Partisan Professors

Politicization of the American University, Part 2

This is Part 2 in the THB series, Politicization of the American University. You can read Part 1 here.

Faculty in U.S. universities overwhelmingly hold views on the political left. That probably won’t be news to most THB readers. Today’s post documents just how extreme today’s left-leaning ideological uniformity has become among professors and shows that in the past, across disciplines faculty were much more politically diverse.

The lack of diversity among professors is problematic for both education and research, ostensibly the overriding purposes of universities. A more insidious and fundamental issue is that some extremely partisan faculty (and administrators) have commandeered university departments, centers, institutes — even entire campuses —and repurposed them for political advocacy.

Diversity of opinion within the framework of loyalty to our free society is not only basic to a university but to the entire nation. —James Bryant Conant 1948

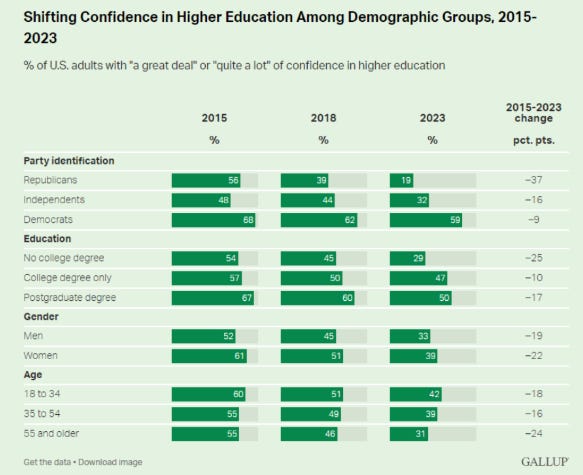

Plummeting confidence in higher education among Americans (see figure below) reflects a widespread belief that universities have become institutionally politicized in ways that are contrary to the values and politics of most citizens. As you’ll read below, such beliefs are backed by evidence. Universities are supposed to serve common interests, not the narrow political agendas of the faculty.

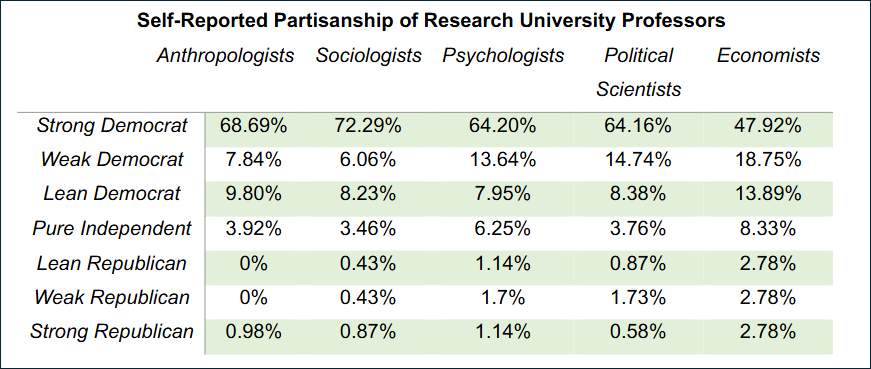

Data on the contemporary politics of professors shows that university faculty as a group hold views very different than most Americans. For instance, a 2020 survey by Joshua Koss, a political scientist at Michigan State University, of tenure-track faculty across 67 universities that are members of the American Association of Universities revealed a striking partisan imbalance across the main social science disciplines, shown in the table below.

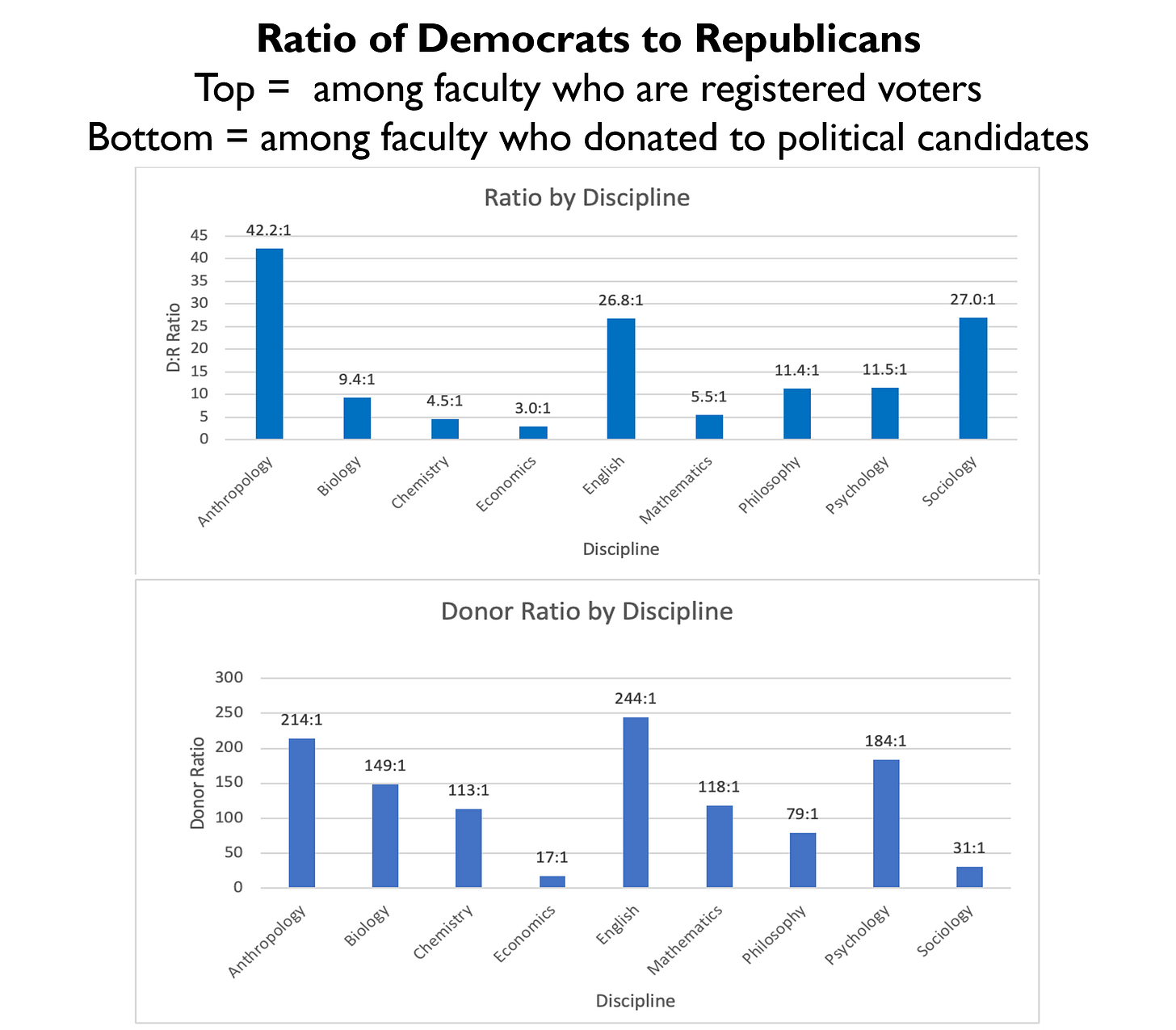

A similar survey was published in 2020 by the National Association of Scholars of more than 12,000 tenure-track faculty in the top-ranked universities in each state, based on publicly available information. Results are presented as a ratio of Democrats to Republicans among faculty who were registered voters and who had donated to political candidates. The results show that among those registered to vote by party ID, professors are almost all Democrats. That ratio is even stronger among those who donate to campaigns, as shown in the figure below. Consider that chemistry, a discipline far from partisan politics, has a ratio of 113 donors to Democrats for every one donor to Republicans.

A 2017 analysis by Samuel Abrams of Sarah Lawrence College showed that the political orientation of faculty members had moved to the left over several decades, with a notable increase starting about 2004. In contrast, the ratio of Democrats to Republicans among students and citizens changed little over the same period.

These data show that university faculty are overwhelmingly on the political left, across all disciplines,1 and the proportion of left-leaning faculty has steadily increased in recent decades.

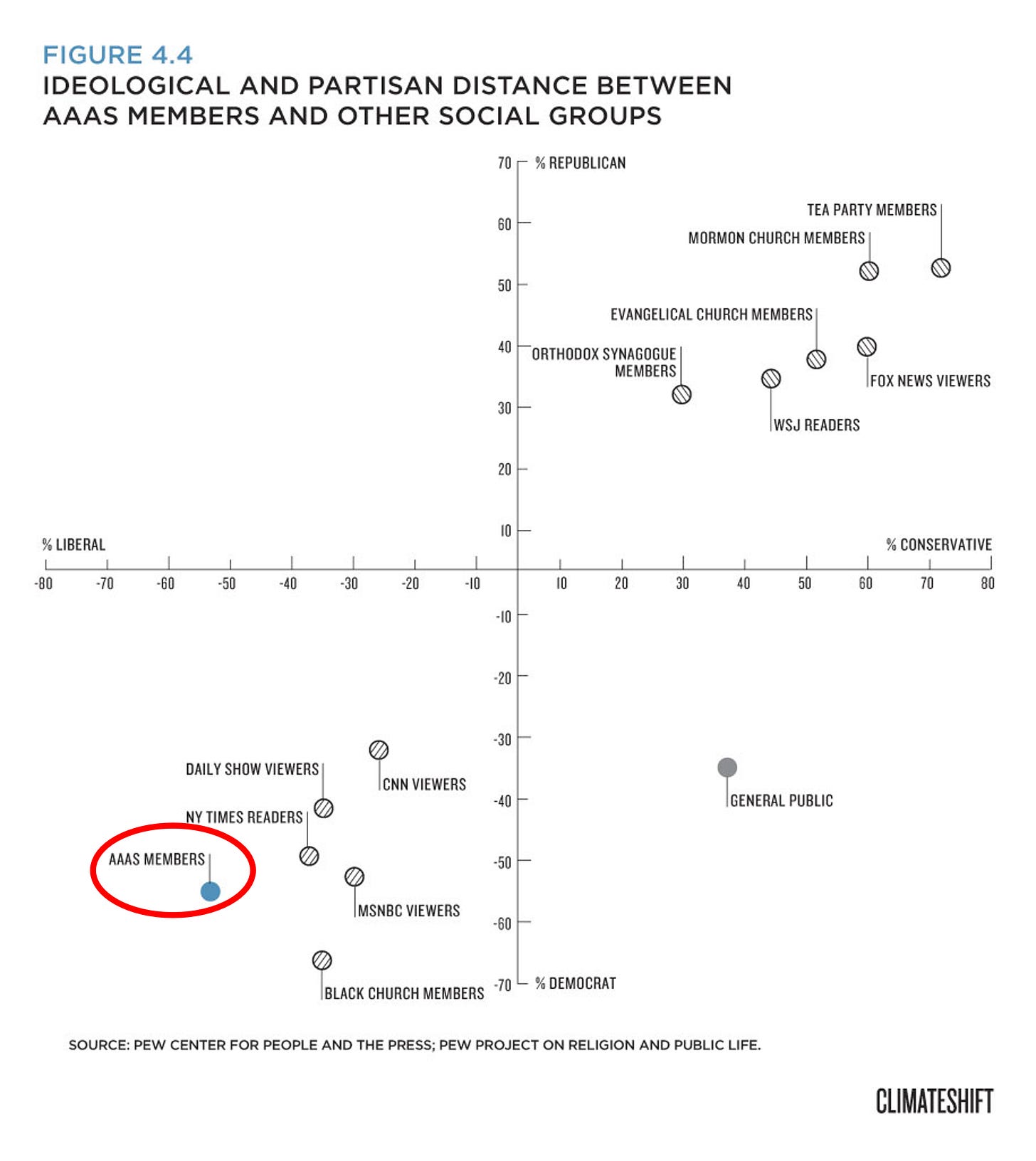

Let’s take a look at one more dataset, from the work of Matt Nisbet of Northeastern University on the political and ideological views of members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) from back in 2011.2 The figure below shows that in 2011 AAAS members self-reported ideological views and partisan affiliations that were more liberal than black church goers, more Democratic than MSNBC viewers, and combined partisanship/ideology comparable only to Tea Party members on the right.3

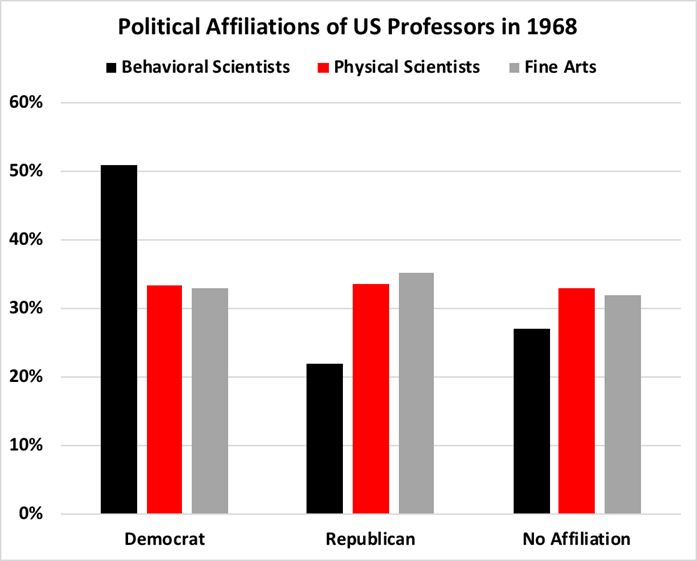

The extreme leftward lean of the academy has not always been the case. The figure below, shows survey data on the political affiliation of professors published in 1968. Behavioral scientists leaned left,4 but physical scientists and those in the fine arts were evenly distributed between Democrats and Republicans and No Affiliation. Even among behavioral scientists more than 20% reported being Republicans.

Another 1968 study of the politics of university faculty also found that social scientists tended to be on the left, whereas a majority of botanists, geologists, mathematicians, and engineers characterized themselves as conservatives. I am not aware any recent research that shows any academic discipline with a majority of faculty self-describing themselves as conservative — It’s not even close.

Writing in The Independent Review (Winter 2022/2023) Phillip Magness and David Waugh concluded:

It is now a clear empirical fact that since the early 2000s, trends in faculty political identification have moved sharply leftward, yielding a 15 percentage point shift in as many years. Accompanying this shift, faculty and university administrators have increasingly prioritized overt political activism as a primary emphasis of classroom instruction. The changing ideological landscape has not only made nonleft constituencies feel increasingly unwelcome on campus—it has also started to materialize in hiring discrimination against faculty applicants with nonleft perspectives in several of the most politically skewed disciplines.

Writing in 2017, Samuel Abrams characterized why ideological uniformity can be problematic for teaching and research:

The problem here is actually quite simple: When almost everyone in a field or department shares the same political orientation, certain ideas become orthodoxy, dissent is discouraged, errors can go unchallenged, and these orthodoxies inhibit scholarly inquiry. Groups of scholars whose worldviews are in broad agreement are more prone to confirmation bias and less likely to challenge scholarship that comports with their views.

This ideological narrowing is dangerous not just for the creation of new knowledge and research, but also because it does a disservice to the very people we professors are trying to educate and lift upward. Ideological homophily all but assures that students will go out into the world less able to see the world as it really is, and poorly equipped to defend their worldview. As teachers, we fail in teaching students how to think. When students are shielded to divergent view points and counter-arguments on the issues that are more salient to them, the students understandably become confused and angered by others who see the world differently. This diminishes our national discourse and frays our civic bonds.

Moreover, if academia is ideologically far removed from the people as a whole, this can weaken or sever the institutional bonds of trust that exist between it and the broader society.

I will take the argument even further: It is not just teaching and research that suffers from the narrowing of political perspectives on campus.5 In some cases, likeminded faculty have repurposed universities for political advocacy in service of their favorite causes, losing sight of why we have universities in the first place, and contributing to the loss of public confidence.

In Part 3 of this series next week I will offer an explanation for the reasons underlying these trends — which start with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

“♡ Like” this piece to help get THB in front of more readers!

I have plans for three more installments in this five-part series, appearing each Monday leading up to Christmas. Here is what you can expect:

Part 1: The Problem

Part 2: Partisan Professors

Part 3: How we got here, the long view

Part 4: My personal experiences as climate advocacy took root, spilling some tea

Part 5: Where from here? Let’s right this ship

Thanks for reading! Comments, questions, critique are all welcomed. I especially invite currently-active faculty to offer their views on this topic. As most of you are aware, I’m in my last month as a tenured full professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, and while the issues raised in this series are not the main reason I am leaving academia, they certainly have made it much easier. THB exists because of your support!

I don’t show the data here, but a recent survey found a similar ideological bias in schools of public policy as well.

AAAS members are not all university faculty, of course.

It’d be great to see what this data looks like today.

The “behavioral sciences” include many of the disciplines that today we call the social sciences.”

Note that I am a champion of academic freedom: Individual faculty are free to advocate for whatever positions, policies, or politics that they want. When such advocacy becomes institutionalized — formally or informally — we have a problem.

I contend that America's rapidly-diminishing leadership in the sciences and engineering is due, in part, to the rigid orthodoxy at universities.

For example, in my field (weather science) NOAA funds a great deal of research. As Roger has previously documented, NOAA has morphed from a science organization to a climate alarmism advocacy organization. So, even though NOAA is failing at its most important mission (most recently: delayed flood warnings for the southern Appalachians when Helene's flooding threatened), NOAA gets rigidly defended by the people who should be helping contribute to its future.

No one wants to upset the funding apple cart, especially when they share your politics.

To which extend the survey comparisons over the years is also influenced by a shift of meaning for the label "democrat" or "republican"? These denominations have no stable definition (if they have any).

Asked differently: would a democrat of the 60s (or during the cold war) recognize himself or herself as such in 2024? Same symmetrical question for republicans.