The Politicization of Science Diplomacy

The governance of global public health requires stronger institutions for science advice

Nations around the world are currently considering a “Pandemic Agreement” that seeks to improve preparation for and response to disease outbreaks, drawing on the lessons of COVID-19.

The agreement includes a section on science advice, in the form of a new international science advisory committee, as described in the most recent draft of the agreement, excerpted below.

A key function of the proposed new science advisory committee is to “monitor all types of genetic research” including so-called “gain of function” research on potentially dangerous pathogens. The proposed agreement (again excerpted below) says that beyond monitoring, the science advisory committee will also “supervise research involving pandemic potential pathogens . . . with a view to avoiding biosafety and biosecurity concerns, including accidental laboratory leakages . . .”. There is little offered on how such supervision would be implemented across national, corporate, and military settings.

The idea of independent experts overseeing research and providing important advice to policy makers sounds great. But actually creating institutional mechanisms for advice, monitoring, and supervision in global public health will not be easy or straightforward.

Consider that the international community, notably the World Health Organization and its member states, have been fundamentally incapable of organizing experts to explore the origins of COVID-19. This failure is not the result of a lack of interest, relevant expertise, or the impossibility of learning more, but rather — domestic, international, and science politics.

Exploring the origins of COVID-19 has potentially large implications for the governments of China and the United States, most directly, and regardless of where such an investigation might lead, it will challenge the practices of some scientists, science administrators, and the organizations where they do their work. For many in leadership positions, the mere idea of investigating COVID-19 origins is taboo for fear that it may lead to uncomfortable knowledge.

If we cannot get our collective act together to investigate COVID-19 origins, how in the world can we organize a functioning scientific advisory mechanism under a global Pandemic Agreement?

The failure thus far to investigate COVID-19 origins is an example of the politicization of science diplomacy that I spoke on a few weeks ago at the 2024 annual meeting of the AAAS.

In 2010, the Royal Society and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) defined “science diplomacy” as three functions:

informing foreign policy objectives with scientific advice (science in diplomacy);

facilitating international science cooperation (diplomacy for science);

using science cooperation to improve international relations between countries (science for diplomacy).

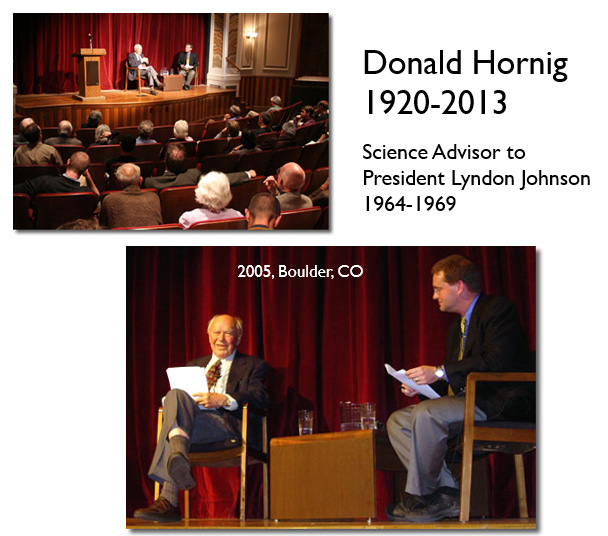

In 2005, as part of a series of interviews of current and former science advisors to the U.S. president, I had the opportunity to discuss science diplomacy with Donald Hornig, science advisor to Lyndon Johnson. Hornig explained that science diplomacy was practiced long before it was named.

Dr. Hornig related several of his experiences in the White House where science became a useful means of diplomacy. One role of science was to project American might to the Soviet Union.

“I first realized that when, in 1964, [Konstantin] Rudnev, a Deputy Premier of the USSR, invited me to come to the Soviet Union as the first half of an exchange, of which he would be the return visitor. We sensed the vested interest in that. I thought it would be a good idea to accept, and the President concurred.

. . . I made the trip in one of the President's airplanes, a 707, accompanied by a distinguished group of industrial scientists. Piore was a vice president of IBM, Hershey was a vice president of DuPont, Fisk was president of Bell Labs, and Holloman was the Assistant Secretary of Commerce. And that made the Russians take us seriously. . .

The visit was, I believe, the first time that it really became clear to the President [Johnson] that science and technology had a role to play in the conduct of foreign affairs.”

Another role for science was to facilitate international collaboration. Hornig told us how the Korea Institute for Science and Technology (still going strong today) got its start in 1965 as last-minute window dressing for a bilateral meeting of U.S. and Korean presidents.

“In the spring of 1965, when President Park Chung-Hee of Korea met President Johnson in Washington.

The day before his meeting with Park, the President called me on the phone saying that the stuff he had from State (that's capitalized, the State Department) was a lot of crap and he wanted something creative. PSAC fortunately was meeting that day, so we closed down our agenda and discussed various possibilities, homing in on the idea of an industrial research laboratory.

… which I presented to President Johnson approximately one — this shows how well the government's organized — approximately one hour before President Park arrived the next morning.

President Johnson liked it. President Park was completely surprised because he thought you had to be notified in advance of these things, but he was pleased. At the end of the meeting, President Johnson had agreed, without consulting with me, to send me, backed by a distinguished delegation — whatever that might mean — to Korea, to see whether the idea could be implemented.

Well, the program was enormously successful. Now, 40 years later, KIST, K-I-S-T, the Korea Institute for Science and Technology, is thriving, has been a model for at least one aspect of development in several countries. It also has a whole string of off-shoots in Korea.”

These anecdotes have in common that science can be very useful as a means for furthering diplomatic ends. Indeed, the stories that are told in the field of science and technology policy almost always have science playing a central, if not heroic, role in geopolitics. Sometimes that is true, as in the examples shared by Dr. Hornig.

Rarely do we discuss the pathological politicization of science diplomacy.1 All of the perils found where science meets politics are present where science meets diplomacy — after all, diplomacy is just a special kind of politics.

At AAAS I highlighted some of these perils:

Compromising scientific integrity to serve diplomatic ends;

The creation of “policy-based evidence;”

Loss of independence of expert advisory mechanisms;

Stealth issue advocacy among experts.

Notably, governments and the scientific community beyond governments have both proven incapable of investigating the origins of COVID-19, which also raises serious doubts about our collective capability to govern and regulate risky research on pathogens. The failure to properly investigate origins is a clear indication that science advisory mechanisms for global public health are simply not fit for purpose. The generic language in the proposed Pandemic Agreement for a new science advisory committee won’t address this shortfall, and may make matters worse by creating a body that is susceptible to becoming deeply politicized.

Last year, based on our EScAPE research project on science advice in COVID-19, I offered some suggestions for the creation of stronger institutions where science meets politics in global public health. Crucially, we need to treat science advice with the same degree of importance and fragility as we do diplomacy itself.

Without stronger institutions, on highly political subjects, rather than bringing science to diplomacy, we will find that science and science advice become just another setting for the conduct of international geopolitics — putting both science and policy at risk.

❤️Click the heart if you think public health needs stronger institutions where science meets politics

Further reading

Pielke, R., & Klein, R. (2009). The rise and fall of the science advisor to the president of the United States. Minerva, 47, 7-29.

Pielke, R., & Klein, R. A. (Eds.). (2010). Presidential science advisors: Perspectives and reflections on science, policy and politics. Springer Science & Business Media.

Pielke Jr, R. (2023). Improve how science advice is provided to governments by learning from “experts in expert advice”. Plos Biology, 21(2), e3002004.

Thanks for reading! THB is reader engaged and reader supported. If you are a free subscriber, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. If you are a paid subscriber, thank you for your support!

At AAAS, I tried out the phrase, the “diplomatization of science,” do you think it’ll catch on?

Roger,

I'm not sure that your going in assumption that 'stronger' <--> 'better'. If history is any guide, I would suggest that the governance of public health requires WEAKER institutions. As we know from history, ANY bureaucratic organization eventually falls prey to the whims of its masters - witness UNRWA's capture by Hamas in the Gaza strip, and Iran's appointment to chair the UN Committee on human rights, and WHO's absolute failure to even TRY to determine Covid-19 origins. I would advocate that the ABSENCE of a global health organization would be much better than any alternative - as then ad-hoc organizations created to address a real issue might actually get something done. A 'global' institution is one of those situations where the cure (WHO relative to C-19) was demonstrably MUCH worse than the disease itself. If the U.S. had ignored everything, including its own CDC/FDA guidance, we would have been MUCH better off.

I like it, and not to be cynical about the scientific enterprise but..

"In 2010, the Royal Society and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) defined “science diplomacy” as three functions:

informing foreign policy objectives with scientific advice (science in diplomacy);

facilitating international science cooperation (diplomacy for science);

using science cooperation to improve international relations between countries (science for diplomacy)."

2 and 3 usually require infusions of $ and seem to be reasons to spend $ on science without hope of utility to anyone.. as the governance of what scientific projects, exactly, are cooperated on- is left to the Science-Industrial complex.