What should the "average CEO" do on ESG related to carbon emissions?

Four tips for making a real difference

The title of this post is a question sent in by a reader from the world of finance and investment. He wants to know if and how businesses can make a difference when it comes to helping the world accelerate the decarbonization of the economy via the application of ESG principles and methods in their business operations. Summarized at the end of this post I’ll four suggestions to CEOs for how to get the most out of ESG while avoiding the pitfalls of playing “the game.”

Let me start with a warning. Much of what passes for ESG related to climate and carbon is just hot air. At its worst climate-related ESG can be a bunch of busy work that lines the pockets of the burgeoning ESG industry while subtracting from shareholder value. At its best climate related ESG offers a chance for businesses to align their operations with a widely-shared global policy goal (net-zero carbon emissions) while adding to shareholder value.

The challenge, of course, is how to tell the difference between busy work and making a real difference. That is what this post is focused on.

The first step in understanding how to make a difference is to understand — really understand — what it means to make a difference. The global energy economy is ridiculously complex. It is also much bigger than most people imagine. Look around you. More than 80% of the energy services that we enjoy globally comes from the burning of fossil fuels. At the same time there are billions of people around the world who do not even come close to the level of access to energy services that I and most readers of this post enjoy every day. In my introductory energy policy class students head routinely (and figuratively) explode when they get an appreciation of the scale of global energy use, along with their own personal consumption.

Carbon dioxide isn’t the only reason for climate change, but is the major one according to the IPCC and thus is the focus of this post. Achieving net-zero carbon dioxide means eliminating the burning of fossil fuels (unless we capture and store emitted carbon dioxide). We employ fossil fuels for lots of things beyond burning them for energy — like food production, industrial chemicals, plastics and more. Here, following the lead of The Economist, I’ll just focus on carbon dioxide emitted from the burning of fossil fuels.

Thanks to the easily-understood-yet incredibly-powerful Kaya Identity, we know that our toolbox for reducing and ultimately eliminating fossil fuel combustion has four options. That is it. There is no other option beyond these (to learn more please read The Climate Fix). They are, all else equal:

Reduce population

Reduce per capita GDP

Improve the energy intensity of economic activity (technically, energy/GDP)

Reduce the carbon intensity of energy (technically, CO2/energy)

That’s it. Those are the options for reducing carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels. The figure below, posted on Twitter today by Glen Peters (@Peters_Glen) of CICERO in Oslo, shows trends in the four Kaya factors over recent decades. You can see that population and per capita wealth are up (except in the case of the latter during the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic). You can also see that energy intensity is steadily downward, while carbon intensity just started declining about a decade ago (highlighted in Glen’s oval). To hit net-zero targets in the second have of this century will require that carbon intensity goes down much faster — and that means expanding carbon-free energy supply while eliminating the consumption of coal, natural gas and oil that emits uncaptured carbon dioxide.

When it comes to tools in the ESG toolbox, we can make things even more simple. No company is going to seek to reduce population — well, except maybe the tobacco industry. Similarly, no company is going to seek to reduce individual wealth. In fact, the entire reason that businesses exist is to increase profits which in turn increase GDP, most directly by providing goods and services that create or meet a market demand, thereby increasing individual and overall societal wealth. So we can take population and wealth off the table right away as levers that might be used to reduce emissions.

That leaves only two options: Improve energy intensity and reduce carbon intensity. Let’s take each in turn.

Improving energy intensity can occur in basically two ways. First, we can become more efficient in how we use energy. That means getting the same or better outputs from less energy consumption. We typically call this energy efficiency. Energy efficiency is a great thing, because it means that companies are paying less for an important input (energy) while still maintaining or even increasing outputs. A second way to reduce the energy intensity of the economy is to expand the share of less carbon-intensive economic activities, and decrease the share of more carbon-intense activities.

The current global energy crisis has put a bright spotlight on energy costs and supply. Any company that is not already looking to improve efficiencies is doing a disservice to its share holders. I am sure every CEO knows this far better than I do!

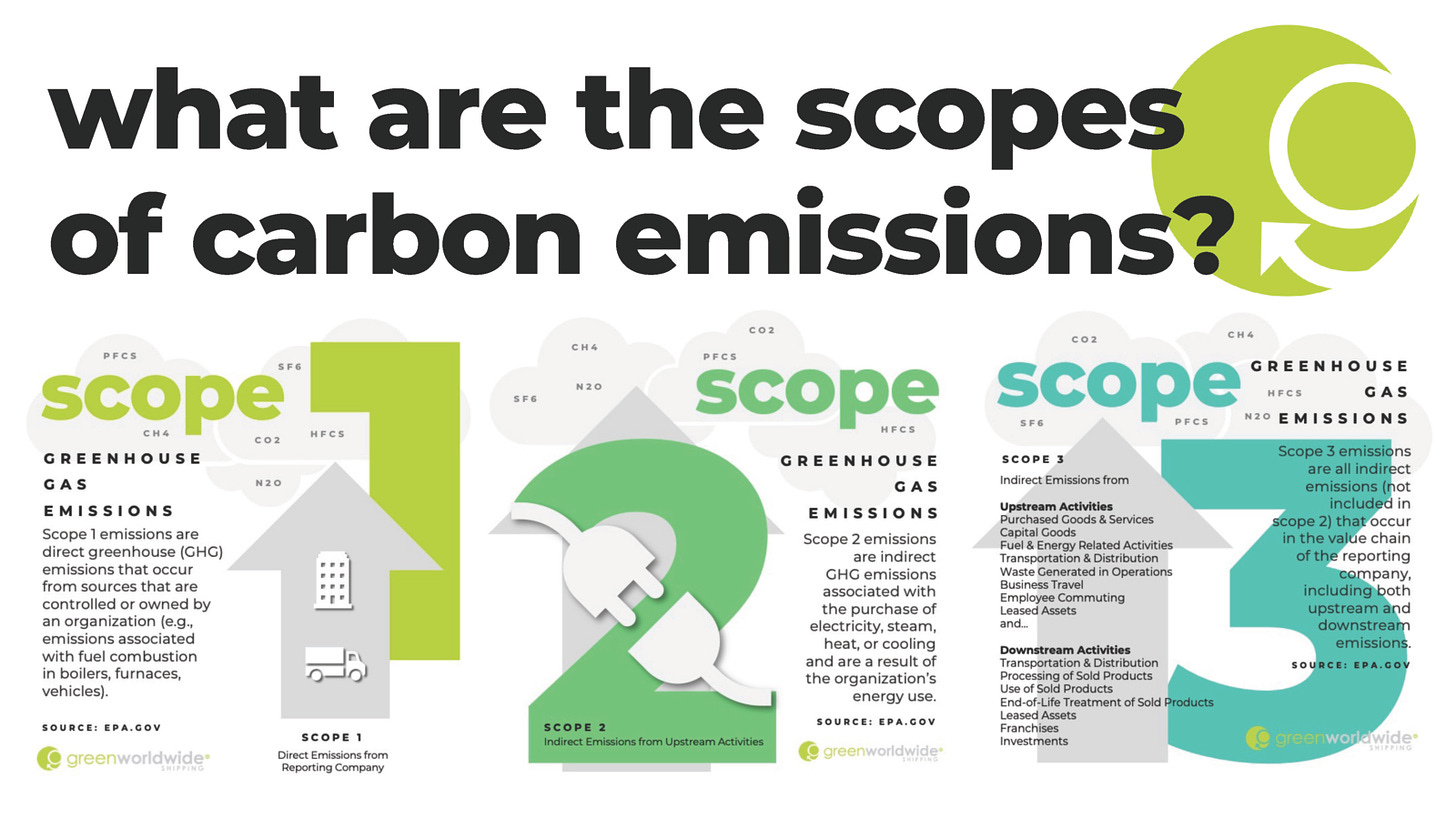

Companies do not need to calculate how efficiency gains into reduced emissions (whether Scope 1, 2 or 3) to know that such steps are worth taking. They will see the results in their bottom line. Bringing efficiency gains into ESG is thus a bit cheeky. Of course businesses want to improve efficiencies and they don’t need a carbon footprint analysis to make the case. If the ESG “game” requires translating efficiency gains into emissions reductions, then that step is easy enough.

Of course, one issue with improved efficiencies is that they mean more profits, more wealth and thus a boost to GDP, which in turn increase emissions. But make no mistake, efficiency gains are hugely important and every company should already be working harder to create more value with less input.

The elephant in the room, the 800-pound gorilla, the big enchilada — that’s carbon intensity. It is a simple mathematical reality that whatever we do on efficiency (and let’s hope it is a lot), we are not going to achieve net-zero carbon dioxide until the carbon intensity of energy approaches zero. That’s right. We need to pretty much eliminate the burning of fossil fuels as a source of energy.

Regular readers here will know from this post exactly how big a challenge it is to eliminate the burning of fossil fuels, and that challenge is illustrated in the figure below.

What can businesses do to help turn around the seemingly inexorable growth in fossil fuel consumption and then accelerate its path to zero? I’ll use the jargon of the ESG industry (in the figure below the bullet points) to offer some suggestions.

Scope One emissions (e.g., those produced by a company’s business). This is where companies have the opportunity for the greatest impact. Search for opportunities to substitute carbon-free energy supply for carbon-intensive supply. Where such opportunities do not exist, demand them from political leaders in whatever jurisdictions your company does business it. In fact, in most cases such demands may be as or more important than what your company can do on its own.

Scope Two emissions (e.g., those produced by a company’s electricity suppliers and partners). Companies have opportunities to select suppliers whose energy inputs emphasize carbon-free sources. Of course, it would be unreasonable for anyone to expect that any company will willingly take a hit to their profits by intentionally relying on inputs that cost more as a result of reliance on carbon-free energy. Of course, one reason for the entire ESG “game” is to create a parallel set of incentives to the profit motive that elevates carbon-reduction as a valued business outcome. Of course, taken to the extreme, this would put a lot of businesses out of business. These parallel incentives help to explain some of the recent push-back on climate ESG.

Scope Three emissions (e.g., those indirect emissions related to a businesses activities, both in its business operations and among its customers). In my views, this is a waste of time — good for ESG consultants, but not so much for accelerating decarbonization or the climate.

So, to summarize, what should the "average CEO" do on ESG related to carbon emissions? Here are my four tips:

Understand both the magnitude of emissions reduction challenge and also the tools in the tool box to make that happen. Educate your C-suite. For instance, if everyone in your company’s leadership does not understand and appreciate the Kaya Identify, your company cannot be making good ESG decisions related to carbon dioxide, increasing the changes that you are just playing the ESG “game.”

Recognize that your greatest influence is on the energy that your company consumes directly. Big companies, especially energy-intensive ones, have the potential for the greatest impact on the trajectory of the carbon-intensity of energy. Understand as well that your greatest impact may not be direct, but the influence you can apply to politicians who make important decisions about society-wide energy policy.

Appreciate that improving the efficiency of your business does have effects on emissions when it results in fewer inputs for the same or more output. But at the same time, improving efficiency is something that you should be prioritize every day (and honestly, no one needs to hear that from me, least of all someone in a profit-focused business in the midst of an energy crisis!).

Know that many aspects of the ESG “game” are just busy work, and to the extent that your company is paying consultants to measure your emissions, it is probably subtracting from overall shareholder value. Tips 2 and 3 above don’t require a lot of investment to document, though certainly some is justified. Scope 3 emissions, as far as I can tell, are just a scam. Demand that regulators clean up the ESG industry and hold it to rigorous standards. Resist the “game.”

I’d love to hear from readers in business, finance and the ESG industry. How do things look from where you sit? I welcome comments from other readers as well.

The rise of an ESG industry focused on emissions reductions is to be expected given the broad societal value that has been placed on weaning the world off of fossil fuels. At the same time, affixing the letters E-S-G onto a business practice does not instantly make that practice worthwhile. Knowing what makes a difference and what does not remains essential.

Paying subscribers to The Honest Broker receive subscriber-only posts, regular pointers to recommended readings, occasional direct emails with PDFs of my books and paywalled writings and the opportunity to participate in conversations on the site. All paid subscribers get a free copy of my book, Disasters and Climate Change at this link. I am also looking for additional ways to add value to those who see fit to support my work.

There are three paid subscription models:

1. The annual subscription: $80 annually

2. The standard monthly subscription: $8 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

3. Founders club: $500 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who have the ability or interest to support my work at a higher level.

Roger, as you might guess, I am highly suspicious of all emissions reduction strategies: Carbon tax, carbon offset, cap and trade, and ESG.

Since my membership in Chicago Climate Exchange and advisory committee for EU-ETS in 2004, I have thought that none of the strategies can accurately provide the material facts of energy consumption for publicly traded companies. You know, measured and verified units on a balance sheet that an accounting firm could sign off.

Ultimately, all strategies are quite vulnerable to gaming, greenwashing, and downright fraud in national and international markets. In particular, ESG has so many different sets of rules and regulations that no two countries have the same sets.

My guess is that the global economy will need to make much better use of “The Cloud Revolution”, Mark Mills recently wrote about.

To be more precise, it is likely to take decades before ESG can be properly monetized, but that doesn't mean ESG cannot be a guide for all.

P.S. You will notice I haven't even brought up the problems of Wall Street’s fiduciary responsibility.

I agree that ultimately our energy system will have to move away from the present heavy reliance on the burning of fossil fuels. There are many reasons for this. Climate Change may or may not be the most important driver. In my opinion it is not.

Our goal should be the facilitation of the steady and intelligent shift to other forms of energy generation, not Net Zero. Net Zero may be a result of this shift but it is a fools errand to focus on it as the main objective.