This is Part 1 of a new THB series on the politicization of the American university. There will be four parts to follow, appearing each Monday in December, 2024.

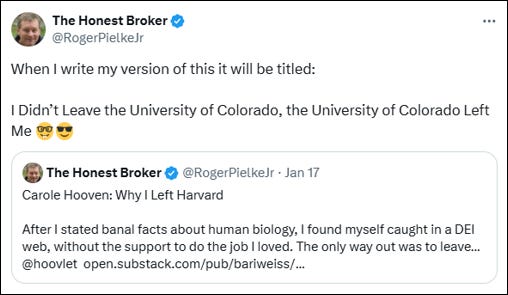

Roger Federer spent 24 years as a professional tennis player. Roger Clemens played 24 years in the major leagues. And at the end of next month, I’ll leave my position as tenured, full professor the University of Colorado Boulder after 24 years on the faculty.1 Roger that!

Leaving the faculty has motivated me to try to make sense of the dramatic changes that I’ve seen in academia since I started grad school in 1990. In this new series I will take a deep dive into one aspect of those changes — the pathological politicization of the American university, and the corresponding loss of public confidence, especially among conservatives.

Before I jump in, just a bit of throat clearing. First, with almost 4,000 colleges and universities across the U.S. — an incredible national resource — my perspective focuses on the 146 very-high research intensive campuses — called “R1” universities — like Colorado. Second, politicization is not the only significant change on campuses in recent decades, there are others — among them, administrative bloat, obsessions with money and football, loss of focus on teaching and research, lack of accessibility, tuition increases, and outside political pressures. However, politicization is a big part of the story, and one we brought onto ourselves. Third, I am a creature of academia, and I deeply value universities as being central to citizenship, expertise, and democracy.2 That means I want them to work — and for everyone. Finally, my views are those of just one professor. Caveat lector!

With that, let’s get started.

Today, I document trends in public perception of colleges and universities and offer some claims about how the overall politics of university faculty have changed. In part two of this series I’ll provide ample data to back up those claims. Together, these trends suggest that higher education in the U.S. does indeed have a serious politics problem.

In 2012, most Americans had a positive view of colleges and universities. A Pew Research Center poll reported that 84% of college graduates believed that going to college had been a good investment, with Republicans at 87% and Democrats a bit behind at 81%. Majorities of both Republicans and Democrats believed that universities had a positive effect on the way things were going in the country.

Since then, public confidence in higher education has plummeted. According to a recent Gallup Poll:

An increasing proportion of U.S. adults say they have little or no confidence in higher education. As a result, Americans are now nearly equally divided among those who have a great deal or quite a lot of confidence (36%), some confidence (32%), or little or no confidence (32%) in higher education. When Gallup first measured confidence in higher education in 2015, 57% had a great deal or quite a lot of confidence and 10% had little or none.

In 2024, polls of public confidence in higher education reveal a stark partisan divide — with 56% of Democrats expressing confidence in higher education and only 20% of Republicans. Confidence in colleges and universities has dropped across the board, according to Gallup:

While Republicans’ attitudes toward higher education have changed the most in the past decade, all key subgroups are now less confident. The changes have generally been similar -- close to the 21-percentage-point drop nationally -- among different educational, racial, gender and age subgroups.

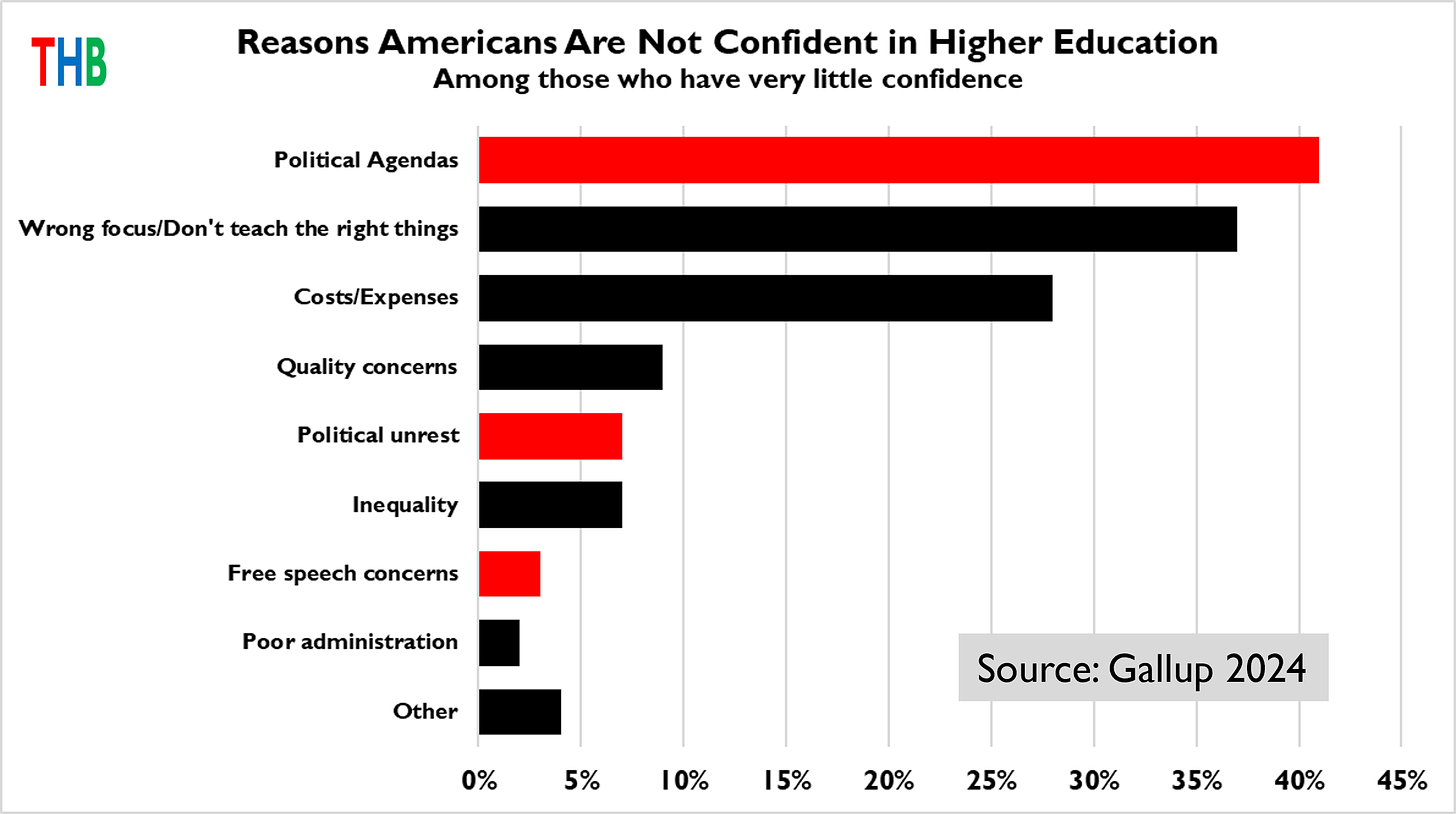

The figure above shows that among those with very little confidence in U.S. colleges and universities, concerns about “political agendas” top the table, with “political unrest” and “free speech concerns” also making the list.

Public concerns over the politicization of university campuses accurately reflect reality. Over my career I’ve seen academia become increasingly politicized with professors and administrators emphasizing political advocacy over research and scholarship.3 For instance, climate change research and education have been profoundly influenced by the rise of climate advocacy in the academy.

Individual faculty members are of course perfectly free to advocate for whatever causes they’d like — that goes with academic freedom, which I deeply value and will always defend. The politicization that I am referring to is an institutionalized politicization of departments, curricula, research, and even entire campuses.

To be perfectly clear — It is not simply the individual or collective politics of university faculty that is pathological, but the institutionalization of a political agenda on campuses. Institutionalization of a political agenda and the corresponding effects would be similarly pathological if that agenda was from the left or right. It just so happens that today’s politicization of academic institutions comes from the far left.4

In a searing article in The Chronicle of Higher Education last week, Michael W. Clune — Professor of the Humanities at Case Western Reserve University — describes what us on campus have observed within many fields:

In reading articles and book manuscripts for peer review, or in reviewing files when conducting faculty job searches, I found that nearly every scholar now justifies their work in political terms. This interpretation of a novel or poem, that historical intervention, is valuable because it will contribute to the achievement of progressive political goals. Nor was this change limited to the humanities. Venerable scientific journals — such as Nature — now explicitly endorse political candidates; computer-science and math departments present their work as advancing social justice. Claims in academic arguments are routinely judged in terms of their likely political effects.

Clune is correct to observe that the push to politicize has not come just from the faculty, but has been encouraged by administrators (many of who come from the faculty):

The primary responsibility for the university’s abject vulnerability to looming political interference of the most heavy-handed kind falls on administrators. Their job is to support academic work and communicate its benefits. Yet they seem perversely committed to identifying academe as closely as possible with political projects.

What are those “political projects”?

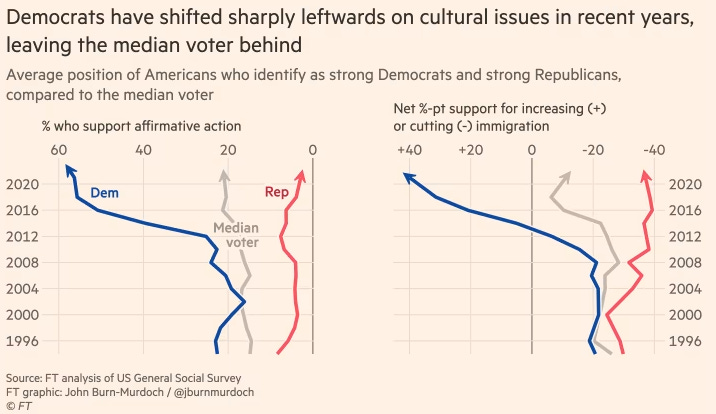

These academic “political projects” are those of the progressive left — and in many cases the most extreme of the political left, such as when climate researchers advocate for degrowth and millenarianism. The image above, from John Burh-Murdoch at the Financial Times summarizes a broader body of research that shows that Democrats — and especially the party’s elite — have shifted in their views far to the left of the median American voter.

Burn-Murdoch concludes:

Whether or not progressives are ready to accept it, the evidence all points in one direction. America’s moderate voters have not deserted the Democrats; the party has pushed them away.

Similarly, university faculty and administrators have both reflected and contributed to this trend, which has played a significant role in declining confidence in colleges and universities among the public, and arguably had an impact on national politics.

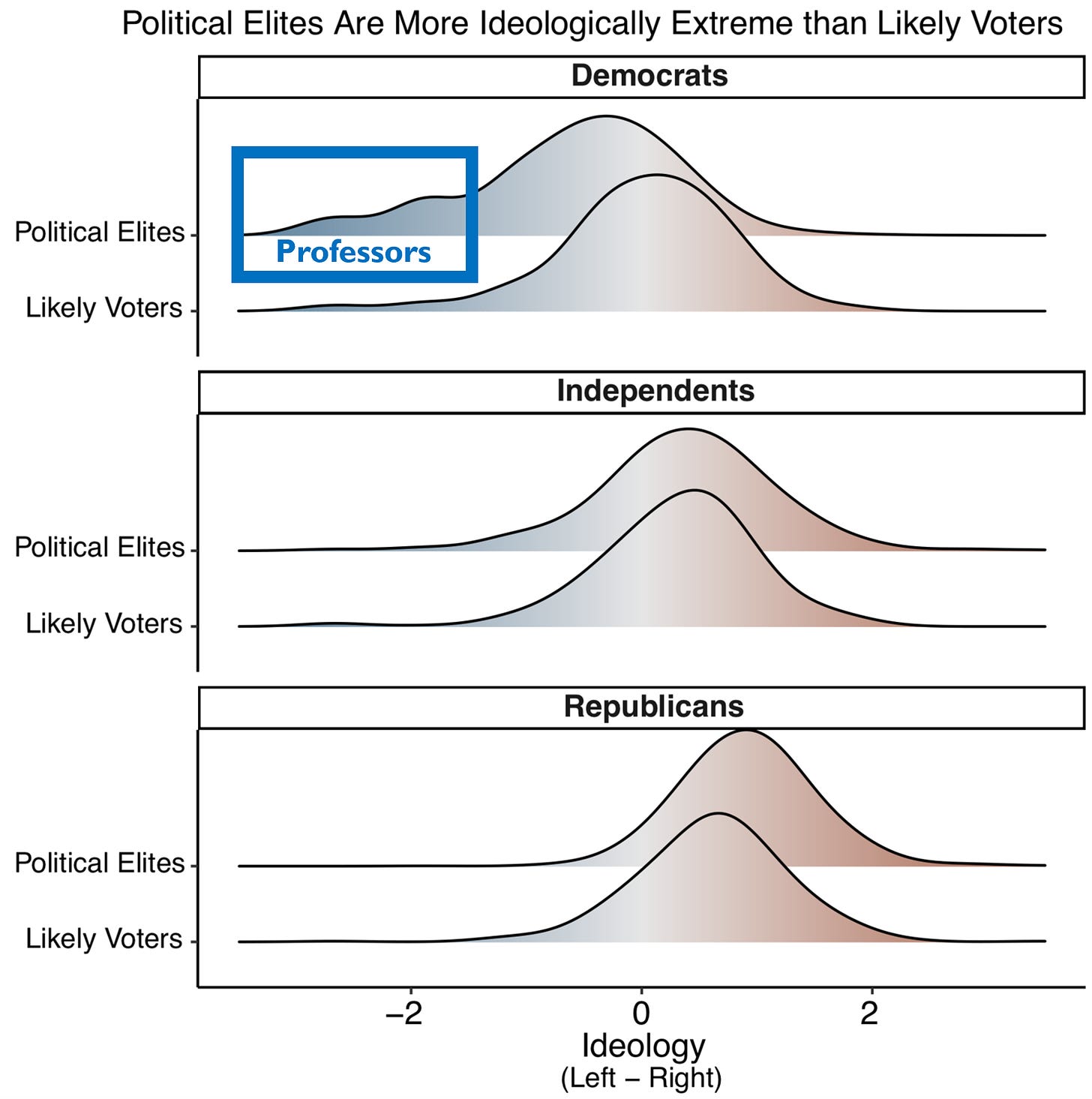

I annotated the figure below, which comes from research by Alexander C. Furnas (Northwestern University) and Timothy M. LaPira (James Madison University). Today, I am not going to share data in support of the blue box that I added to their figure, but in the next post in this series I will: Overwhelming evidence shows that leaders on university campuses hold political views far from those of normal folks. Most won’t be surprised.

In his Chronicle of Higher Education essay, Matthew W. Clune clearly identifies why the politicization of campus is problematic:

What links the work of a professor who conceives of her job as climate activism, to a student-orientation leader teaching that the term “illegal immigration” is a microaggression, to the search committee deciding that this person from a minority group is a good candidate while that one is not? The thread is a shared commitment to a particular brand of partisan politics. If this is truly what the university stands for, if these are our values, then when we are called before our elected representatives to answer for ourselves, what can we say? Colleges have no compelling justification for their existence to give when the opposing political party comes into power. We have nothing to say to the half of America who doesn’t share our politics.

Well, actually it turns out that some professors and administrators do have something to say to those fellow Americans. They tell them that they are misinformed, evil, Nazis even — and warn then that academia in part of a “resistance” and should be “prepared to go to the barricades.” On climate change, they say academics are waging a “new climate war” against our fellow citizens.

In this context, understanding why confidence in U.S. universities has dropped precipitously is not rocket science. What did they expect would happen?

I have plans for four more installments in this series, appearing each Monday leading up to Christmas. Here is what you can expect:

Data on the political affiliations and views of faculty;

How we got here, the long view;

My personal experiences as climate advocacy took root, spilling some tea;

Where from here? Let’s right this ship.

Thanks for reading! THB is building a great community, thanks to you. I invite you to become a paid THB subscriber. Why? To recognize that what you encounter here takes a lot of work. To become part of the THB community. To support me. And also, paid subscribers get lots of goodies as well, including three downloadable books of mine, with more to come. Comments are always welcomed. I’d like to especially invite university faculty and administrators to weigh in — Does this series jibe with your experiences?

Actually 23 years, 7 months. The university has awarded me emeritus status starting January 1, 2025, which means I’ll be Professor Pielke ‘til the end. I appreciate remaining affiliated and have extended an offer to administrators to continue to contribute to the campus.

I’ve had a great career as a university professor, and I leave my position with a strong sense of accomplishment and mostly positive memories. That said, as you’ll read, I do think universities have some problems today that need to be addressed — I experienced some of those problems first-hand.

As readers here well know, my views on climate change science and policy are completely orthodox in the broader context of the IPCC and public sentiment. However, on campus and in academia I have been characterized by some climate activist peers as being on the right, and thus unwelcome in the climate research community. That is a common dynamic — political moderates on campuses are characterized by their peers as being on the right, which reflects a lack of political diversity and a corresponding desire to enforce ideological purity. We will get into those dynamics in the next installments of this series.

Many like to fixate on so-called DEI initiatives as the focus of university politicization. I see DEI as one symptom of a deeper set of issues. On my campus, I never encountered the ubiquitous DEI initiatives, aside from periodic, click-through “trainings.” As a longstanding interest of mine, years ago I conducted an in-depth policy analysis of (the lack of) diversity on the Boulder campus, taught a graduate seminar on the subject, and delivered to university administrators an unrequested detailed report exploring the issue and its causes. It was completely ignored.

When I went away to university at 17, it was to get a good job. Indeed, I graduated and did get a good job.

That has changed. My wife and I fund 529s for all our grandchildren, so far only one has used hers for a Bachelor and Masters. The others, who are old enough, have gone to trade schools (which we also help fund). Guess which one of the group, is the poorest and makes the least?

Economic opportunity upon graduation matters as well. I do not see a bright future for our universities.

Great work, Roger. Keep them coming!

I serve with several other retired faculty members on the advisory board for one of the new colleges trying to provide non-political education focused on learning (specifically Reliance College). While my retirement was for health reasons, a number of the other advisors retired to escape the "woke" environment.