The Energy Transition Has Not Yet Started

Global fossil fuel consumption is still increasing

The latest data on global energy, just released as the Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy (formerly the BP Statistical Review). provides a sobering picture of global energy trends. The data show that the much vaunted “energy transition” off of fossil fuels has yet to get underway.

Since 2015, when the Paris Climate Agreement was signed, global energy consumption increased by 61.2 exajoules (EJ), which is a bit more that the total 2022 energy consumption of the European Union. This increase is very good news for those who lack access to modern energy services. However, that increase was about half due to fossil fuels and half due to carbon-free consumption — bad news for those of us who believe in the importance of decarbonizing the global economy.

This post shares some simple math and readily-understood figure so that you can see the true magnitude implied by calls for a energy transition to net-zero emissions of carbon dioxide from fossil fuels — specifically coal, natural gas and petroleum.

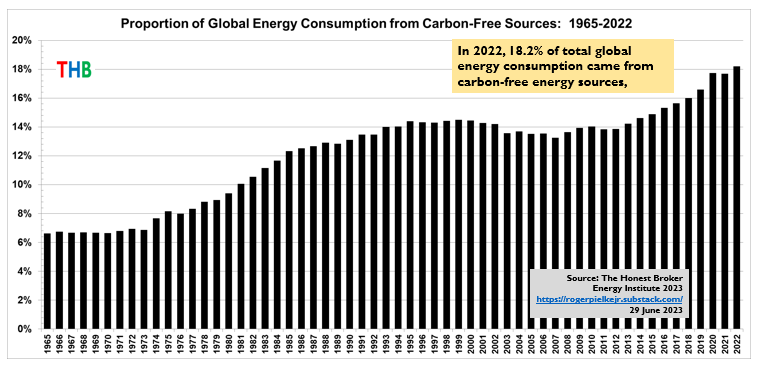

Let’s start with some good news. The figure below shows that in 2022, more than 18% of total energy consumption came from non-fossil sources. That’s the highest it has been in my lifetime.

Over the past decade, carbon-free energy consumption has increased as a proportion of total consumption from less than 14% to above 18%. Of course, getting to net-zero requires going from 18% to 100%. If the rate of increase in the overall proportion of carbon-free energy consumption observed over the past decade (+4%) were to continue, the world would hit 100% carbon-free energy in about 2253.

A crucial detail that is often overlooked in climate policy discussions is that it is not the deployment of carbon-free energy that reduces emissions — it is the retirement of fossil fuel energy.

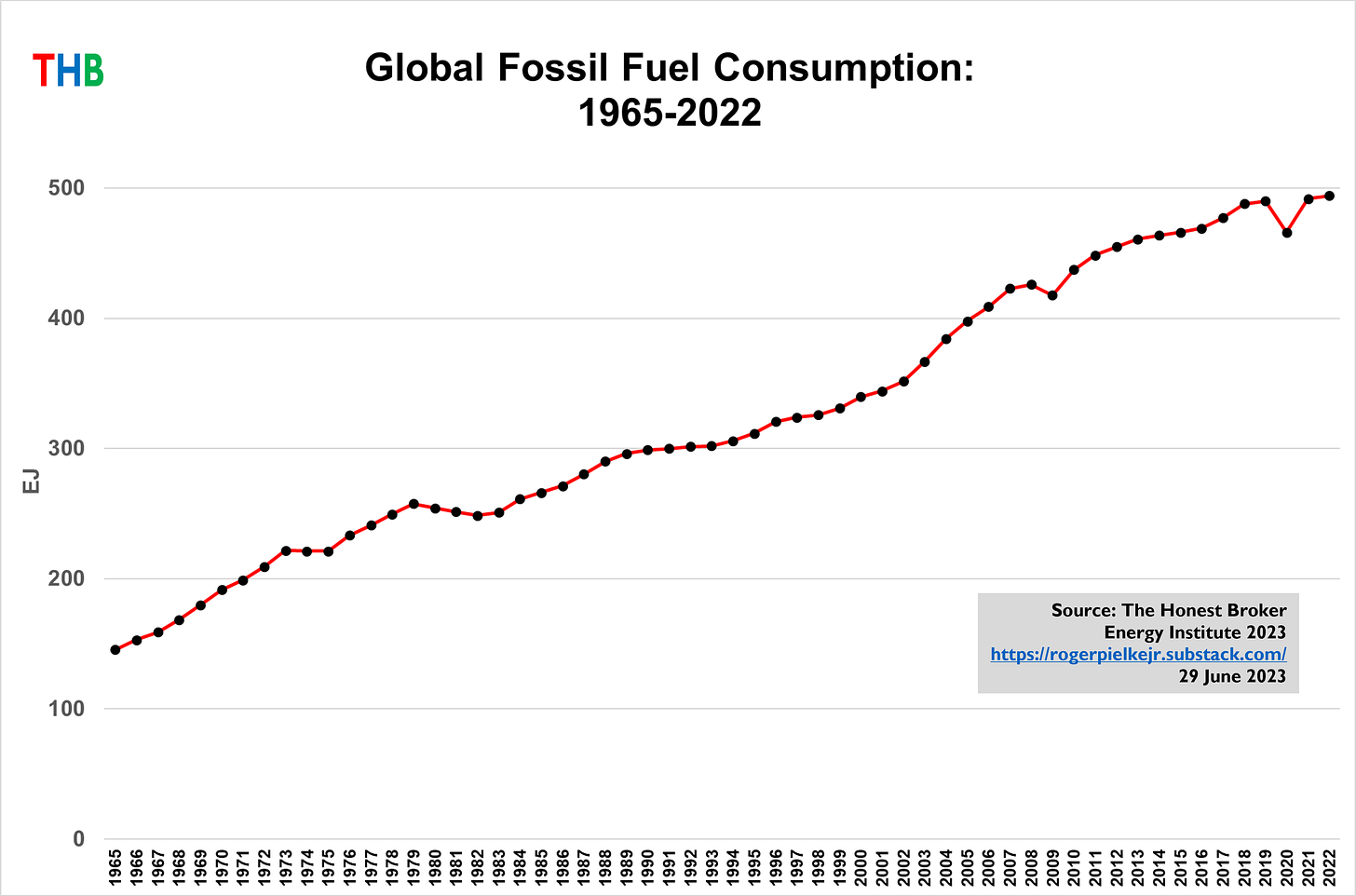

The figure below shows that while fossil fuel consumption has slowed its rate of increase over the past five years, it still continues to increase. Earlier this year I anticipated that overall fossil fuel consumption in 2022 would come in less than 2021 — I was wrong. The increase from 2021 to 2022 was a paltry 0.5%, but an increase nonetheless. You can see the latest data in the figure below.

BP projects peak global fossil fuel consumption before 2030, but we haven’t hit the mountaintop quite yet.

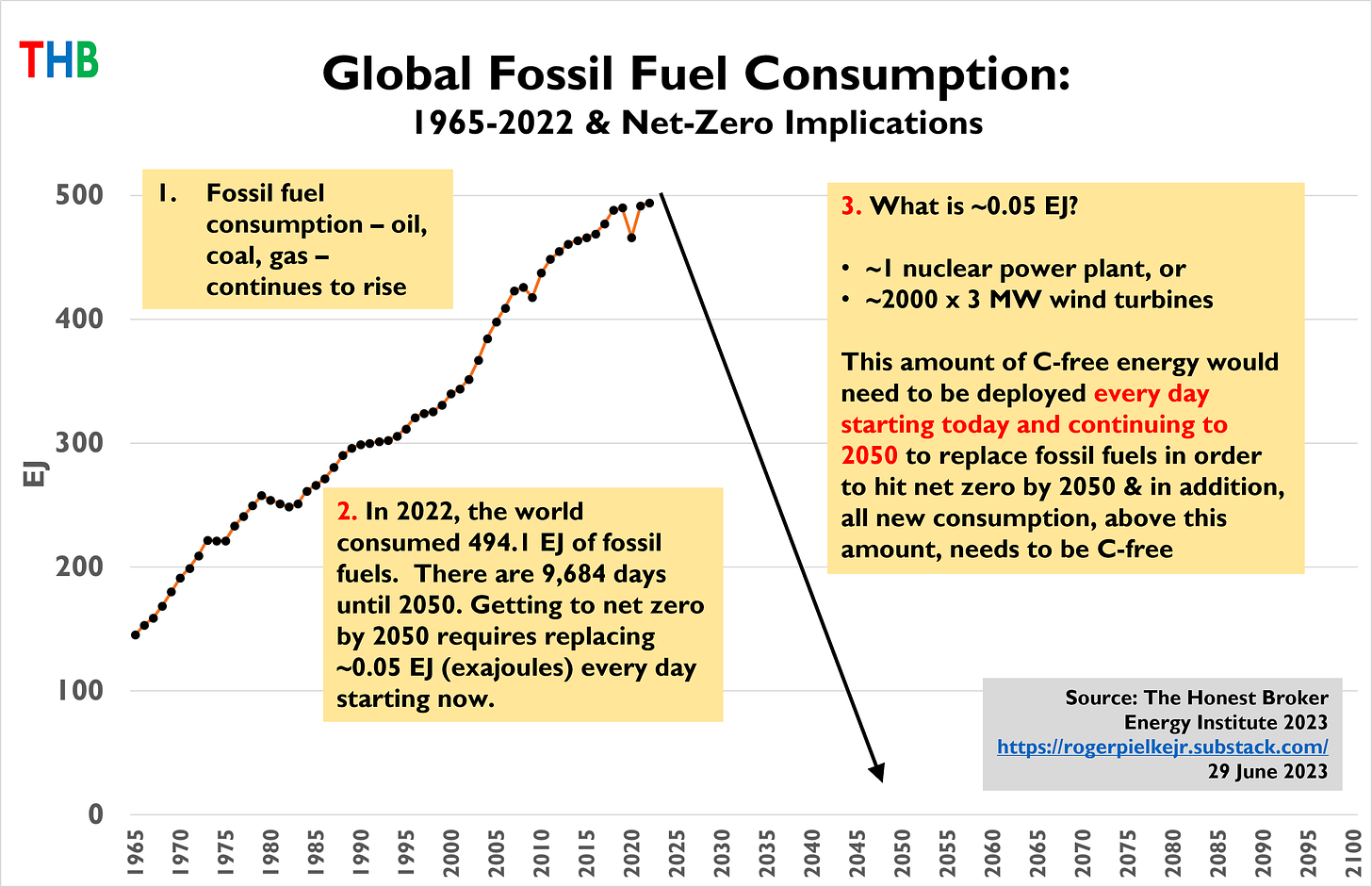

The figure below shows what it would take to reach net-zero fossil fuels by 2050 (which might include the continuing use of fossil fuels alongside carbon capture). I use 2050 here, an oft-mentioned target, but obviously we could use any year year to generate implied numbers for rates of change.

Every year that fossil fuel consumption increases or does not decrease at the pace necessary to hit a 2050 target, the net-zero challenge gets larger in terms of both the overall magnitude and the implications for rates of increases in carbon-free energy consumption and for fossil fuel retirements.

Achieving net-zero fossil fuels by 2050 requires the deployment of the equivalent of 1 nuclear power plant per day — starting today and continuing every day until 2050. That’s the equivalent of about 2,000 x 3 Megawatt (MW) wind turbines (note: according to the U.S. Department of Energy the average capacity of wind turbines deployed in the U.S. in 2021 was 3 MW).

We might vary the assumptions, factoring in things like unnecessary heat loss, global growth in overall energy consumption, etc.. When we do so, plausible deployment rates might range from a nuclear plant-equivalents every-other day to 3 every two days. The conclusion here is robust to various assumptions — Transitioning off of fossil fuels is an absolutely massive, herculean challenge that requires rates of change in global energy never before achieved.

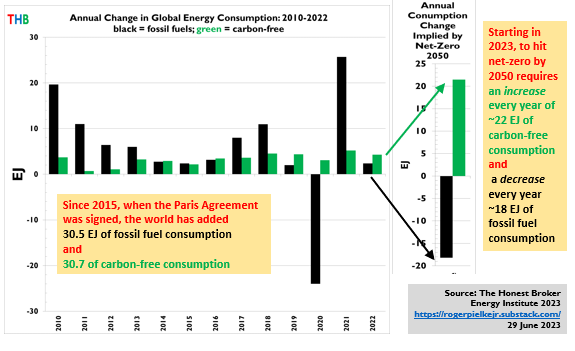

This conclusion is apparent in the last figure that I’ll share today, below. This figure shows the annual change in global energy consumption since 2010 broken down by fossil fuels (in black) and carbon-free energy (in green). You can see that in every year, fossil fuel consumption increased except during the pandemic year of 2020.

The panel on the right shows the rate of annual change implied by a net-zero target for 2050. Consumption of carbon-free energy would have to increase by more than 20 EJ to account for replacing fossil consumption and account for growth in global energy consumption. Correspondingly, fossil fuel consumption would have to drop by almost 20 EJ. We might quibble over the exact magnitude of carbon-free deployment necessary, but there is nothing to quibble over on the implied necessary rate of retirement of unmitigated fossil fuel consumption.

Remember — It is the retirement of unmitigated fossil fuel consumption that reduces carbon dioxide emissions not the deployment of carbon-free capacity.

Fossil fuel consumption has yet to decrease. Until it does, the race to transition global energy consumption remains in the starting blocks.

Methodological note: The numbers here are a little different than those I’ve used in past years, reflecting reader feedback on the size of a generic nuclear power plant (1.75 GW capacity), average current wind turbine capacity (3MW) and capacity factor (0.30). I encourage everyone to make their own assumptions and derive their own estimates. Only by working with the numbers can we truly understand what is implied by an “energy transition.”

I welcome your comments! Please hit that little heart above, share on your favorite social media and ReStack. Consider referring a friend. If you are already a subscriber, Thank you! If not, please sign up and join the community.

The challenge for wind-energy (or solar-energy) installation is even more massive than you indicate because, in addition to the huge number of wind turbines that have to be built, an even huger number of batteries (or other storage devices) have to be built. I think the storage is an even bigger challenge than the carbon-free generation.

A few comments:

• "Achieving Net Zero by ____" is about as defensible as "Limiting global temperature increase to 1.5 (or 2) C by _____."

• I freely admit that decreasing the pollution associated with burning coal (and natural gas, to a lesser extent) would be a good thing. But preventing those living in developing countries from using fossil fuels if those are the most readily available to them would be, quite frankly, immoral.

• I've said it before and I will continue beating the drum: the US needs a sensible plan to phase out of fossil fuels, if that's to be our energy policy. California's periodic brownouts caused by the intermittency of solar and wind - exacerbated by drought-impacted hydro - further exacerbated by the "feel good" closures of fossil and nuclear plants - should be grim reminders that we don't have a plan, but rather posturing politicians making policy.

• That plan MUST consider both generation and transmission. There are significant efficiencies possible if we upgrade our aging transmission system.

• The silliness of effectively banning gas stoves, urging people to eat less meat, and so on signals the triumph of emotion (it feels good) over reason (it will make a real difference).