This is an ungated post in my weekly memo series, which are typically for paid subscribers only. Please share and consider a subscription to The Honest Broker, at any level. This community is growing fast and the comments are insightful and respectful. I am learning a lot and I hope you are also. For new readers, you can see a recently updated “reader’s guide” here.

My review of Alex Epstein’s Fossil Future led to a lot of interesting comments and discussion. It also prompted me to dig into some data, and I’ve seen a few things I hadn’t noticed before. Specifically, the world appears to be on the cusp of a major inflection point – peak fossil fuels.

Consider the following three lines of evidence.

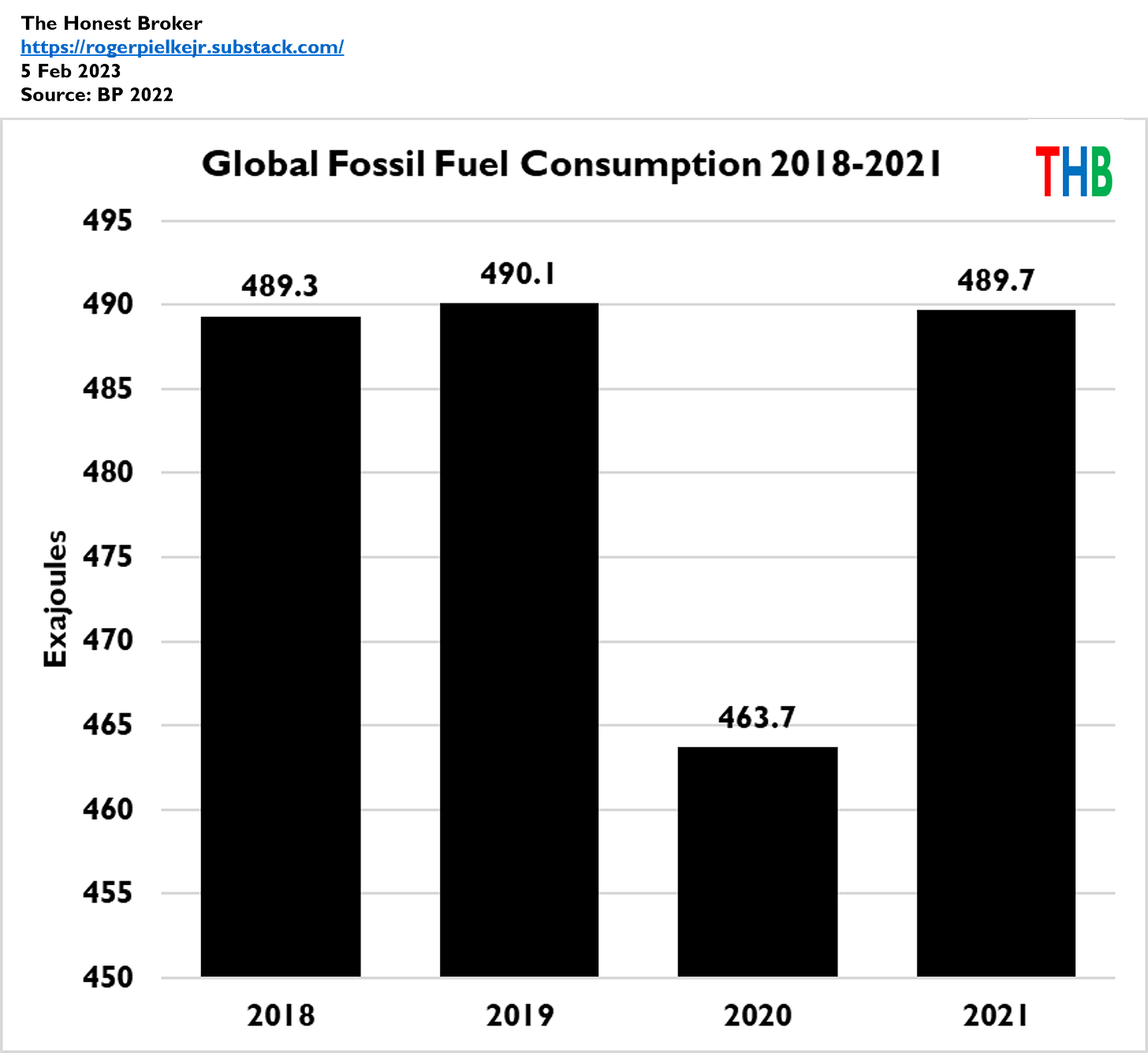

First, according BP, since from 2019 to 2021 global fossil fuel consumption remained level, with the exception of the big drop in 2020 due to the pandemic. According to the World Bank, global GDP (in PPP) was 5.7% higher in 2021 than in 2018. You an see the recent plateau in the figure below.

There has only one other period (since 1965) that the world saw a four-year plateau in overall fossil fuel consumption, and that was following the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Total global oil consumption dropped by more than 11% from 1979 to 1983. Oil consumption increased in every year following 1983 until the global financial crisis in 2008-2009.

The 2018-2021 plateau is thus unprecedented. Will 2022 come in above or below 2021 levels of fossil fuel consumption? Take the under.

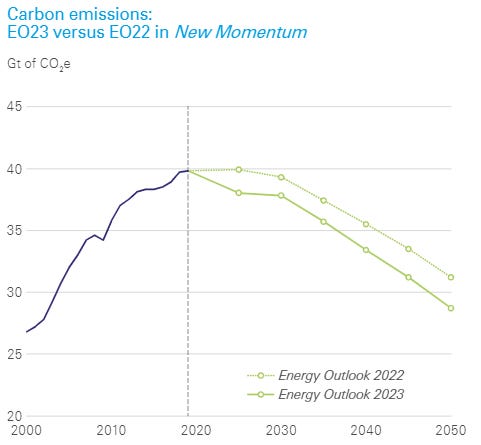

A second line of evidence can be found in the BP 2023 Energy Outlook, released last week, which projects peak global oil consumption has already happened. Under its New Momentum scenario that is “designed to capture the broad trajectory along which the global energy system is currently travelling,” BP projects a long-term decline in oil and coal. Future policies or technological advancements could accelerate these projections.

The new downward revision in oil and gas consumption in coming years leads BP to project that global carbon dioxide emissions will peak by 2025, and decline rapidly thereafter, even without additional policies.

From 2019 to 2050 BP projects in its New Momentum scenario that coal and gas consumption will decrease at rates of 1.6% and 1.0% annually, while natural gas increases at a rate of 0.5% annually, collectively amounting to a steady decline in overall fossil fuel consumption.

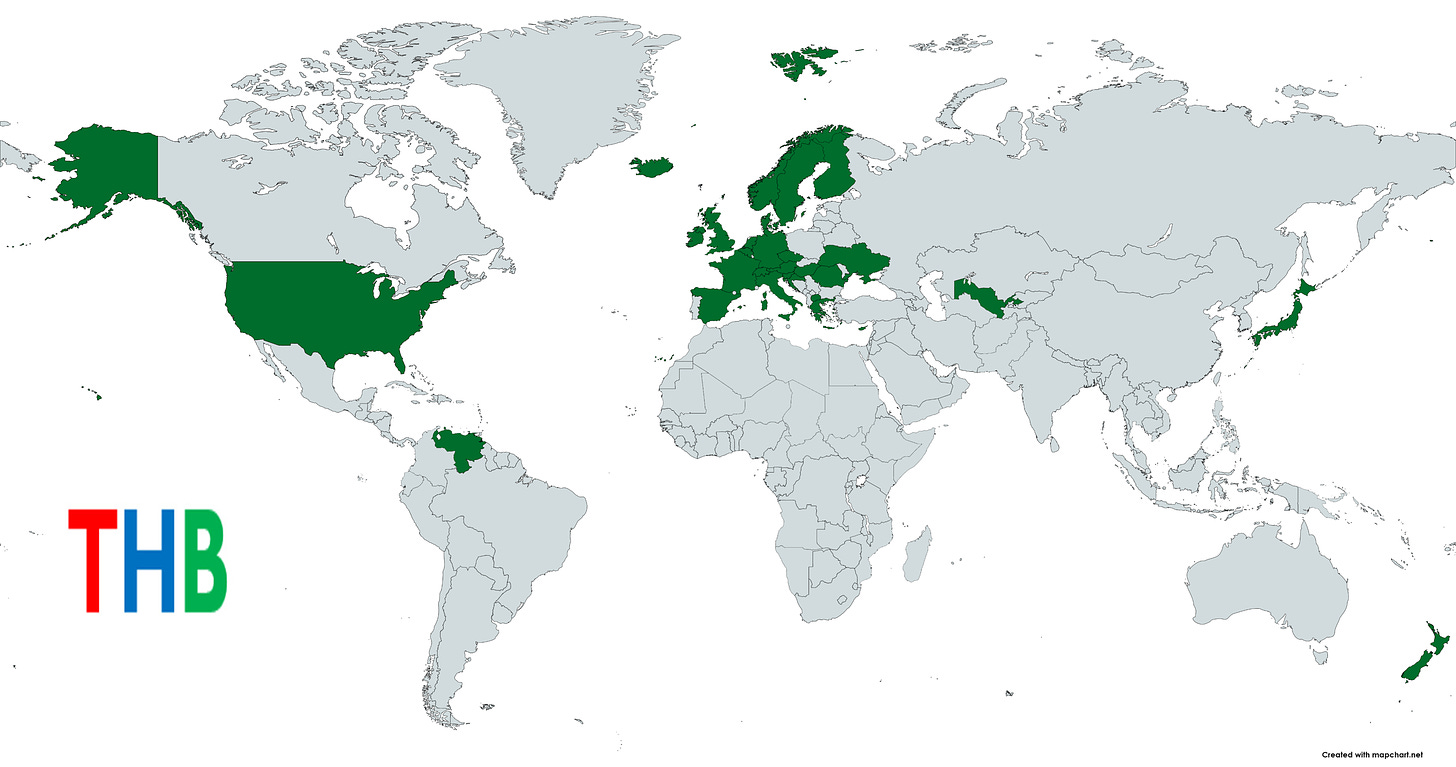

A third line of evidence can be seen in the map below. The countries in green are those that reduced their overall fossil fuel consumption from 2000 to 2021 — led by the US, UK, Japan and Germany. In 2021 these 32 countries represented about 50% of global GDP.

The map shows clearly that future fossil fuel consumption — and whether it grows or falls — will be determined by countries that today are growing their economies and do not yet have the wealth of the countries of the OECD. China and India, in particular are central, but so too (and hopefully sooner rather than later) will be the 50+ countries of the African continent. The long-term plan for reducing fossil fuel consumption is thus — let’s make everyone rich.

But don’t miss the significance of this map — already, countries representing half of the global economy have seen fossil fuel consumption decrease this century. Will the club of countries that reach peak fossil fuels grow or shrink in coming years and decades? Take the over.

Forecasting the future is never easy, and failed forecasts are fun to look back at and have a laugh. At the same time betting against technological innovation is itself a forecast. I don’t know if the world has reached peak fossil fuel consumption, but I’m comfortable claiming that we are getting pretty close, if not there already.

Your thoughts?

Thanks for reading, participating and supporting. Coming soon, Chapter 2 of The Climate Fix for debate and discussion. You can catch up on Chapter 1 here. If you are already a subscriber, please consider gifting a free subscription to that special someone who might enjoy The Honest Broker.

The countries in green on the map currently represent half the global economy.

The other countries represent 85-90% of the world's population. To make these countries as rich, or half as rich, will require a big increase in need for energy. It is very unlikely that this energy will come from sun or wind ...

Trends are interesting, but digging into the details is more enlightening.

Reduction of fossil fuel consumption in rich nations has been driven by a variety of factors, particularly populations that are declining or increasing only very slowly. Offshoring of heavy industry and its associated emissions is common in this group.

Venezuela's economy has cratered, while European consumption has been impacted by the Russian war as well as aggressive renewables development - both of which are producing energy crises and big questions about whether the reductions can be sustained while repairing economies.

Iceland and New Zealand have small populations and immense renewable resource potential, far out of proportion to larger nations.

Meanwhile, the appetite for increased fossil fuel consumption in the populous, developing nations is accelerating, along with their appetite for other energy sources, including renewables and nuclear.

It's clear that FF demand will continue to increase in lower-income nations, and it's apparent that at least some of the mechanisms of demand reduction in high-income nations have run their course and may even be reversed for economic stability. Renewables (and, one hopes, nuclear) will continue to increase, but they are only beginning to confront massive supply-chain and critical materials challenges.

BP and others have many energy forecast scenarios. It's safe to say there are few if any left that forecast massive increases in FF consumption by 2050, but there are plenty (and should be more) that reflect current challenges to energy transition - which will delay peak FF consumption.