Today’s guest post is by Andrea Saltelli, of the UPF Barcelona School of Management in Barcelona, Spain and the Centre for the Study of the Sciences and the Humanities at the University of Bergen, Norway. We welcome your comments and discussion! —RP

Our new paper published in WIRES Climate Change questions the logic and the opportunity costs of building a digital replica of the planet — inclusive of its human population. These-much hyped projects — such as Destination Earth in Europe (DestinE), and similar initiatives in the US and elsewhere — are rapidly being implemented with no serious discussion or debate of how these efforts look through the lenses of system ecology, sociology and political sciences. Better and more equitable use can be made of scarce research resources.

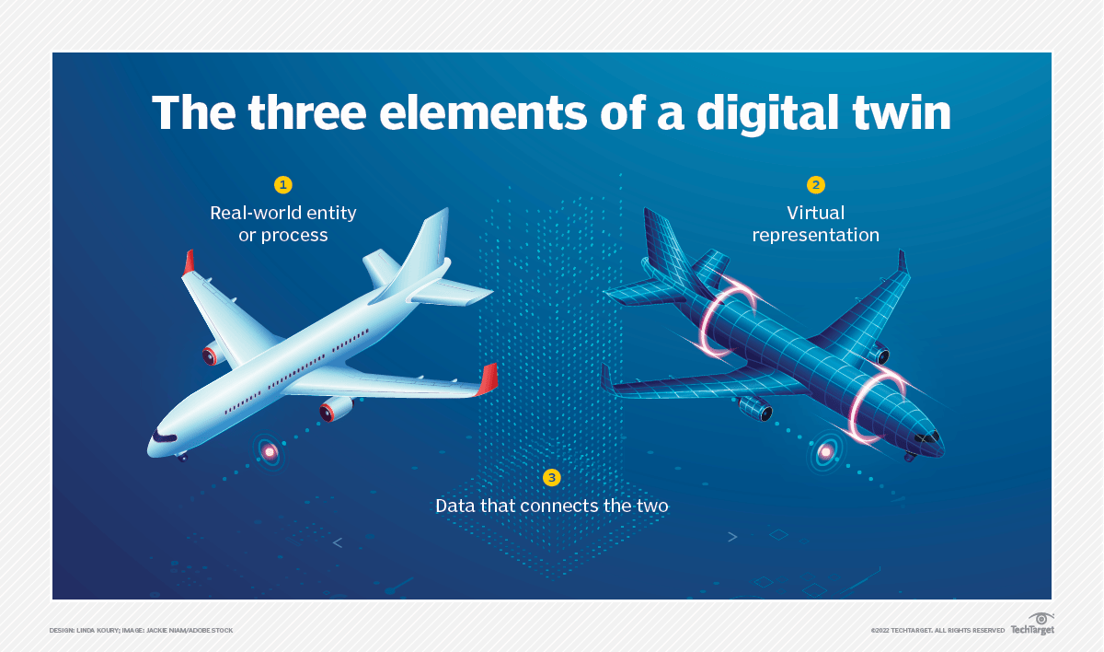

A digital twin is a simulation of the real world intended to support real-time decision making, IBM explains:

A digital twin is a virtual representation of an object or system designed to reflect a physical object accurately. It spans the object's lifecycle, is updated from real-time data and uses simulation, machine learning and reasoning to help make decisions.

IBM continues:

The studied object—for example, a wind turbine—is outfitted with various sensors related to vital areas of functionality. These sensors produce data about different aspects of the physical object’s performance, such as energy output, temperature, weather conditions and more. The processing system receives this information and actively applies it to the digital copy.

After being provided with the relevant data, the digital model can be utilized to conduct various simulations, analyze performance problems and create potential enhancements. The ultimate objective is to obtain valuable knowledge that can be used to improve the original physical entity.

The idea of digital twins has with time migrated from manufacturing and processes to biomedical sciences and social systems to reach the holistic vision of digital twins at the planetary scale.1 Offered to our imagination as a scientific basis for decision-making in the Anthropocene, digital twins of the earth plan to integrate Earth system simulations with satellites, drones, undersea cables, buoys, crop sensors and mobile phones.2

“Modellers have acquired a central position at the heart of the climate change discussion, and make use of this privileged state to increase their political standing and funding, putting themselves at the helm of the climate change narratives and making climate change itself into an all-encompassing meta-narrative”

The future is with us already in the utopian vision of the proponents of the aptly named DestinE, who see this project in the context of a great transformation:

[...] with the advent of the Digital Transformation, the interconnection between the physical and the digital world has become almost complete: economic, industrial, and social relationships have been moved to the “cyber-physical” world, where all the relevant stakeholders are included more easily and can intensively cooperate in generating the knowledge required for addressing a given purpose.3

Euronews, a Brussels-based magazine, announces “Scientists have built a “digital twin” of Earth to predict the future of climate change.” According to Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice-President for a “Europe Fit for the Digital Age,”

The launch of the initial Destination Earth (DestinE) is a true game changer in our fight against climate change … It means that we can observe environmental challenges which can help us predict future scenarios - like we have never done before... Today, the future is literally at our fingertips.

DestinE is one among a series of projects aimed to build digital twins of the planet.4 The idea that we can build a silicon-based replica the earth has a clear cultural appeal, a Promethean vision of humans’ ultimate escape from materiality.

For Nils Gilman,

The Earth … is an intricate web of ecosystems, with myriad layers of integration and interaction between various geophysical systems and living beings — both human and nonhuman — that must be understood as a totality. … A holistic understanding of planetary phenomena have been accelerated by new planetary-scale technologies of perception — a rapidly maturing and integrating megastructure of sensors, networks, and supercomputers that together are rendering various planetary systems more and more visible, comprehensible, and foreseeable. This recently evolved exoskeleton — in essence a distributed sensory organ and cognitive layer for the planet — is fostering fundamentally new forms of what Benjamin Bratton calls planetary sapience.

In the current ecosystem of science digital twins of the earth are currently unstoppable given their considerable appeal and the supporting advocacy. Few voices are found in the academic literature who contest the feasibility and the desirability of the project. Among those, some scholars from different disciplines, including myself, have recently argued that this faith in the capacity of mathematical models to describe the real says more about the marketing skill of their proponents than about the planet or its climate.

Models exist in a state of exception,5 having appropriated the academic prestige of mathematics and physics6 while at the same time escaping the critical gaze of philosophers and social scientists, including to some extent that of the sociologists of quantification.7 We reached this conclusion by comparing work on mathematical models with what sociologists say about quantification in statistics,8 economics,9 algorithms and artificial intelligence.10

According to our analysis, modellers have acquired a central position at the heart of the climate change discussion, and make use of this privileged state to increase their political standing and funding, putting themselves at the helm of the climate change narratives and making climate change itself into an all-encompassing meta-narrative, subsuming all ailments of humans and their planet, inclusive of wars, authoritarianism, migrations, and various forms of aggression to planetary ecosystems.11

The project of digital twins represents the pinnacle of this movement.

In our piece in WIRES Climate Change we critique the philosophical and epistemological foundations of the digital twin projects which are based on a reductionistic and Newtonian logic of Nature, contrary to relational ecology and system thinking. We advance doubts about the promised scientific advancements brought about by scaling mathematical models down to the scale of the kilometer:

The higher the resolution (i.e., the greater the localisation), the more non-physical feedbacks emerge as relevant, whether it be the micro-climatic effects of forest stands or the albedo micro-patterning of slush ponds on ice sheets. Scale change often brings about non-trivial shifts in complexity and governing principles, and finer-grained scales may reveal deterministically-driven chaotic behaviour.12 A different resolution may require different, perhaps yet unknown, process descriptions.

We conclude with a four-point recipe for a kinder future, based on developing several separate fit-for-purpose models rather than a model of everything, exploring the potential of simple, heuristic-based models in climate/environmental settings, collecting and integrating data from divergent and independent sources, including traditional knowledge, and abandoning a physics-centered vision of the planet in favour of,

… a naturally fluctuating and irreducibly uncertain diversity of relational processes, both social and biological, warranting more pluralist and provisional practices of care […] to contrast socioecological narratives of ecological modernization, green growth, ecosystem services and the like.

The recent epidemic of COVID-19 initially assigned unwarranted prestige to mathematical models to predict the evolution of the contagion,13 followed by a important critiques of model misuse or abuse.14 The modelling of COVID-19 motivated us to publish a volume entitled The Politics of Modelling(Oxford University Press), where we discuss strategies of model domination and possible avenues for model resistance.

Sociologist of science Brian Wynne notes in relation to large modelling projects:

Whether deliberately conceived and used in this way or not, big modeling can be interpreted as a political symbol whose central significance is the diseducation and disenfranchisement of people from the sphere of policymaking and responsibility, [p. 311]15

Wynne also suggests that,

Indeed, policy analysis, especially that conducted around large-scale modeling, tends to be structured in such a way that each modeling team is virtually its own peer group community, [p. 314]

Digital twins arise from a nexus16 of sociopolitical and technological changes where numbers — however they are generated and whether they are visible such as in statistical figures or invisible such as those running in the belly of algorithms17 — increasingly drive societal discourse.

We offer here three short theses about what we can learn from the digital twins’ project about the type of science and of society from which the project originates.

Numbers are seductive, and performative — they act on the reality they are supposed to just describe.18 Numbers confer epistemic power and legitimacy,19 and have become the prevalent means to express value in our societies.20 Access and production of numbers reflect and reinforce existing power structures.21 Numbers capture our attention by selectively orienting our attention. Numbers can become invisible as they penetrate every aspect of life via large models, algorithms and artificial intelligence. Numbers and facts have become synonyms. Numbers have colonized facts.

Fact signalling with numbers — “a practice where the stylistic tropes of logical thinking, scientific research, or data analysis is worn like a costume to bolster a sense of moral righteousness and certitude” — has become rampant and is practiced by experts, purported fact checkers, politicians and media. A similar craft is practiced by so-called ‘value entrepreneurs’22 — experts whose job is to measure social value of different measures for the purpose of establishing legitimacy, showing conformity, changing behaviour or justifying a field. Fact signaling is also practiced by corporate actors to defend their interests under the pretence of defending science from its purported enemies.23 Numbers have become a measure of virtue.

Media — co-responsible for 1 and 2 above — have failed to keep proper tabs on the experts, at times fostering bad science or outright deception at the hands of experts. In politics, media contribute to a futile campaign to defend democracy and the values of enlightenment by “checking the facts” (always with numbers). As noted by a cognitive linguist, this plays in the hands of undemocratic forces by multiplying their message. Unwise use of numbers pollutes democratic life.

As noted by biologists, investing resources into a digital quest for biodiversity detracts funds from a physical quest run in the ecosystems and in the countries where this quest could be advanced in more meaningful ways.24 Unlike the case of algorithms and artificial intelligence — where the alarm for societal harm is voiced by philosophers, jurists, economists, practitioners and sociologists of science — possible harms of mathematical models and their digital twins remain at the margins of our perception.25 We academics and practitioners who sit at the intersection of science and society need to change this culture.

As we concluded in our essay, a more human alternative is possible if we pay enough attention the challenge.

Read our full article:

Saltelli, A., Gigerenzer, G., Hulme, M., Katsikopoulos, K., Melsen, L. A., Glen, P., Pielke, J., Roger A., Robertson, S., Stirling, A., Tavoni, M., & Puy, A. (2024). Bring Digital Twins Back to Earth. WIRES Climate Change, e915. http://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.915.

Here at THB we are happy to share a diversity of perspectives on a diversity of topics. We welcome your comments, questions, critique. Thanks for your support — YOU make THB possible.

Editorial, ‘The increasing potential and challenges of digital twins’, Nat Comput Sci, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 145–146, Mar. 2024, doi: 10.1038/s43588-024-00617-4.

S. Nativi, P. Mazzetti, and M. Craglia, ‘Digital Ecosystems for Developing Digital Twins of the Earth: The Destination Earth Case’, Remote Sensing, vol. 13, no. 11, Art. no. 11, Jan. 2021, doi: 10.3390/rs13112119.

Ibid.

P. Bauer, B. Stevens, and W. Hazeleger, ‘A digital twin of Earth for the green transition’, Nat. Clim. Chang., vol. 11, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Feb. 2021, doi: 10.1038/s41558-021-00986-y; X. Li et al., ‘Big Data in Earth system science and progress towards a digital twin’, Nat Rev Earth Environ, pp. 1–14, May 2023, doi: 10.1038/s43017-023-00409-w; Y. Rao et al., ‘Developing Digital Twins for Earth Systems: Purpose, Requisites, and Benefits’, Jun. 19, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2306.11175. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2306.11175.

A. Saltelli, A. Puy, and M. Di Fiore, ‘Mathematical models: a state of exception’, International Review of Applied Economics, vol. June 11, 2024.

P. J. Davies and R. Hersh, Descartes’ Dream: The World According to Mathematics (Dover Science Books). London: Penguin Books, 1986. Accessed: Nov. 15, 2021.

A. Mennicken and W. N. Espeland, ‘What’s New with Numbers? Sociological Approaches to the Study of Quantification’, Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 223–245, 2019, doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041343.

A. Mennicken and R. Salais, ‘The New Politics of Numbers: An Introduction’, in The New Politics of Numbers. Utopia, Evidence and Democracy, Andrea Mennicken and Robert Salais., Palgrave Macmillan, 2022, pp. 1–44.

M. S. Morgan, The World in the Model: How Economists Work and Think, New edition. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

A. Saltelli and A. Puy, ‘What Can Mathematical Modelling Contribute to a Sociology of Quantification?’, Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, vol. 10, no. 213, 2023, doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4212453; M. Di Fiore, M. Kuc Czarnecka, S. Lo Piano, A. Puy, and A. Saltelli, ‘The Challenge of Quantification: An Interdisciplinary Reading’, Minerva, vol. 61, pp. 53–70, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s11024-022-09481-w.

M. Hulme, Climate Change isn’t Everything: Liberating Climate Politics from Alarmism, 1st edition. Medford: Polity, 2023.

A. Stirling, ‘From Controlling Global Mean Temperature to Caring for a Flourishing Climate’, in Climate, Science and Society: A Primer, Z. Baker, T. Law, M. Vardy, and S. Zehr, Eds., London: Routledge, 2024, pp. 303–312. doi: 10.4324/9781003409748.

Rhodes and K. Lancaster, ‘Mathematical models as public troubles in COVID-19 infection control: following the numbers’, Health Sociology Review, pp. 1–18, May 2020, doi: 10.1080/14461242.2020.1764376.

A. Saltelli et al., ‘Five ways to make models serve society: a manifesto - Supplementary online material’, Nature, vol. 582, 2020; A. Saltelli and M. Di Fiore, Eds., The politics of modelling. Numbers between science and policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023.

B. Wynne, ‘The institutional context of science, models, and policy: The IIASA energy study’, Policy Sci, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 277–320, Sep. 1984, doi: 10.1007/BF00138709.

A. Saltelli and P.-M. Boulanger, ‘Technoscience, policy and the new media. Nexus or vortex?’, Futures, vol. 115, p. 102491, Nov. 2019.

E. Popp Berman and D. Hirschman, ‘The Sociology of Quantification: Where Are We Now?’, Contemporary Sociology, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 257–266, 2018.

E. S. Merry, The Seductions of Quantification: Measuring Human Rights, Gender Violence, and Sex Trafficking. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

T. M. Porter, Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life. Princeton University Press, 1995.

A. Saltelli et al., ‘Why ethics of quantification is needed now. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose’, UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, London, WP 2021/05, 2021.

I. Bruno, E. Didier, and T. Vitale, ‘Editorial: Statactivism: forms of action between disclosure and affirmation’, The Open Journal of Sociopolitical Studies, vol. 2, no. 7, pp. 198–220, 2014, doi: 10.1285/i20356609v7i2p198.

E. Barman, Caring Capitalism: The Meaning and Measure of Social Value. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316104590.

S. Foucart, S. Horel, and S. Laurens, Les gardiens de la raison. Enquête sur la désinformation scientifique. Éditions La Découverte, 2020; A. Saltelli, D. J. Dankel, M. Di Fiore, N. Holland, and M. Pigeon, ‘Science, the endless frontier of regulatory capture’, Futures, vol. 135, no. 102860, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2021.102860.

M. Westerlaken, ‘Digital twins and the digital logics of biodiversity’, Soc Stud Sci, p. 03063127241236809, Mar. 2024, doi: 10.1177/03063127241236809.

B.-C. Han, Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power. London ; New York, 2017; A. Supiot, Governance by Numbers: The Making of a Legal Model of Allegiance. Hart Publishing, 2017; S. Zuboff, The age of surveillance capitalism : the fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs, 2019; C. O’Neil, Weapons of math destruction : how big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Random House Publishing Group, 2016; D. McQuillan, Resisting AI: An Anti-fascist Approach to Artificial Intelligence. Bristol University Press, 2022. Accessed: Nov. 26, 2023.

I am a practicing Aerospace Systems Engineer (for many years). I know a bit about digital modeling - for design description, modeling physics and other behavioral phenomena, etc. These are useful for engineering.

However, in science, the purpose of a behavioral model is to provide a mathematical representation of the theory you are hypothesis testing, so that you can compare your hypothesis with actual data to determine if your hypothesis needs to be rejected or not rejected.

To this point, the CMIP models, when run with past boundary conditions and initial conditions, diverge greatly from the actual historic data, which tells us the "Climate Science" is rather crude, and that Climate Models are dangerous for making future predictions. This is true because 2 of the most important factors in climate are absent from current models.

This is well documented by Lindzen and Happer, but the Climate fanatics won't talk about it.

I am opposed to wasting any more money and/or resources on climate modeling except as pertains to hypothesis testing. We should put that money into something that is actually useful, and not a Welfare-for-Climate-Scientists program.

It takes a chest full of hubris to move from "All models are wrong. Some are useful" and "Climate is a non-linear chaotic system. Therefore long-term predictions of climate are not possible." to the idea of a digital twin of earth. To even attempt it assumes that all relevant physical relationships are already completely understood. Never mind about the failure of the models to predict this year's hurricanes. Never mind about the inability of the models to deal with clouds. Wow. I am awed by the arrogance of the modelers.