What a COVID-19 Food Fight Says About Scientific Discourse

Calling out common strategies of partisanship by science journalists

I first wrote a version of this post almost three years ago when I learned that I was blocked on Twitter by some prominent virologists soon after I called for an independent investigation of COVID-19 origins. Since then, I have observed public discussions of COVID-19 origins among virologists continue to devolve into ever-greater depths of name calling, juvenile insults, and more troublingly, efforts to damage careers and reputations.

Of course, I’ve seen this all before up close and personal in public discussions of climate, and as you might guess, I have some thoughts.

Last week, a group of prominent advocates for the zoonosis hypothesis sent a letter to Rutgers University — which employs two prominent advocates of the lab leak theory and who are the subjects of the complaint — demanding that the two scientists be sanctioned for their public comments on X/Twitter.

I won’t get into the details, as they are not really important for this post and are easily tracked down online.1 Virologists on both sides of the origins debate have plenty of room to behave better, but what did catch my attention last week was the immediate intervention of Science magazine, clearly taking the side of the zoonosis-supporting scientists by framing the conflict from their perspective.

Here are some examples of how Science framed its reporting in support of the zoonosis scientists and against the lab-leak scientists:2

Science identifies the zoonosis scientists as “COVID-19 scientists.” The lab-leak-supporting scientists are called “‘lab-leak’ proponents” (and yes, lab leak is in scare quotes).

The zoonosis scientists are characterized as writing “peer-reviewed studies” and in contrast, the lab-leak scientists are characterized as a “constant presence” on X/Twitter — Yet, each moniker could be accurately applied to all of these scientists on both sides.

Science notes: “The [Rutgers] pair has also frequently criticized reporters and editors at Science in social media posts.” The letter writers have also been extremely critical of certain media, but this is not mentioned.

The original version of the Science news article contained a false claim about one of the Rutgers scientists, since corrected, but apparently published without being fact-checked and taken at face value.

Science likens the dispute among virologists to the Michael Mann case — in which Science took an editorial position supporting Mann and excusing his online behavior — writing that the letter writers “aren’t yet planning to file a defamation lawsuit against [Rutgers scientists] Ebright and Nickels, like the one that recently won climate scientist Michael Mann more than $1 million.”3

It is no secret that Science editorially supports the zoonosis theory and has defended the behavior of Michael Mann. When science institutions become partisans,4 it can contribute to further discord and stifle important debate and dissent. Leading institutions of science — like Science and Nature — could simply choose not to become partisans, and serve the entire community, not just those who they favor.

The dynamics of partisanship in science by leading figures and institutions follow what is by now a very familiar playbook. Below are three strategies that signal an unnecessary partisan stance that has the effect of dissuading engagement among those who hold legitimate disagreements.

Associate those with unwelcome views with the bad guys

One strategy is to associate an opponent with political figures or groups who are generally unpopular in the scientific community. Typically, in the United States, these “bad guys” are Republicans or conservatives.

For example, a May, 2021 commentary in Nature about the possibility of a COVID-19 lab leak opened as follows:

Calls to investigate Chinese laboratories have reached a fever pitch in the United States, as Republican leaders allege that the coronavirus causing the pandemic was leaked from one, and as some scientists argue that this ‘lab leak’ hypothesis requires a thorough, independent inquiry. But for many researchers, the tone of the growing demands is unsettling. They say the volatility of the debate could thwart efforts to study the virus’s origins.

The passage explicitly associates the scientists calling for an investigation with “Republican leaders” and presents these scientists and Republicans as being in opposition to “many researchers.” No mention is made here of the fact that the day before this commentary was published, President Biden joined those “Republican leaders” in calling for an investigation of Covid-19 origins.

In many areas of research, scientists lean to the political left (full disclosure: I’m one of them), so tarring any scientist as being associated with Republicans is a not-so-subtle way to signal to the broader community the unacceptability of their views without having to actually engage the substance of their views.5

Following the May, 2021 Nature commentary, virologist Dr. Angela Rasmussen — a signatory to the letter to Rutgers — went even further with the unsavory associations in a Tweet:

Science journalists do not have to adopt an explicit political or partisan framing when characterizing debates within the community — that reflects a choice. Such a framing likely makes sense for a partisan NGO or a politician seeking political advantage, but it does not for a journal that ostensibly seeks to serve the scientific community.

Complain that debate is bad for science and science funding

Another strategy of partisanship is to claim that the unwelcome views are unhelpful or even harmful to certain scientific or political goals. For instance, back in May 2021, some scientists expressed to Nature worry that public discussion of the possibility of a lab leak might harm the ability to perform collaborative virology research based in China.

[V]irologists suggest that such sentiments could lead to more scrutiny of US grants for research projects conducted in China. They point to a coronavirus project run by a US non-profit organization and the WIV that was abruptly suspended last year after the US National Institutes of Health pulled its funding. Without such collaborations, says [virologist Kevin] Andersen, scientists will have difficulty discovering the source of the pandemic.

Who wants to be responsible for their colleagues losing out on a funding or research opportunity?

In science, omertà means avoiding critique that might hurt favored causes of certain, often powerful, scientists or institutional leaders. For instance, last month I attended an event at AEI on the regulation of gain of function research. Following presentations by two leading virologists, a member of the audience asked them a fairly benign but perfectly legitimate question about the importance of identifying COVID-19 origins. Neither of the well-known scientists on the panel responded at all and both sat in stony silence as if the question hadn’t even been asked. The refusal to even acknowledge the question was totally unnecessary. The discussion moved on.

Following the verdict in the recent Michael Mann defamation case Science incorrectly characterized the jury’s decision as a victory for climate science, reframing a tawdry lawsuit that raised many legitimate questions about science and the public, as a broad political cause involving the entire community (and who could possibly be against that?):

The ruling is a victory for climate researchers who have been frequently attacked online over their work and especially for Mann, who has faced the brunt of it, says Lauren Kurtz, executive director of the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund. “The actual facts in this case are just so dramatic.” In a statement, Mann said, “I hope this verdict sends a message that falsely attacking climate scientists is not protected speech.”

In another example, David Fidler, a global-health researcher at the Council on Foreign Relations, argued that the larger aims of geopolitics should trump an investigation into Covid-19 origins:

He says that the escalating demands and allegations are contributing to a geopolitical rift at a moment when solidarity is needed. “The United States continues to poke China in the eye on this issue of an investigation,” he says. Even if COVID-19 origin investigations move forward, Fidler doesn’t expect them to reveal the definitive data that scientists seek any time soon.

Scientific discussion and debates are important regardless who might find them unwelcome for their politics, even if those politics are those of leaders or journalists in the scientific community itself.

Associate legitimate arguments with totally unacceptable views, like climate denial or racism

A third common strategy of partisanship is to associate legitimate expert claims with completely unrelated people or perspectives that are generally viewed to be illegitimate. In climate debates the all-purpose epithet “climate denier” provides a useful and ubiquitous shortcut to signal that an individual should be excluded from discussions related to climate science or policy.

On COVID-19 origins, the May 2021 Nature commentary somewhat bizarrely associated a letter in Science by a range of widely respected experts calling for a more intensive investigation of Covid-19 origins with completely unrelated abuse another scientist received on Twitter, as if the latter somehow invalidates the former:

In the Science letter, the authors note that Asian people have been harassed by those who blame COVID-19 on China, and attempt to dissuade abuse. Nonetheless, some aggressive proponents of the lab-leak hypothesis interpreted the letter as supporting their ideas. For instance, a neuroscientist belonging to a group that claims to independently investigate COVID-19 tweeted that the letter is a diluted version of ideas his group posted online last year. That same week on Twitter, the neuroscientist also lashed out at Rasmussen, who has tried to explain studies suggesting a natural origin of SARS-CoV-2 to the public. He called her fat, and then posted a derogatory comment about her sexual anatomy.

The journalist was suggesting that the Science letter writers calling for an independent investigation should be blamed for some jerk’s behavior on Twitter. That such a contorted line of argument was made in print, much less approved by editors, says a lot about contemporary science journalism.

Of course, scientists too can be jerks on X/Twitter — we are all human — and I’ve seen bad behavior from experts across disciplines, ages, genders, nationalities, and political perspectives. We should all strive to achieve intellectual hospitality, even though we all sometimes fall short. But the reality of jerks on X/Twitter does not mean that contested subjects should not be openly discussed and debated.

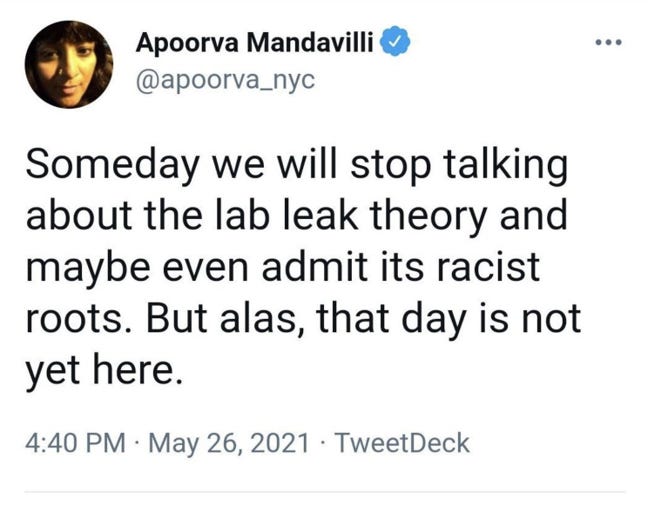

Unfortunately, stopping discussion is often viewed as a feature not a flaw. For example, back in May 2021, in a Tweet (later deleted) following the Nature commentary linked above, a New York Times reporter who covers Covid-19 hoped that discussions of a lab leak possibility would stop, explicitly associating anyone who talks about the “lab leak theory” with being a racist:

The New York Times, Science, and Nature are influential media outlets. When their journalists express that certain areas of debate within the scientific community are improper, it can have a chilling effect on the willingness of experts to openly discuss contested issues.

But in some cases, that chilling effect seems to be the point.

As someone who has experienced efforts to apply the three strategies above to my research and writing, perhaps the best advice I can give to the would-be silencers is to stop wasting your time — it just doesn’t work. The marketplace of ideas is highly resistant to efforts to limit the spread of information and argument.

Even so, public food fights among scientists are bad enough, but when leading institutions of science and journalism join in and take sides, it makes constructive disagreement largely impossible because it fans the flames of politicized science. The last thing the scientific community needs in 2024 is to intentionally bring more politics into scientific debates.

Both democracy and science are better served by open discussions among experts, especially among experts who disagree. Disagreement is not something to be feared. The world not only will survive disagreement among experts, but achieving disagreement is a key to reaching agreement and thus progress in science — And that goes for discovering Covid-19 origins, what we might do about climate change, and pretty much every important issue of out time.

On highly politicized issues, there will always be legitimate science which is inconvenient to someone’s politics. Science journalism in particular needs to reassess its role in the broader scientific community.

Is their function to advance preferred narratives and the political causes of those perceived as being likeminded, while seeking to deplatform or denigrate those holding different views? Or is it to facilitate the opening up of spaces for legitimate disagreement among a wide range of perspectives, both scientific and political, recognizing that such spaces are essential to the success of both science and politics?

I’d like to think the latter.

❤️Click the heart if you think science journalism can do better!

Thanks for reading! I welcome your comments and critique. As always here at THB, practice intellectual hospitality in the comments and let’s keep THB as having one of the best comment sections you’ll find anywhere. THB is reader supported and if you see value in independent research and writing, I invite your support at whatever level makes sense for you.

I am not of the virology community, but I have no problem saying that some combatants on both sides of the origins debate should elevate the level of their engagement. Far more important to me is not one side or the other in the food fight, but actually getting to the bottom of COVID-19 origins — and food fights get in the way of that important objective.

The framing is obvious and uncomplicated — Isn’t this covered in Journalism 101?

Here, Science is wrong, as Mann’s legal proceedings continue, the case has been appealed, and he is facing legal over court costs in a parallel case.

Here, by “partisan” I simply mean in taking one side over another in a legitimate debate, although as I write below, there is often an explicit politically partisan context or overlay.

More recently, Science explained unquestioningly in its defense of Michael Mann’s vicious behavior that Mann equates himself with science and “sees assaults on science as advancing the conservatives’ agenda.” The title of the Science editorial is “Passion is not Misconduct” (to which I’d add, unless it advances the conservatives’ agenda, apparently.)

“The New York Times, Science, and Nature are influential media outlets.”

Exactly.

Media outlets. All about narrative, little about Science.

Science would seem the worst, its title IS misinformation, as shown by its open ended support of Piltdown.

At least it didn’t use the word “deniers”? Small victories?

As to Covid origin, Fauci was involved from the beginning and the slack messaging revealed last year shows him directing the 4 authors of the “Proximal Origins” paper, even though all 4 seemed to agree internally it was likely a lab leak in the end their paper said zoonotic, and then Fauci went on offensive with this new paper pretending to be surprised by its findings.

And also strangely, some or all 4 authors had research grants waiting to be approved on Fauci’s desk.

The coincidences are amazing.

Science

Roger.

Thank you for writing this (and I hope that you don't get on the receiving end of any blow-back).

I have watched both Covid and Climate discussions with some disbelief. Both the zoonosis and lab leak theories are reasonable and both deserve sensible, open, comprehensive and good tempered analysis. The poor behavior and intemperate language benefits no-one, least of all the search for truth.

I am in private sector industry and I doubt there is any business (certainly in my sector - which is oil & gas) that would tolerate the sort of language / behavior we see in some discussion spaces. Any culprits would undoubtedly be asked to desist, leave or face termination.

What is it about academia that tolerates or even enthuses over this kind of behavior ? It leaves me feeling a degree of disgust at academia as a whole in that it cannot get its act together and behave in a grown up manner.