-2.6. The 95% range for SSP2-4.5 is not shown, but we can assume it is very similar to the ranges shown for the other two scenarios. That means that we might have ~50% certainty by 2100 that temperatures have changed due to climate policy, and much less certainty in 2050.2

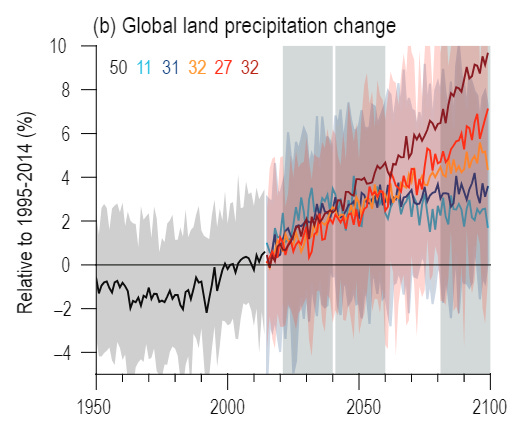

Let’s next do global land precipitation change, shown above. It should be clear from this figure that by 2100 the IPCC does not expect there to be any way to clearly attribute differences in global land precipitation change across scenarios, given the the enormous overlap of ranges across scenarios and in particular for this exercise, the closeness of the medians of SSP1-2.6 to SSP2-4.5.

The IPCC provides other projections, such as for Arctic sea ice and sea level rise that I will not show here, but I’ll encourage you to consider these variables as well, along with your favorites.

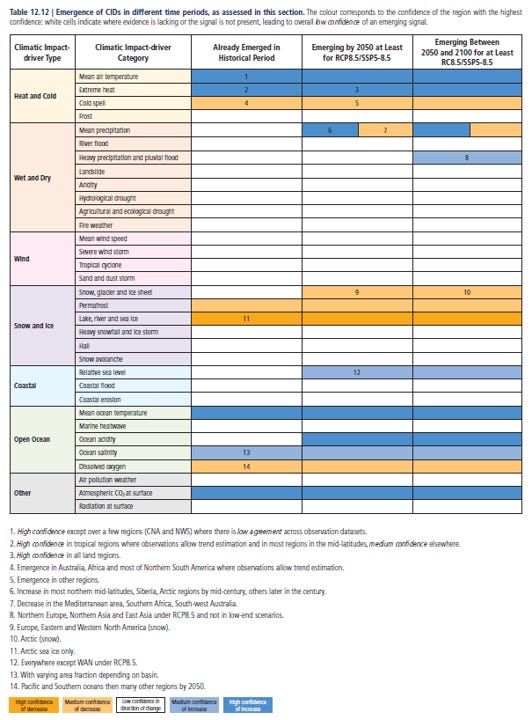

OK, for the last example, let’s do extreme events — like hurricanes and floods. The IPCC helpfully summarizes the expected ability to detect the emergence of a signal of climate change for a range of variables — frequent readers will have already seen the table below.

The figure shows in the white cells — for today, 2050 and 2100 — the expected emergence of signals (at high confidence) for various phenomena under an assumption of the most extreme scenario RCP8.5/SSP5-8.5. Obviously, if we cannot detect the emergence of a signal by 2050 or 2100 under an assumed extreme scenario, then we will not be able to detect a difference between outcomes under SSP2-4.5 and SSP1-2.6.

What does this exercise show? I suggest three lessons.

First, climate policy can indeed have detectable impacts on the global earth system and we can begin to detect these impacts in less than a decade, so perhaps by 2035 for a SSP1-2.6 trajectory that starts in 2025. Make no mistake, mitigation is important and it can work.

Second, for those who expect that climate policy can result in detectable impacts on the climate system — at more-likely-than-not levels of certainty, say, more than 50% — then it will be well into the second half of the century before such attribution is possible for the effects of climate policy on global average temperature and (much) longer than that for global precipitation change.

Third, for those who believe that climate policy can be used to detectably affect the weather that you or I experience, that is simply a fantasy borne from today’s overheated claims of attribution and the fanciful idea that emissions are a disaster control knob.3 In the lifetimes of everyone reading this and our children’s lifetimes, the attribution of changes in extreme weather to climate policy at high levels of confidence is not expected to be possible. Don’t take it from me, that’s straight from the IPCC.

I welcome challenges to this analysis — especially from those experts who may think that climate policies can have near-term, detectable effects on extreme weather. I’m more than happy to publish an argument to the contrary. Challenge issued.

For me, the limited expectation that climate policy can be used to detectably influence the weather results in two conclusions. One is that adaptation will always be the most important approach to prepare for extremes. A second is that mitigation policy must be built upon a much broader foundation for action than just extreme weather.

Thanks for reading. I welcome comments and questions. And I always appreciate likes (little heart above) and sharing across your favorite social media platforms. If you are a subscriber, thank you! If you are not please consider joining the THB community.

A “current policies” trajectory is today expected to undershoot SSP2-4.5 by 2030 or 2050, but that is OK as it makes the analysis below more conservative.

To be clear, climate change can be underway — due to emissions or climate policy — and yet not yet detectable, the subject of a post from last week.

From Mike Hulme:

“The ‘success’ of climate policies can only be captured by slowly unfolding abstract scientific indicators that no citizen can ever experience, such as net carbon emissions, carbon dioxide concentrations, global temperature”

https://mikehulme.org/climate-medicines-do-not-alleviate-the-symptoms-of-climate-change/

"Make no mistake, mitigation is important and it can work."

Huh? You make this claim based ONLY on the possibility of detecting changes in atmospheric CO2 concentration - and NOBODY has shown ANY correlation of CO2 concentrations and global health. In fact, the only real evidence is the opposite - the earth is currently at a global minimum of CO2 in the atmosphere, and if it continues to decline it will almost certainly negatively affect global plant health (and therefore, the health of every living animal on earth).

So, I fail to see how your statement that "mitigation is important" tracks with reality, unless you meant this sarcastically. If we get to that point, we may actually be detecting a global biota collapse of biblical proportions - not quite what the "Climate Emergency" folks had in mind (or maybe it was!)