This post is a joint effort with Ryan Maue. Check out his weather Substack, it is fantastic.

Last year the world experienced the most major hurricane landfalls since records are available, tying only 2015, with 11 storms. Does last year indicate that we have reached a new climate-fueled normal? Let’s have a look.

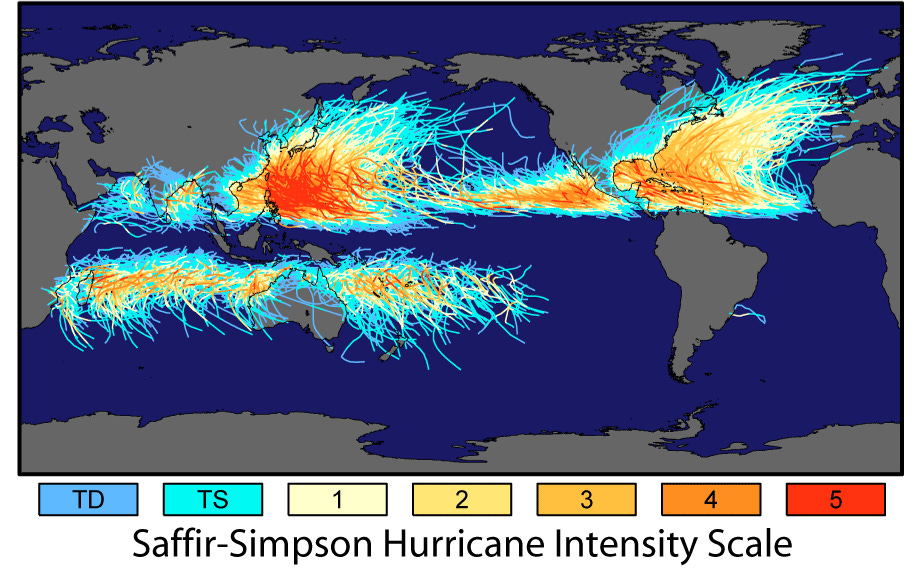

More than a decade ago, Jessica Weinkle, Ryan Maue, and I published the first long-period global hurricane landfall dataset using a consistent methodology. Since then, Ryan and I have updated the dataset annually.

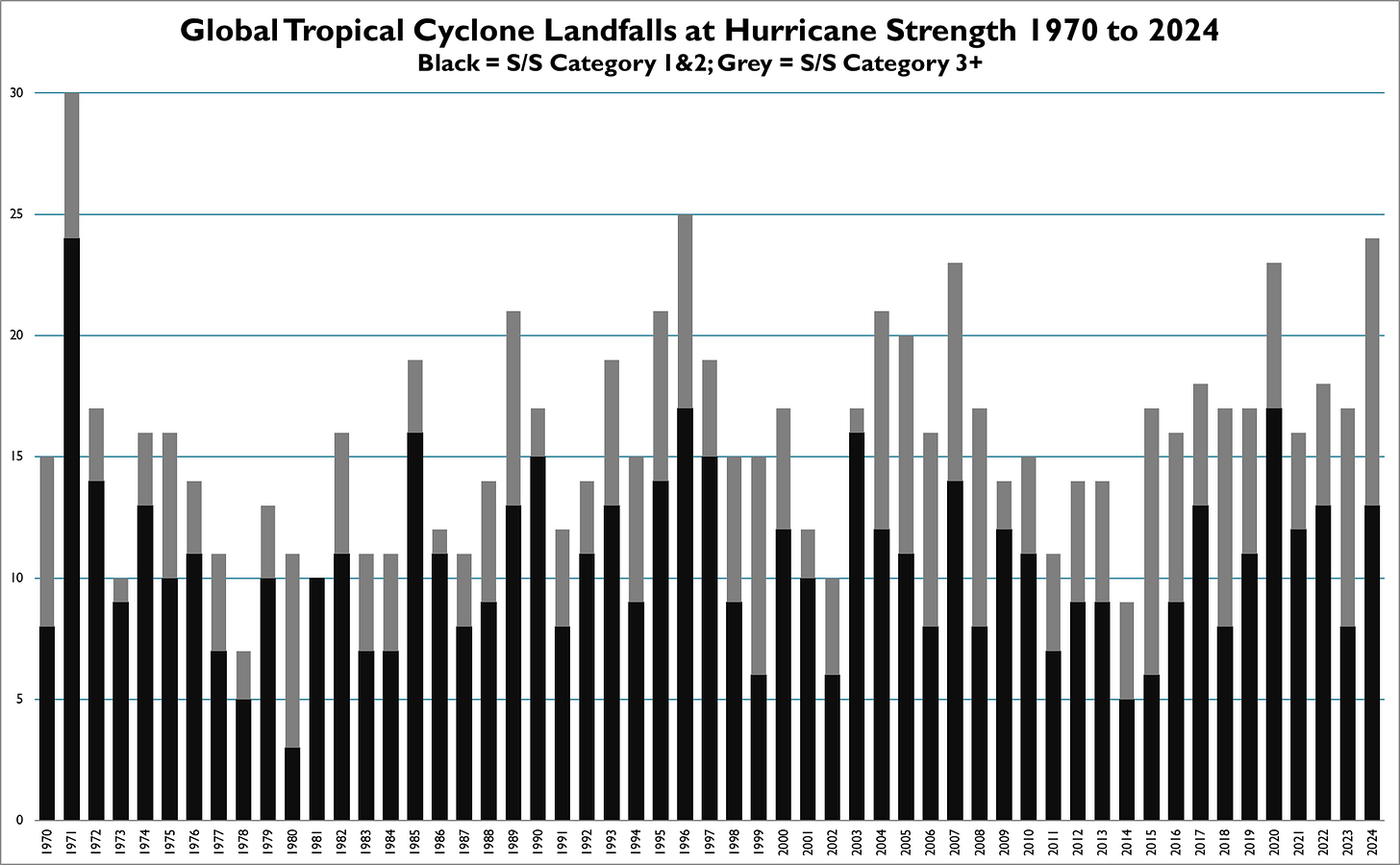

Last year was a very active year for landfalling tropical cyclones of hurricane strength — with 24 total landfalls (S/S Category 1+), 11 of which were major hurricanes (S/S Category 3+). In fact, 2024 saw the third most landfalls around the world of any year since 1970, trailing only 1971 (30) and 1996 (25), as you can see in the figure below.

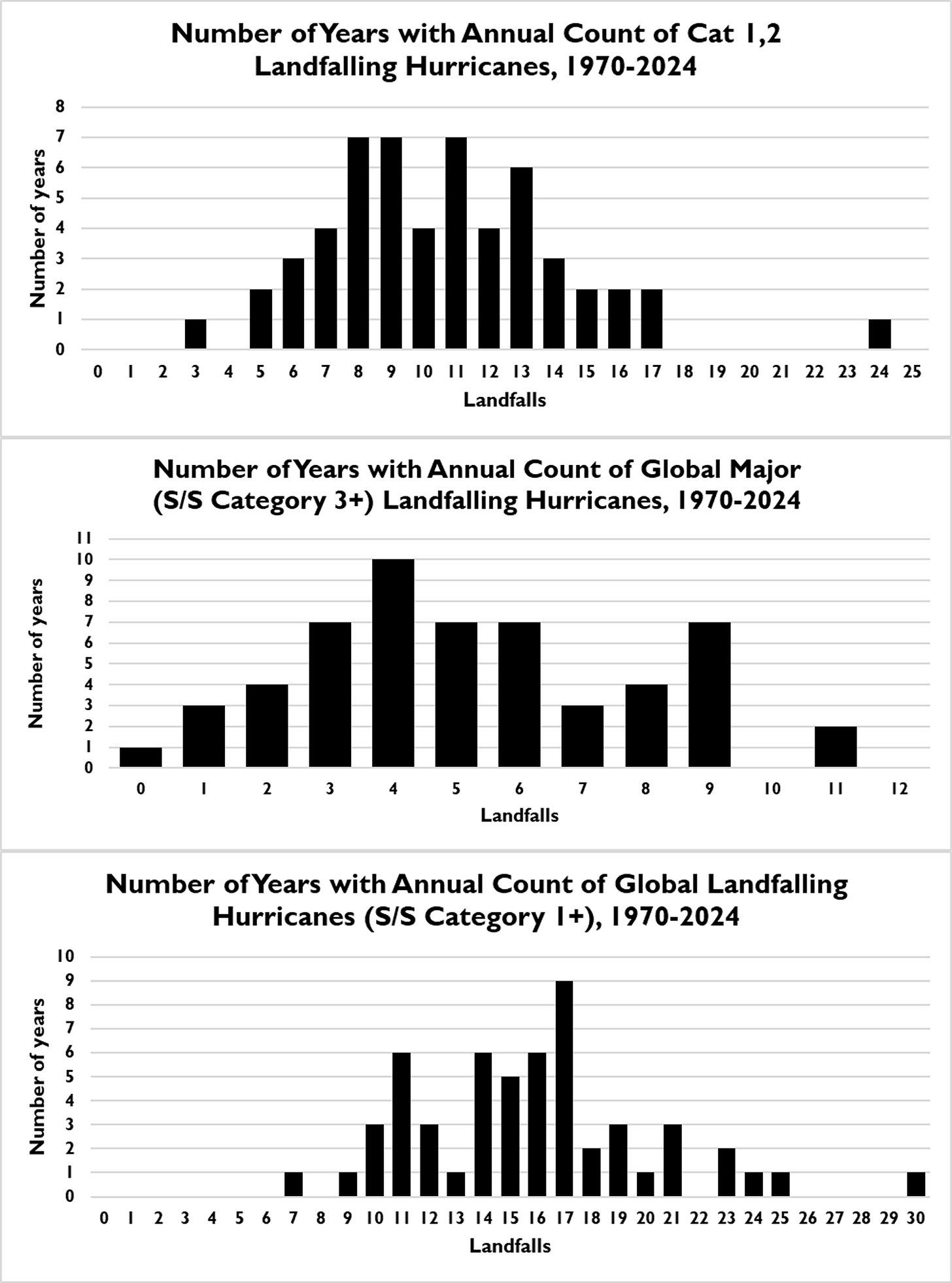

Globally consistent data is available from 1970. The figures below shows that global hurricane landfalls have an interesting set of distributions. The 13 landfalls of minor hurricanes was fairly usual (top panel), but the 11 major hurricane landfalls (middle panel) was an outlier. Taken together, 2024 saw the third most total hurricane landfalls worldwide, since 1970 (bottom panel).1

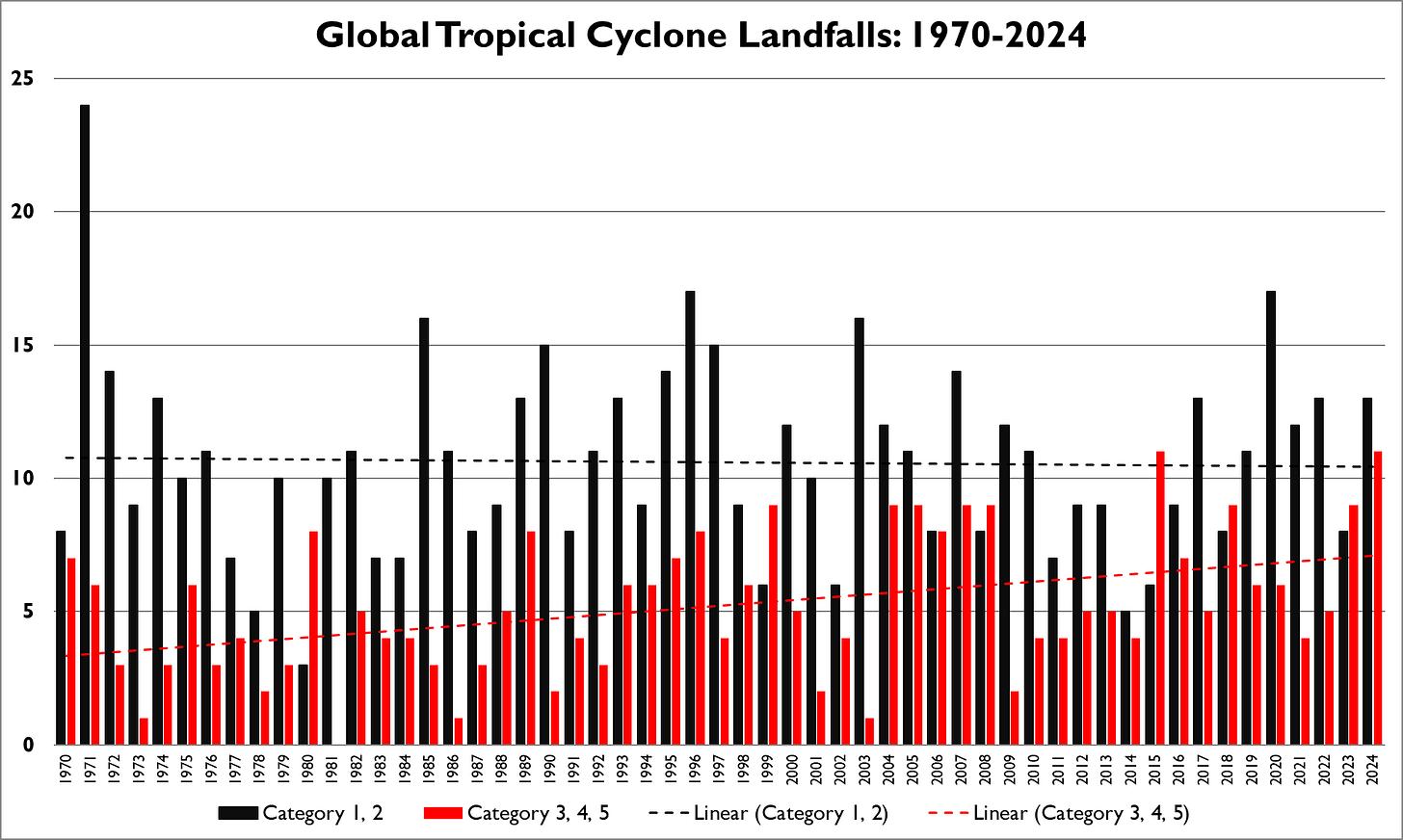

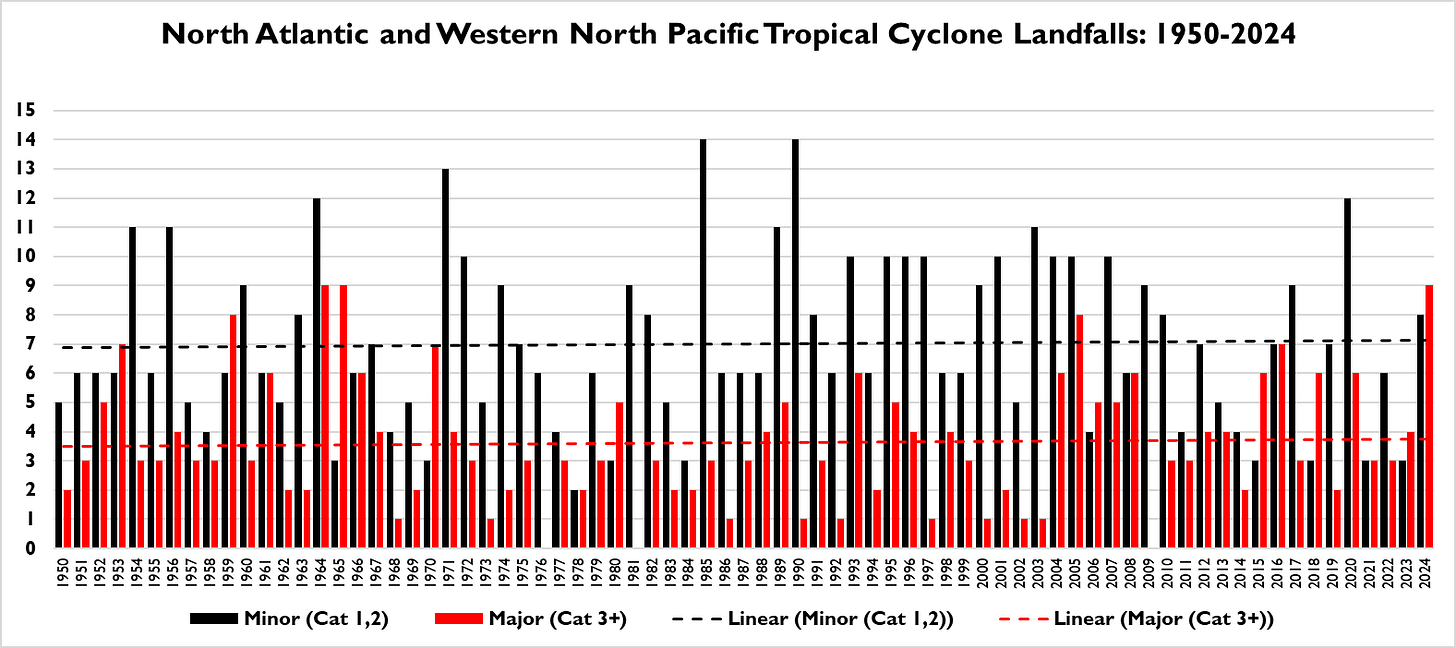

The figure below shows trends since 1970 for minor (S/S Category 1 and 2) and major (SS Category 3+) landfalls.

Since 1970 there is no trend in Category 1 and 2 landfalls, but an upwards trend in Category 3+. Does the upwards trend since 1970 reflect a change in the global statistics of tropical cyclones— and thus a change in climate? And, if so, is that change a result of the emissions of carbon dioxide?

The IPCC AR6 answers no and no:

“There is low confidence in most reported long-term (multidecadal to centennial) trends in TC frequency- or intensity-based metrics . . .”2

What accounts for the IPCC’s conclusion that the available evidence does not support the detection or attribution of changes in the frequency or intensity of tropical cyclones?

The answer has two parts — First, even though globally consistent data is available only from 1970, some ocean basins have time series going back further in time, allowing for a better characterization of variability in tropical cyclone landfalls. Second, landfalls are just a small subset of all tropical cyclones, most of which do not make landfall as hurricane-strength storms.

Let’s take a quick look at each.

The figure above shows hurricane and major hurricane landfalls from 1950 to 2024 for the Western North Pacific and North Atlantic, which together account for more than 70% of global landfalls. You can see that the 1970s were a period of relatively infrequent landfalls, sandwiched by two much more active periods (I did a deeper dive on these data here at THB last year).

Over the entire time series, there is no trend in either minor or major landfalls, indicating that the increase in major landfalls since 1970 is within the range of documented historical variability.

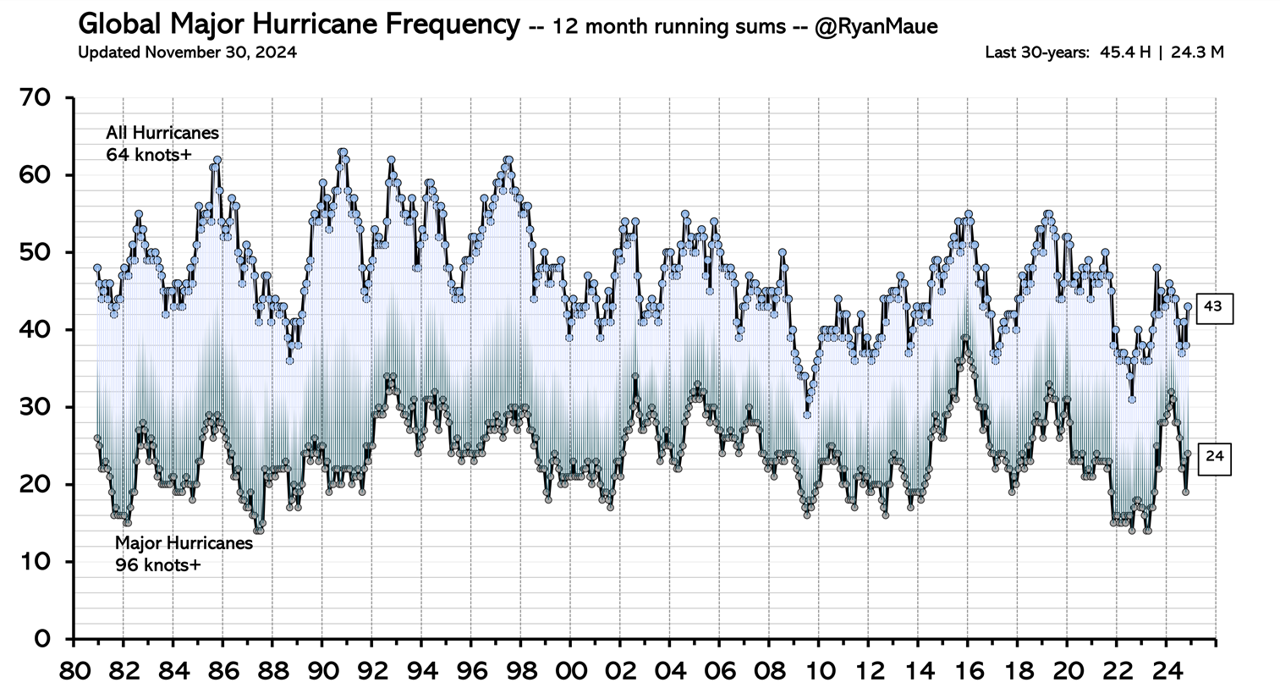

The second part of the answer comes from the data in the figure below — via Ryan Maue — which shows a moving 24-month average number of all (landfalling or not) hurricanes and major hurricanes since 1980, when globally consistent data is available.

The figure shows the large variability in global tropical cyclone incidence. Such variability does not mean that hurricanes are not being influenced in some manner by human activities — including greenhouse gas emissions and aerosols — but it does mean that detecting any such influences today is very difficult or even impossible.

The climate modeling community projects a wide range of possible changes to tropical cyclones by 2100 due to human influences, and various studies often do not even agree on the sign of change. However, one point of strong agreement across such studies is that projected changes are small in comparison to variability, so we should not expect to detect changes in 2025 — For a deeper dive into the methods and math of “time of emergence” see this recent THB post.

What about the frequently-made claim that storms may not be more frequent, but individual storms are becoming more intense?

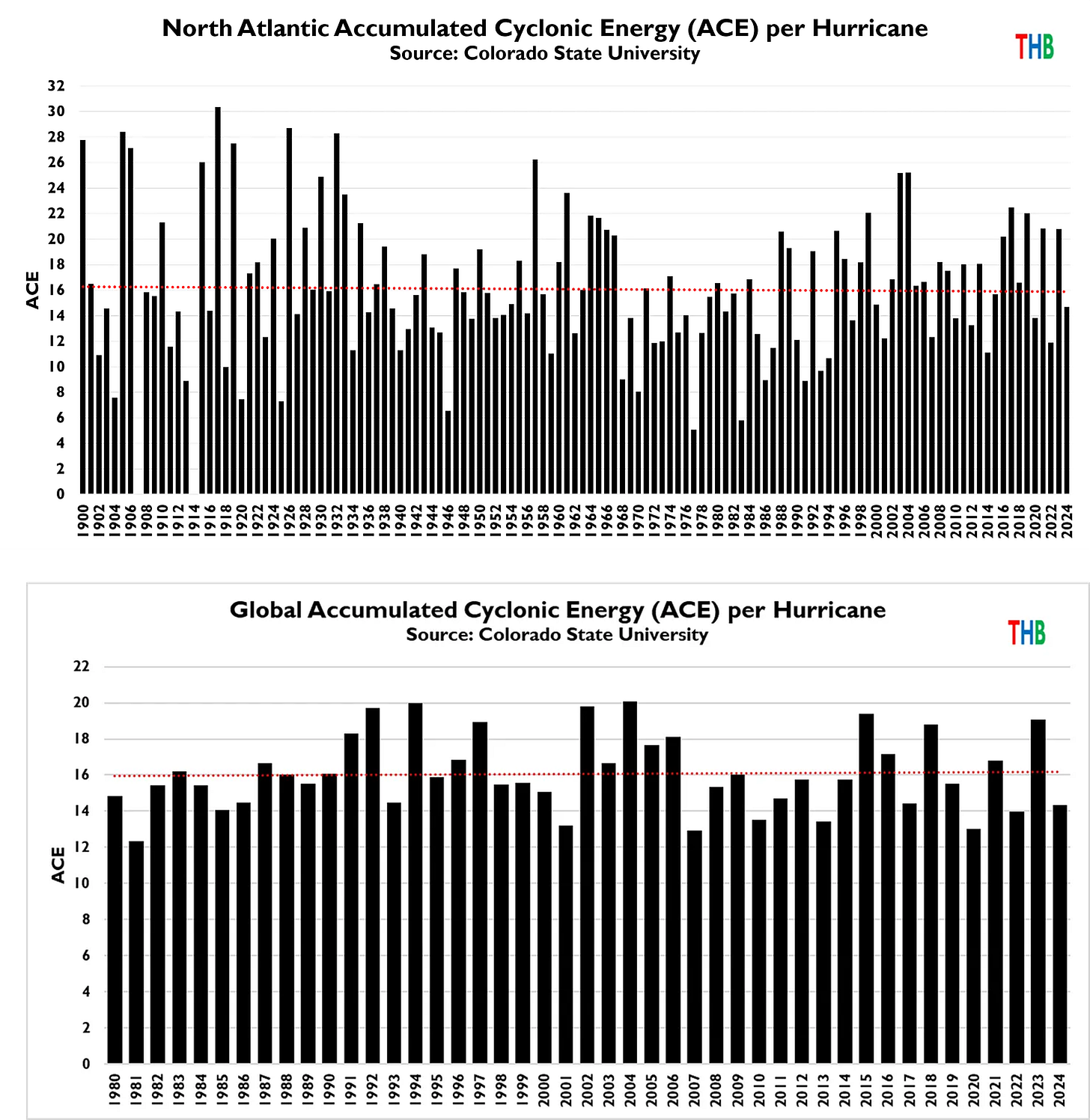

If they are becoming more intense, that also has not shown up in storm data. The figures below — via Colorado State University — show intensity (technically ACE or Accumulated Cyclone Energy) per storm for the North Atlantic (1900 to 2024, top panel) and the globe (1980-2024, bottom panel).

The dashed red lines are the linear trends and they are as flat as a pancake.

Of course, there are plenty enough variables and starting points that it would not be difficult to identify trends in this or that hurricane metric and link those trends to climate change. Such studies are easy to publish and the climate beat loves them. Fortunately, the IPCC has to date played things straight on hurricanes — many others do not.

Bottom line — The record (tying) number of major hurricane landfalls of 2024 is notable, but it is not part of any identifiable trend in hurricane frequency or intensity. The lack of detection of such trends today is exactly what we would expect based on assessed climate research — also known as, the current scientific consensus.

The easiest thing you can do to support THB is to click that “♡ Like”. More likes mean that the algorithm makes this post rise in Substack feeds and then THB gets in front of more readers!

THB is reader-engaged and reader-supported. THB’s aim is to highlight data, analyses and commentary missing from public discussions of science, policy and politics — like what you just read above. A subscription costs ~$1.50 per week and keeps THB running so I can deliver posts like this to your in box several times a week. If you value THB and are able, please do support!

The 30 landfalls in 1971 is quite an outlier.

Under the IPCC detection and attribution framework, there is no attribution possible in the absence of a detected change.

Should not the title read: "The most major hurricanes in 50 years of reliable data"?

Interesting! There is one thing that puzzles me in AR6 (chapter 11): "It is likely that

the global proportion of Category 3–5 tropical cyclone instances and

the frequency of rapid intensification events have increased globally

over the past 40 years." How should one understand this compared to the other quote: "There is low confidence in most reported long-term (multidecadal to centennial) trends in TC frequency- or intensity-based metrics . . .”?