Catastrophes of the 21st Century

We focus too much on the familiar and risk being unprepared for inevitable catastrophe

The recent Marshall Fire here in my community and the Hunga Tonga volcanic eruption this week have me thinking about (what for many are) unexpected disasters, but which really should not be. In 2015 I was invited to Australia’s Gold Coast to give a lecture at the biennial Aon Benfield Australia Hazards Conference. I used the opportunity to write a paper looking into the future, and specifically how well prepared the world may be for catastrophes of the 21st century. In the paper I argue that our attention may be overly focused on familiar hazards and under-focused on others.

There are few ways to better display our ignorance than by speculating on the long-term future. At the same time, making wise decisions depends upon both anticipating an uncertain future and the limits of what we can know. I propose a three-part taxonomy for thinking about future disasters:

The familiar — hazards that we have come to expect based on experience and knowledge, such as hurricanes, earthquakes and tornadoes.

The emergent — hazards that are the product of a complex, interconnected world, such as financial meltdowns, supply chain disruption and pandemics.

The extraordinary — hazards that may or may not be foreseen or foreseeable, but for which we are wholly unprepared, such as an asteroid impact, massive solar storm, or even fantastic scenarios found only in fiction, such as the

consequences of contact with alien life.

We spend most of our time thinking, studying and preparing for the familiar, and with good reason as they are familiar because these events happen frequently. That attention has paid off. As I frequently note, trends in the human impacts of familiar extreme weather and geophysical events have been moving in the right direction for over a century and we know what we need to do to continue to reduce vulnerabilities to disaster.

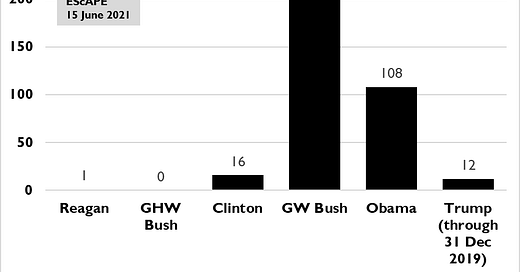

However, our attention on the familiar has been accompanied by less attention on the emergent and the extraordinary. Consider the data above, which shows considerable attention paid to pandemics under the George W. Bush Administration in the face of the H1N1 epidemic, but much less before or since (you can check out similar trends in Congress, government advisory committees and in reports of the National Academy of Sciences). A lack of attention to pandemic planning is one reason why the U.S. found itself unprepared in important respects for the COVD-19 pandemic.

The lack of attention to pandemics by U.S. presidents on the eve of the biggest may also reflect a lack of attention to researching pandemics and pandemic preparation by us academics. In 2013 Nick Bostrom lamented of issues of truly existential risk, “it is striking how little academic attention these issues have received compared to other topics.” For my 2015 talk I collected data from that year on the number of published papers on the familiar topic of climate change and compared that to four emergent and extraordinary risks: asteroid impact, global pandemic, super volcano and the discovery of extraterrestrial life. That data is shown in the figure below.

Climate change is important to be sure, but in 2015 was it really deserving of 18 times the number of papers than did research on global pandemic? In 2021 this ratio flipped around — for obvious reasons — with 3 times the number of articles on pandemic as compared to “climate change.” But there can be no doubt that there is much knowledge we are gaining during the pandemic that would have been useful to have available when it started. Should the scientific community do a better job in prioritizing research on topics that are not currently popular among researchers and funders but may be much more important in the future? Are research incentives (like funding and publication) geared toward supporting such work?

I end my paper with three hypotheses, to stimulate discussion and debate:

The challenge of ordinary catastrophes is not generally one of knowledge creation, but knowledge application.

Earthquakes, tropical cyclones and the like are well-known phenomena. The actions that serve to foster safety and manage economic losses are also well known. In general, the challenge with respect to these types of events is to apply that which is known and shown to be successful. In the United States in 2005 Hurricane Katrina resulted in more than 1,000 deaths and $80 billion in losses despite hitting a vulnerable region prone to extreme hurricanes in a wealthy nation with ample experience with such storms. Just because we know how to reduce vulnerability doesn’t mean we always succeed. Overall, disaster costs worldwide have increased but at a rate slower than the overall accumulation of global wealth. Even under aggressive scenarios of climate change (such as proposed by the IPCC) a diminishing role for disaster losses (including earthquakes) might be expected. However, there is no guarantee of such outcomes and constant attention to disaster risk reduction will be necessary to secure the continuation of the positive trends in disaster losses observed over recent decades.

The challenge of emergent phenomena requires the application of mitigation strategies quite different than those typically used on the context of ordinary disasters.

Emergent phenomena, by definition, are generally unpredictable. Thus, strategies to prepare for catastrophes that emerge for interacting components of a system are likely to miss what matters. Research utilizing methods of simulation, scenario planning, robust decision making, and resilient systems are key to developing an ability to effectively reduce the risks of emergent systems and to deal with crises as they emerge. Methods more focused on prediction or projection of futures are likely to miss many emergent phenomena, by definition.

The response to the threat of Ebola in 2014 provides one example of a successful response to an emergent phenomenon. The combination of a terrifying, deadly disease and globalize travel networks meant that Ebola presented risks that appeared around the world, far from the actual location of the disease outbreak. The risks were not just medical but also social, as the disease created a considerable amount of fear, some justified by medical science, but much of it not. The World Health Organization observed “What began as a health crisis snowballed into a humanitarian, social, economic and security crisis. In a world of radically increased interdependence, the consequences were felt globally.”

Dealing with Ebola, like SARS before it, was likely facilitated by the fact that the disease did not spread easily — we didn’t get so fortunate with COVID-19. David Morens, an infectious disease specialist at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland warned presciently in 2015 that familiar diseases were third on our list of worries: “second on the list is the one we haven't thought of, and at the very top is the one we can't imagine.” Dealing with emerging threats requires developing strategies to deal with risks that we aren’t thinking of and even those that we may not even be able to imagine.

The challenge of extraordinary catastrophes requires more attention to that which is largely outside our discussions of risk.

Consider that in 1960 the world had yet to gain awareness of the threats of chlorofluorocarbons to the ozone layer, the existence of AIDS or Ebola, and nanotechnology, genetic modification, gain-of-function experiments and artificial intelligence had yet to be created, except perhaps in science fiction. Tomorrow’s threats are unknown and perhaps unknowable. However, this need not stand in the way of a more expansive expert discussion about our collective ability to deal with possible futures.

Some scenarios of undesirable futures are certainly imaginable even if the details are not — such as a global pandemic, an asteroid impact or nuclear war (whether inter-state or via terrorism). Expanding our discussions about how we might deal with such unlikely but possible catastrophes may ultimately help us to develop options for dealing with those threats which we are not presently imagining as possible or focusing much attention on. Organizations such as the Global Challenges Foundation have helpfully initiated such conversations.

Ultimately, the one aspect of future catastrophes that experts may have the most ability to influence is the “marketplace of ideas.” We may not be able to predict the future or to ensure that decision makers well use available information. However, we have no excuse for not conducting research that might be helpful in supporting those decision makers in preparing for an uncertain future. That means expanding the scope of our view and correcting inefficiencies in the “marketplace of ideas” wherever we find them.

You can read my full paper here.

Paying subscribers to The Honest Broker receive subscriber-only posts, regular pointers to recommended readings, occasional direct emails with PDFs of my books and paywalled writings and the opportunity to participate in conversations on the site. I am also looking for additional ways to add value to those who see fit to support my work.

There are three subscription models:

1. The annual subscription: $80 annually

2. The standard monthly subscription: $8 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

3. Founders club: $500 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who have the ability or interest to support my work at a higher level.

Politicians do not act; they pose. cit. G.K. Chesterton