Last week, I testified before the Senate Committee on the Budget in a hearing titled, Droughts, Dollars, and Decisions: Water Scarcity in a Changing Climate.1 The hearing was the 18th in the Committee’s series on climate change this Congress, prompting the Wall Street Journal to suggest “the old-fashioned idea that the Budget Committee ought to focus on the budget.”

The hearing could easily have been held the Senate Agriculture Committee, and indeed, almost all the questions from senators to the witnesses came from Budget Committee members who are also on the Agriculture Committee.

I was invited to testify on what the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) says about drought — and I focused my testimony on the finding of the IPCC Sixth Assessment (AR6) Working Group 1 (WG1). I always appreciate the opportunity to testify before Congress, and I thank Senators Whitehouse and Grassley for the opportunity.2

Aside from my testimony, there was essentially no discussion of climate change — it was mostly about local farming and urban water management, both crucially important. All the witnesses were excellent, and the Senators asked some worthwhile questions.

Some tidbits I left with from the other witnesses:

Despite a large increase in population, Southern California has cut its water consumption by about half since the 1970s.

Almost all of the world’s carrot seeds are produced in the high desert of Oregon.

Despite variability and changes in U.S. climate, agricultural productivity has continued to increase, and with no end in sight.

My testimony focused on summarizing what the IPCC AR6 Working Group 1 said about drought, with a focus on the United States (specifically, North America).

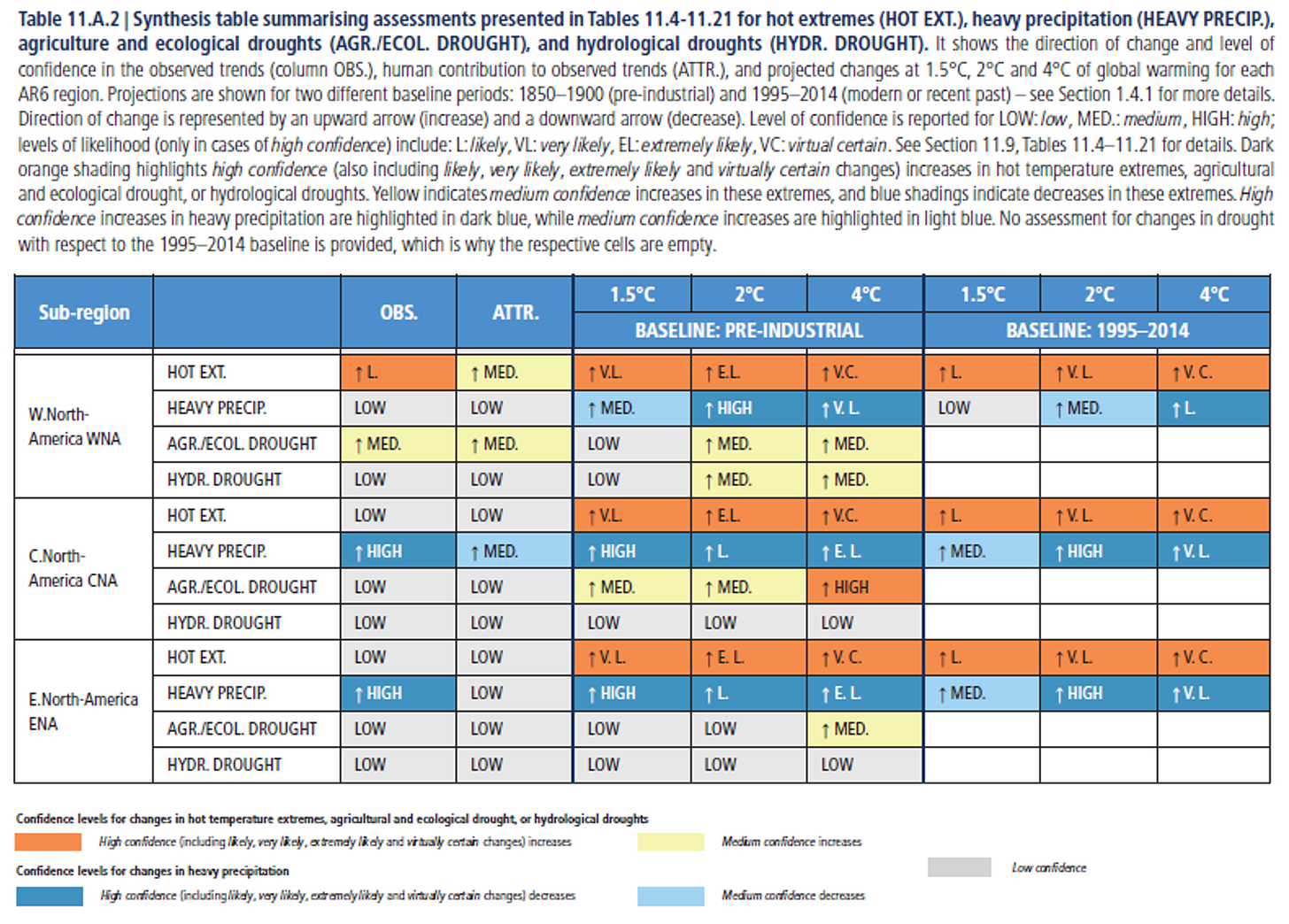

The image above, a screenshot from the IPCC AR6, is worth looking at closely. It shows:

Low confidence (2 in 10) in detection of changes in drought across the U.S., with the exception of increasing “agricultural and economical drought” in Western North America at medium confidence (5 in 10).

No ability to express any confidence in how drought may change from a 1995 to 2014 baseline under future temperature changes of >1.5C from that baseline (Note: a 1.5C change from that recent baseline is about the same as a 2.5C change from preindustrial, which is similar to a “current policies” baseline and well below a SSP2-4.5 scenario).3

In fact, the IPCC has not achieved detection of trends in drought anywhere in the world at a level consistent with the IPCC’s threshold for detection (i.e., at least very high confidence or 9 in 10). The IPCC has detected an increase in hydrological drought in the Mediterranean and North East South America with high confidence (8 in 10) but has, respectively, only medium confidence and low confidence in attribution in those two regions (5 in 10 and 2 in 10).

The IPCC does conclude with high confidence that human-caused climate change affects the hydrological cycle, and thus drought. However, achieving detection and attribution of trends in the IPCC’s various definitions of drought — both observed and projected — in the context of significant internal variability remains a challenge.

Don’t take it from me. Here is what the IPCC AR6 concluded:

There is low confidence in the emergence of drought frequency in observations, for any type of drought, in all regions. Even though significant drought trends are observed in several regions with at least medium confidence (Sections 11.6 and 12.4), agricultural and ecological drought indices have interannual variability that dominates trends, as can be seen from their time series (medium confidence)

In fact, published studies are lacking that explore when signals of projected changes in drought might emerge from the background of internal climate variability, under the IPCC’s framework for detection and attribution:

Studies of the emergence of drought with systematic comparisons between trends and variability of indices are lacking, precluding a comprehensive assessment of future drought emergence.

Given the closing “jaws of the snake” due to the growing recognition of the implausibility of extreme climate scenarios, it will be interesting to see what future “time of emergence” studies say about projected changes in drought. I’ll have a post dedicated to this neglected topic in the coming weeks.

As I said at the hearing, it is easy to perform anecdotal attribution of any weather and climate event that happens anywhere on the planet (Turbulence! Home runs! Migraines!). The IPCC tells us that reality is just a bit more complicated.

Climate change is real and important, of course, but reducing the causality of everything to climate change flattens our understandings and distracts from more detailed explorations of the proximate cause of events, which are always far more important for thinking through policy alternatives.

My oral remarks are reproduced below and you can find my full written testimony here in PDF. A full video of the hearing can be found here. In the coming weeks, I’ll have a post dedicated to my written testimony.

Prepared Remarks of Roger Pielke Jr. — 22 May 2024, Senate Budget Committee

Chairman Whitehouse and Senator Grassley

Thank you for the opportunity to testify today.

For almost 30 years, along with many colleagues, I have studied extreme weather and climate and associated impacts. Our work has been cited in the most recent assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC.

The IPCC is comprised of hard-working and intelligent people who reflect a spirit of public service. They are also humans, and the IPCC is of course fallible. Conclusions of IPCC reports are snapshots in time reflecting the evolution of scientific understandings. Individual experts of course may have legitimate views that are at odds with the IPCC, and that is of course expected in a diverse scientific landscape.

The IPCC Working Group 1 assessments of the literature on extreme events in my areas of expertise have, with few exceptions, done an overall excellent job accurately reflecting the scientific literature.

Today, I summarize what the most recent IPCC report concluded about the detection and attribution of trends in drought at the global scale and also for the United States.

I start with some key IPCC terminology:

DETECTION: “the process of demonstrating that climate or a system affected by climate has changed in some defined statistical sense, without providing a reason for that change. An identified change is detected in observations if its likelihood of occurrence by chance due to internal variability alone is determined to be small”

ATTRIBUTION: “the process of evaluating the relative contributions of multiple causal factors to a change or event with an assessment of confidence.”

DROUGHT: “periods of time with substantially below-average moisture conditions, usually covering large areas, during which limitations in water availability result in negative impacts for various components of natural systems and economic sectors”

It is more challenging to achieve detection and attribution of trends in drought than, say, hurricanes or tornadoes, because drought can be defined and measured in many ways in the context of significant natural climate variability. Detecting and attributing trends in drought impacts is even more challenging.

It is easy to identify drought trends over various time periods in various places that are the result of internal variability rather than indicative of a change in climate. Often, detection and attribution are confused, and so too is climate variability with climate change.

The IPCC finds with high confidence (i.e., an 8 in 10 chance) that human-caused climate change influences the global hydrological cycle and thus drought.

My written testimony makes four main points.

1. The IPCC focuses on three types of drought: meteorological, hydrological, and soil moisture deficits (which the IPCC calls agricultural/ecological drought).

2. At the global scale, the IPCC has not detected and attributed trends in any of the three types of drought for any region with high confidence (i.e., an 8 in 10 chance). For the United States, the IPCC has only low confidence (i.e., 2 in 10 chance) in detected or attributed trends in all three types of drought for all regions, except Western North America where it has medium confidence (i.e., 5 in 10 chance) in the detection and attribution of trends in agricultural/ecological drought.

3. Looking to 2100, at the global scale the IPCC does not expect that a signal of trends in drought will emerge in any region with high confidence (i.e., 8 in 10 chance). For the United States, the IPCC has only low confidence (i.e., 2 in 10 chance) that a signal of trends in drought will emerge from the background of natural variability in all three types of drought for all regions, except Western and Central North America for agricultural/ecological drought and also hydrological drought in Western North America – both at medium confidence (i.e., 5 in 10 chance).

I know that is a lot of words, but my written testimony includes several summary tables and figures from the IPCC reports that concisely summarize these IPCC findings and confidence levels.

In plain English, the IPCC concludes that changes to the climate system resulting from human activity, notably the emission of carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels, changes the hydrological cycle and thus affects drought. At the same time, the IPCC does not have high confidence that research has detected the signal of a change in past drought at the global scale or in the United States. Nor does the IPCC expect with high confidence such a signal to emerge beyond internal variability, even under its most extreme scenario, to 2100.

Such uncertainties and areas of ignorance can inform both mitigation and adaptation policies and planning.

4. To be clear, I emphasize explicitly and unequivocally that human-caused climate change poses significant risks to society and the environment, and that various policy responses in the form of mitigation and adaptation are necessary and make good sense.

Thank you and I welcome your questions.

❤️Click the heart to help THB get seen more widely on Substack!

Thanks for reading! I welcome your comments, questions, critique.

I was invited by Republicans. In the past I was invited by Democrats. I’ve always been a registered Independent in the state of Colorado .Read more here.

The IPCC’s two baselines — preindustrial and recent — has me thinking about practically relevant detection and attribution. Expect a post on this soon!

To be clear, I emphasize explicitly and unequivocally that human-caused climate change poses significant risks to society and the environment, and that various policy responses in the form of mitigation and adaptation are necessary and make good sense.

You usually include a proviso such as this in any of your climate-related posts, but with all due respect, I wish you add at the very least, “but these risks should not be feared.” It is fear that drives some of the alarmists; others, it is the desire for power and control. (See Bryce's latest post, "Environmentalism is dead."

Mankind has been adapting to climate change throughout his existence, and will adapt to any changes the future might bring. What will reduce the risks is a better understanding of what they are and how we can adapt as change unfolds. Policies that are aimed at adaption will have a far greater chance of success. Policies that are aimed at “stopping” will fail, inevitably and assuredly. I think we can agree on that?

All of that venting aside, this is a good post, as usual, and I thank you. You concluded that the IPCC does not expect with high confidence such a signal to emerge beyond internal variability. Given the decarbonization efforts now on-going, do you expect a signal to ever emerge?

I assume that the drivers for having the committee meet and take expert testimony on drought are claims that human caused climate change is causing droughts to become more severe and result in increased damage and loss. You do a yeoman’s job of showing that such claims are not supported by the work of the IPCC and that it is unlikely that any such claims will be supportable by 2100.

However you lose me with your point 4. Point 4 seems to say that in spite of the fact that droughts don’t seem to be worsening due to human caused climate change you remain convinced of the need to be deeply concerned about the adverse effects of climate change and the need to mitigate its effects. I submit that this is your opinion (shared by many but far from all experts) and shouldn’t be conflated with your factual discussion of trends in droughts.

Frankly I am struggling with understanding what it is that you are suggesting the committee members do.