Earlier this year, at its annual meeting the American Meteorological Society announced that the organization was signing a climate “pledge” along with EarthXTV, promising that it would work to mitigate climate dis/misinformation:

“Addressing climate change must be a top priority, if humanity and all life is to thrive. Therefore, the undersigned scientific societies and media organizations commit to working together to inform all audiences about the challenges and opportunities facing humanity at this point in the 21st century by signing a joint pledge to work together on all fronts from a science-based position to mitigate today's prevalent dis/mis-information about climate change.”

More than 15 other scientific societies signed the pledge — including the American Geophysical Union and meteorological societies from 9 other countries and regions. What exactly the pledge means in practice is not clear, but battles over misinformation are typically about politics more than information.

Scientific societies are membership organizations which are created to allow people to associate with others with similar interests or in similar professions. One function of membership organizations is to advance the shared interests of their members, and such advancement typically includes participating in politics, whether through communication and advocacy or more formally as lobbying.

Consider the third “A” in the largest scientific society in the United States, the AAAS — the American Association for the Advancement of Science.1 Scientific societies are interest groups which are absolutely essential to the functioning of a healthy democracy — exactly as envisioned by James Madison in Federalist 10.2

One answer to the question of whether science societies should take political positions in the form of pledges to this or that cause, or even endorsements of political candidates or platforms is — Sure, go for it. Interest groups comprised of likeminded people appealing to their fellow citizens and government for outcomes they believe to be in their group interest is the lifeblood of democracy.

However — and it is a big however — scientific societies also perform public interest functions that may be compromised by their special interest political positioning. Specifically, I am referring to the role that scientific societies play in overseeing peer-reviewed journals where scientific claims are made, challenged, debated, and collectively make up a significant part of what we consider to be scientific knowledge.3

The pursuit of special interests by a scientific organization could compromise its effectiveness as a public interest forum, in the words of Nature’s mission statement:4

“. . . to ensure that the results of science are rapidly disseminated to the public throughout the world, in a fashion that conveys their significance for knowledge, culture and daily life.”

Nature does not exist to serve only its subscribers or even the broader scientific community, but “the public throughout the world.” I assume that editors of virtually all scientific journals would agree.5

This creates a situation of potential conflict — Scientific societies exist to serve the special interests of their members whereas the journals that they host exist to serve the common interests of the public.6 What happens when special interests conflict with common interests?7

We do not have to speculate on the answer.

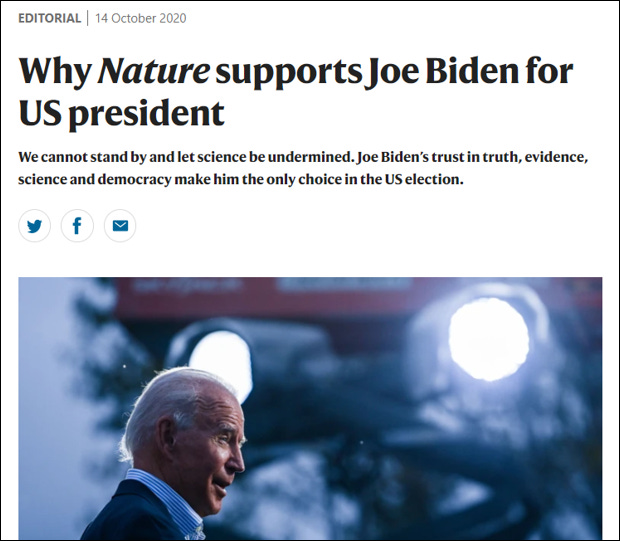

In 2020, Nature endorsed candidate Joe Biden in the U.S. presidential election.8 Several years after, Floyd Jiuyun Zhang of Stanford University explored the consequences among U.S. citizens of the endorsement on measures of trust in Nature and the broader scientific community.9

What Zhang found should have set off alarm bells in any editorial board or scientific organization looking to become more political:

This study shows that electoral endorsements by Nature and potentially other scientific journals or organizations can undermine public trust in the endorser, particularly among supporters of the out-party candidate. This has negative impacts on trust in the scientific community as a whole and on information acquisition behaviours with respect to critical public health issues. Positive effects among supporters of the endorsed candidate are null or small, and they do not offset the negative effects among the opposite camp. This probably results in a lower overall level of public confidence and more polarization along the party line. There is little evidence that seeing the endorsement message changes opinions about the candidates.

Zhang found that the endorsement of Joe Biden by Nature made polarization worse, decreased trust in the scientific community, and did not change views on the candidates. Other than that, how was the play Mrs. Lincoln?

Nature responded to the study by doubling down on its commitment to make political endorsements, regardless the consequences:

. . . the study does question whether research journals should endorse electoral candidates if one implication is falling trust in science. This is an important question, and there are, sadly, no easy answers. The study shows the potential costs of making an endorsement. But inaction has costs, too. Considering the record of Trump’s four years in office, this journal judged that silence was not an option.

Nature’s October 2020 editorial was an appeal to readers in the United States to consider the dangers that four more years of Trump would pose — not only for science, but also for the health and well-being of US society and the wider world. . .

The fact that just under half of U.S. voters who voted in 2020 voted for Donald Trump is clear evidence that the special interests of Nature (a London-based journal) conflicted with the interests of almost half of those who voted.

What action by Nature might have been more consistent with common interests? Not endorsing a candidate.

By not endorsing a candidate the common interests being served would have been helping to sustain and reinforce trust in the scientific community and not serving to compromise or polarize that trust. For scientific organizations, appeals to special interests at the expense of common interests is a choice.

Scientific membership organizations have every right to act as politically as their members desire — though here too I’d urge evidence-informed caution. But scientific journals are different, simply because they have a public interest focus.

Stronger institutional firewalls are needed between societies and the journals that they host. Journals have one job, and that is to provide a forum for publishing peer-reviewed research, which I’d note, will in individual papers will often reflect political agendas, arguments, and biases.

Journal editors should eschew the lure of and demands for playing interest group politics and stay focused on their core mission — that will better serve both common interests and the special interests of the scientific community to serve all people, no matter who they vote for.

❤️Click the heart if you will vote for Joe Biden, someone else, or if you can’t even vote in the U.S. election!

Thanks for reading! I welcome your comments, critique, alternative points of view. THB is reader supported and reader engaged.

Among its functions, AAAS publishes the Science family of journals.

Of course, scientific societies exist in countries that are not democracies.

There are of course many other forms of expert knowledge beyond that found in scientific journals.

Nature is part of a for-profit corporation.

But if any editors reading this disagree, let me know!

Here I am using “public interest” and “common interest” interchangeably.

One seemingly easy way out of this potential conflict would be to claim that what is in the special interests of the/a scientific community is or should be also defined as the common interests. Don’t go there.

Full disclosure: I voted for Joe Biden in 2020 and I will again in 2024.

Not quite certain how you can write this article and then have some kind of a clickable heart at the end of the article that apparently supports Biden. Then in the footnotes you announce your own support of Biden. This makes me respect you opinions just a little bit less.

Roger confirms the tribal nature of politics.

It is Democrats and democratic affiliated "scientists" who are struggling mightily to shut him down, some even want to jail him for the inter-generational crime of "posting data" and "fostering open debate".

Its his team that is corrupting and destroying science, everything he rails against here on THB.

They are the entire reason there is a THB in the first place.

And yet still, you beg for more.

People are infinitely capable of self abuse.