What the media won't tell you about ... Wildfires

What the IPCC really says, trend data and the complexities of adaptation

Wildfire, common to many healthy ecosystems, is a particularly challenging problem for society because of its impacts on property and health. It is also challenging because people like to locate themselves in fire-prone places and do things that ignite fires. We have learned through hard experience that complete suppression of wildfire is not the best policy — despite what Smokey Bear says — as it can actually lead to even greater and more harmful wildfire events. These dynamics together make wildfire a challenging issue for policy.

This week, wildfire smoke from fires in Canada have drifted south along the eastern seaboard of the United States, affecting New York City and Washington, DC, and correspondingly capturing a lot of media attention. The event should offer a teachable moment on the complexities of climate and the challenges of adapting to a volatile world.

With this post I discuss some of the aspects of wildfires that I see as missing in the public discussion. I start with what the Intergovernmental panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says about wildfire, discuss readily available data on wildfire trends and conclude with the complexities of policy in the face of interconnected human-environment dynamics.

The IPCC has not detected or attributed fire occurrence or area burned to human-caused climate change

The IPCC is of course not infallible, but it is essential and always a good first place to start when discussing what is known about extreme events and their impacts. Many people are surprised when they learn that the IPCC does not evaluate trends in or causes of wildfires.

Instead, the IPCC focuses on “fire weather” which it defines as (emphasis in original):

“Weather conditions conducive to triggering and sustaining wildfires, usually based on a set of indicators and combinations of indicators including temperature, soil moisture, humidity and wind. Fire weather does not include the presence or absence of fuel load. Note: distinct from wildfire occurrence and area burned.”

For a wildfire to occur requires more than just “fire weather” — it also requires fuel and a source of ignition. In fact, according to the IPCC, the weather is not the most important factor in fire: “human activities have become the dominant driver.” Indeed, most wildfires are started by human activity.

The IPCC expresses “medium confidence” (about 50-50) that in some regions there are positive trends in conditions of “fire weather”:

"There is medium confidence that weather conditions that promote wildfires (fire weather) have become more probable in southern Europe, northern Eurasia, the USA, and Australia over the last century"

By 2050, the IPCC expects with “high confidence” (about 8/10) that fire weather will increase in only a few regions, noted by the red circles in the IPCC figure that I annotated below.

The IPCC also identifies when it expects that the “emergence” of a signal of climate change will be detectable for various impact “climate impact drivers.” I have reproduced that table below, with “fire weather” highlighted in blue. Most people will likely be surprised by the amount of white cells in the table — indicating a lack of signal emergence, even out to 2100 and under our old friend RCP8.5. For “fire weather” a signal does not emerge through 2100.

Close followers of the IPCC (and my writings on its recent reports) may notice that some of the entries in the table above don’t seem to line up with claims of detection and attribution made elsewhere in the IPCC AR6 — I would agree. But that is an issue for the IPCC.

In short, the IPCC does not provide a basis for strong claims of detection or attribution of “fire weather” to climate change. The IPCC is silent on trends in fire numbers and area burned. These conclusions are contrary to almost all media reporting.

Let’s next look at some data.

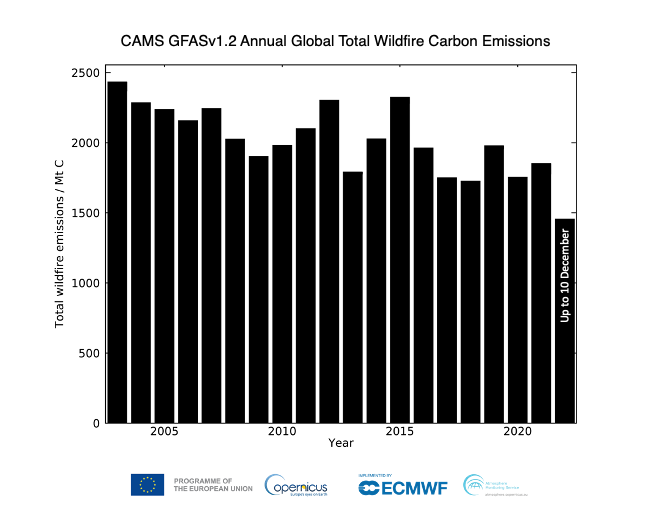

Globally, emissions from wildfires has decreased globally over recent decades, as well as in many regions

The figure above shows that wildfire emissions have declined globally since 2003, based on data from the EU. That doesn’t mean that wildfires have decreased everywhere. For instance, wildfires have increased over recent decades in the Western United States, France and Russia. It does mean that claims that wildfire has increased globally in recent decades do not have empirical support, at least by this important and widely accepted metric.

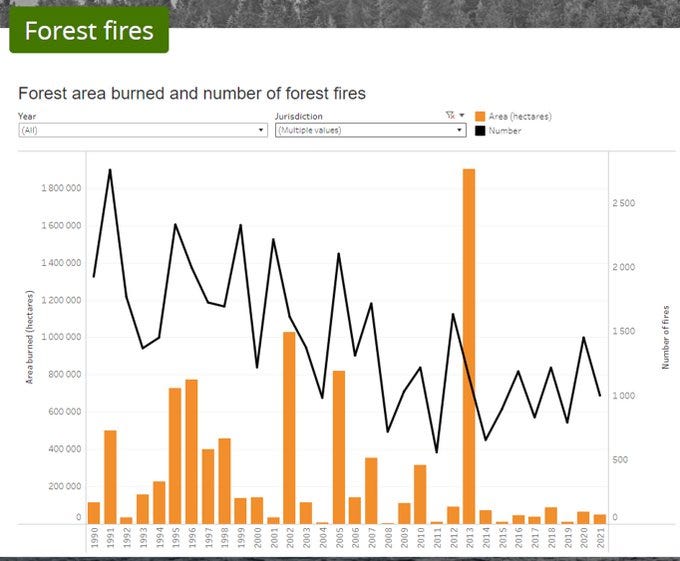

Canada — the focus of extensive fire activity this week polluting the air in the eastern U.S. and elsewhere — has not seen an increase in fire activity in recent decades, as you can see in the figure below, showing official data.

In Quebec specifically, there is also no indication of a long-term increase in fire activity, as you can see below. In fact, recent years have been unusually quiet.

Looking at data from the NFDP, we can see that the majority of fires in Quebec and the area that they burn over the past decade are caused by humans, with the balance caused by lightning, as shown in the figure below.

Over the much longer term, going back to 1700, research indicates that recent “burn rates” across Canada in recent decades have been much lower than in centuries past, as you can see in the figure below.

That is a lot of data, I know. What you should take from it is the following:

Wildfire globally has decreased in recent decades;

Still, some regions have seen increases;

Neither Canada nor Quebec have seen increases this century;

Fire incidence across Canada is lower today than in centuries past.

Wildfires are a natural part of ecosystems, are related to climate change and a problem for society

Established above is the fact that climate change is expected to affect the environment in which wildfires occur, specifically through enhanced “fire weather” conditions in some locations. While the IPCC has only medium confidence at present and an expectation that the clear emergence of a signal may take decades, let’s just postulate that climate change has an effect.

OK, now what?

According to one prominent climate scientist, there is only one way that we can manage wildfires, and that is with changes to global energy policy:

The only way to prevent these events from becoming more frequent and more intense is to prevent the continued warming of the planet. And the only way to do that is to decarbonize our economy as rapidly as possible.

That of course is wrong. There are very good reasons to decarbonize the global economy, but doing so to control wildfires and their impacts is not among them.

Fortunately, there are many things that can be done to address wildfire risk and the associated impacts. The OECD has published an excellent report that discusses many of these prevention measures, which are summarized in the figure below.

Given the complexities of the human-environment interconnections related to wildfire, the straightforward detection and attribution framework of the IPCC may not be appropriate or particularly useful. If wildfire is to be more than a climate advocacy talking point, we must take serious the many complexities in their local contexts.

For instance, just today here in Colorado we learned that the Marshall Fire, which consumed more than 1,000 homes just outside Boulder in December 2021, was ignited by a combination of open burning and an arcing power line.

But the disaster was caused by a combination of a wind storm, managed open space with invasive species, a rainfall deficit, decades of land use decisions that placed neighborhoods alongside combustible lands, homes build of flammable materials and more. Sure, say that climate change played a role if that suits, but after that is said, a far more important discussion has to happen about development, building codes. land use and management, open space, prescribed burns and so on.

Wildfires are important in many parts of the world. They will become more important as people continue to develop in fire prone locations and if “fire weather” conditions expand. A first step in better management of wildfire-prone regions is to understand their complexities, and that means not reducing everything to climate with global energy policy as the only solution.

Thanks for reading! Please click that little heart at the top, and then the “restack” button. Comments and shares are always welcomed.

Excellent, as always.

I'm puzzled by the idea that an increase in global temperature of a fraction of a degree to a degree could cause any noticeable increase in fires. Is it not the case that most of the warming is at night and at the poles? And how can such a small increase have any significant effect on combustibility? Can such a small, gradual change really cause enough drying? I'm not saying it's impossible, just that it seems highly implausible.

Great piece Roger.

Thanks for data, it’s all we’ve got with the climate/insane.

First, pet peeve as I live in Alberta.

Fires started by humans are not wild fires, they are “fires”.

We had a hotter than average May after a cold crappy winter and everyone rushed out to the countryside to take advantage and boom, fires everywhere within 2 days and no way to fight them as just too many all at once.

Stop starting fires and this would just be the nicest May in a decade.

That’s the entire story. 95% human caused.

Peeve 2.

I’m in Vienna this week and the only English Channel I get is Skynews which seems to be trying to overtake the BBC in hairbrained hair on fire climate alarmism for Britain. They are playing a loop about the smoke in NYC talking about how it started in the west of canada “then spread to eastern canada”, as though the whole country is on fire, buttressing it with a continental smoke map that basically shows the position of the jet stream which also explains why it’s hot and dry where it is.

It’s very misleading and if I was like most people instead of being someone who “reads” and “thinks” it would be very easy to fall for it.

Don’t even get me going on their other loop today about sea ice, just wrong wrong wrong.

Infuriating.