Pielke's Weekly Memo #12

Magic Beans as climate policy, United in (Bad) Science, Pakistan's floods, a new talk, recommended readings and goals of the week!

Now free to read (29 Sept 2022)

Lots to cover this week, so I’ll keep things tight and moving.

Magic beans as climate policy

I’ve noticed a recent increase in what I’ll call “magic beans” thinking as climate policy. It is exemplified by aggressive calls for the impossible, such as in the Tweet below from U.N Secretary General António Guterres demanding that the “current fossil fuel free-for-all must end now.”

Presumably by “current fossil fuel free-for-all” Guterres is referring to countries that are stocking up on fossil fuels for the coming winter and taking every step possible to ensure security of supply. Energy services that make possible modern life are due in large part — more than 80% in 2021 — to the consumption of fossil fuels. Recognizing this fact doesn’t make one a fossil fuel shill or a climate denier (both of which I was called this week after pointing this out) — it makes one a card carrying member of the reality-based community.

There are long-term goals to reduce dependence on fossil fuels dramatically, even completely. These goals are worthwhile as they will reduce environmental impacts, lower energy costs and increase energy security. But they can’t happen immediately. Calls for abandonment of fossil fuels now reflects “magic beans” thinking, and not anything remotely related to realistic or pragmatic policy. We might expect such demands from passionate but uniformed campaigners, but we should expect better from the Secretary General of the U.N..

Before long I’ll do a full post on “magic beans” thinking as climate policy. Meantime, please send me examples of demands for the impossible as you encounter them.

And now the jump to United in (Bad) Science, Pakistan's floods, a new talk, recommended readings and goals of the week!

United in (Bad) Science

Earlier this week a group of organizations coordinated by the World Meteorological Organization issued a report sampling from a series of other recent reports — a clever way to re-generate some headlines, I suppose.

The new report is titled United in Science: We are headed in the wrong direction. Overt political advocacy by scientific organizations and international research projects is commonplace these days. Those engaging in such advocacy should at least have their facts rights. That is not what happened here.

This report includes the following false claim:

“The number of weather, climate and water-related disasters has increased by a factor of five over the past 50 years”

This claim is completely false and depends upon presenting an increase in the reporting of disasters as an actual increase in disasters. Debarati Guha-Sapir, of the Centre for Research in the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) at the Université Catholique de Louvain, has spoken about the misuse of the EM-DAT database housed at CRED.

Even today we have people quoting us saying that the EM-DAT database shows that disasters are increasing in an alarming way. It’s not increasing in an alarming way. I think that’s wishful thinking. . . We’ve said at our press conference that there’s not been an increase . . . Nobody wants good news.

Here is what the data actually show for the period for which CRED believes the data to be reliable and complete. Good news — so far this century disasters are down. That trend continues well into 2022, according to CRED.

WMO has repeated this false claim repeatedly in recent years and risks damaging the credibility of what is an important institution.

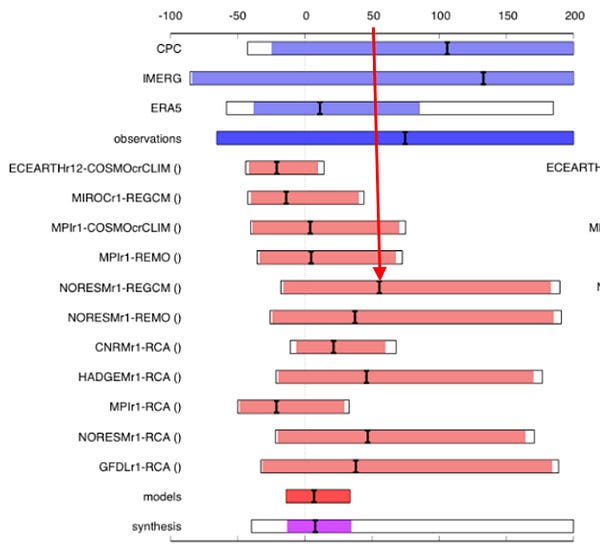

Slides from my Talk this Week at CICERO

Earlier this week I gave at short talk at CICERO here in Oslo. The talk was focused on introducing me and my work to climate researchers at the center. There was a good discussion afterwards.

I plan on sharing slides from my talks here, as a resource for others and to stimulate discussion. You can download a PDF of this deck here. Comments welcomed!

Pakistan’s Floods

This could easily be a full post in my ongoing SERIES: What the media won’t tell you about . . . The release yesterday of a report by the World Weather Attribution (WWA) project has been accompanied by a flurry of misleading headlines and grossly inaccurate reporting. Since WWA advertises that they are in business to generate headlines, perhaps this is not all bad.

For those of us who think science should be reported accurately, the misinformation is troubling. The Guardian is the worst offender that I’ve seen, as I memorialized in the Tweet below.

One need simply to read the report to see that the authors were unable to show attribution, instead hypothesizing that a relationship “could” exist between greenhouse gas emissions and heavy precipitation in Pakistan, but that it could not be shown at present.

Here is what the report actually says:

[L]ong-term variability, or processes that our evaluation may not capture, can play an important role, rendering it infeasible to quantify the overall role of human-induced climate change.

Very clear. Reporting on extreme weather events should not be this bad.

Some recommendations to read and listen to

Being on sabbatical I have more time than ever to read promiscuously. It has been great.

Here are a few things that crossed my desk this week that I’ll call to your attention to — and I invite you to do the same in the comments:

The final report of the Lancet COVID Commission and a very good interview of its chair, Jeffrey Sachs

As a follow-up to a discussion THREAD that I opened up here earlier this week, here is an interesting article on The growing gap between excess and covid mortality — more to come on this interesting subject in coming weeks and months

A fascinating investigative story by Politico and Welt on How Bill Gates and partners used their clout to control the global Covid response — with little oversight

A new season just kicked off of The Received Wisdom podcast with Shobita Parthasarathy and Jack Stilgoe — two of my favorite colleagues. Fascinating discussions for science policy wonks.

Another excellent podcast for science policy wonks comes from SAPEA (Science Advice for Policy by European Academies) — this episode talks with Janusz Bujnicki on developing science advice in Poland: From Brussels to Warsaw, Professor Janusz Bujnicki is helping to shape the future of scientific advice.

Finally for this installment, a new paper by Gustafson et al. titled, The durable, bipartisan effects of emphasizing the cost savings of renewable energy — I like it of course because it reinforced the importance of the “iron law” of climate policy. You can also see a good Twitter thread by its lead author here that offers additional reading.

Goal(s) of the Week

Finally, a whole bunch of goals this week. This is the highlight video from my son’s 2021 high school soccer season, for which he was voted a United Soccer Coaches Academic All-American. Proud dad here. Enjoy!

This is a good post, and I like your "magic beans" analogy. However, I have two comments. First the link to the PDF file of your CICERO talk did not work for me, sending me instead to the CRED homepage.

Second, and I apologize for this nit-pick, but your graph is incomplete. It lacks a label for the ordinate. While one could infer from the title that is it showing "weather and climate disasters" versus year, it is unclear here how weather relates to climate. My understanding is that climate is an average of weather. Does the graph show this average?

Where can I go to gain a better understanding of the supporting data for this graph? I am curious about how they define "disaster." I live in the midwest, where drought has been prevalent for much of the past decade. Is "drought" the disaster, or is the lowered crop expectations/harvests the disaster. There have been times when yields have been great in spite of heat or absence of precip.

"Magic beans," indeed. More like smokin' bad weed!

While it may be useful to talk about how scientists should be advising decision-makers, it ultimately is mis-attribution [pun intended] of the real problem: the lack of leadership throughout the Western world. Facts don't matter; science doesn't matter. All that matters are social media and the polls. Will I take heat if I decide X? Then I won't. Will the trolls come out in force if I look for compromise? Then I'll turn my eyes away even from the other side's good ideas. Will my standing in the polls nosedive if - like Bastiat's good economist - I take action that will be negative in the short term, but ultimately be positive? Then I'll sit on my hands.

We certainly need leaders who will listen, and people who will talk sense to them. But most importantly, we need leaders who will lead - make those hard decisions, take those tough actions. The best advice in the world is meaningless if the decison-maker is too cowardly to take it. And, sadly, we seem to have substituted cautious cowardice for leadership in our political arenas, in our university administrations; in fact, in all too many of our public institutions.