In my recent courses on energy policy, I explain that discussions of energy technologies can be lot like discussions of sport, where everyone has their favorite team. Nuclear, wind and solar each have their supporters and opponents who spend a lot of time on Twitter and elsewhere promoting the positives of their favorite energy technology and downplaying any negatives. In fact, much of what passes for energy policy discourse is just the cheerleading or booing of different “teams.”

Fossil fuels have their fans as well, despite being widely looked upon as evil — much like the New York Yankees or Man City. With Fossil Future: Why Global Human Flourishing Requires More Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas--Not Less, Alex Epstein seeks to do more than cheer for fossil fuels, he seeks to make an argument for why the world needs to abandon efforts to eliminate the burning of fossil fuels, and instead, expand their consumption.

Throughout the book, Epstein gets a lot of things right, and discusses lots of topics apart from his main argument (bloating the book, unfortunately). Ultimately, he gets the most important part of his argument wrong. Global human flourishing — a worthy aim to be sure — does not “require more oil, coal and natural gas.” That is not my counter opinion; that is in fact what the evidence already shows.

Epstein explains that his training in philosophy has well prepared him to make a strong argument, which he asserts the broad and diverse coalition of opponents of fossil fuels has only done in part. Specifically, Epstein argues that the widespread political consensus that fossil fuel use must be reduced — for many, to a level consistent with net zero carbon dioxide emissions — is wrong because it ignores the unique benefits of fossil fuels and their manageable “side effects.”

Epstein’s argument conflates correlation with causation and also means with ends.

Let’s start with means and ends. Epstein is absolutely correct to argue that energy consumption is fundamental to human flourishing. He draws upon a range of well established data — similar to work of Hans Rosling and Our World in Data — to show that by many indicators the human condition has improved over centuries and decades, dramatically so.

The most important reason for this broad advancement in human flourishing, Epstein argues, is the burning of fossil fuels and application if their byproducts. It is undeniable that since the Industrial Revolution, global development has been powered almost completely by increasing consumption of fossil fuels. That means that every metric of progress in human flourishing has been correlated with increasing fossil fuel consumption.

But fossil fuels are a means to producing energy and energy services, they are not an end in themselves. The entire point of policies today focused on dramatically reducing fossil fuel consumption is to try to eliminate their downsides (like pollution, insecurity, and economic risks), while maintaining all the positives that they do provide (i.e., the basis for energy services and modern society). In fact, if energy policy cannot maintain the positives during such a transition, there won’t be any transition — that’s an “iron law.”

Put slightly differently, we can fully accept the central and perhaps even unique role played by fossil fuels in global development in the past several centuries without accepting claims that history is also destiny.

Epstein dismisses many forecasts made by energy and climate experts (including the entire IPCC), as the product of a corrupted “knowledge system.” I have a lot of selective sympathy for situations where experts get off track (RCP8.5 anyone?). But Epstein throws out the baby with the bath water. Just because experts are sometimes wrong does not mean that they are always wrong. I’ve often said that if the IPCC didn’t exist, we’d have to invent it. Epstein tackles a lot of issues with a sledgehammer, when a scalpel would have been a better choice.

Epstein comes down hard on predictions made by others, but is quick to advance his own set of forecasts. Among them, specifically he argues that (pp. 203-4):

There is “virtually no possibility” that “alternatives to fossil fuels will become partial replacements for fossil fuels, providing so much cost-effective energy that there is actually a decline in fossil fuel use despite growing energy needs”

It is “virtually impossible” that fossil fuel “alternatives will rapidly become total replacements for fossil fuels, supplying all the energy fossil fuels provide today plus all the additional energy that will be needed by an empowering world.”

These predictions, made with utmost confidence, are the keystone of Epstein’s argument. Without these predictions coming true, the case for fossil fuels simply falls apart. We have an expanding fossil future, he argues, because we have no choice — that is, if we wish to continue with the level of energy services that the world currently enjoys, much less broaden availability of energy services to those who lack such access.

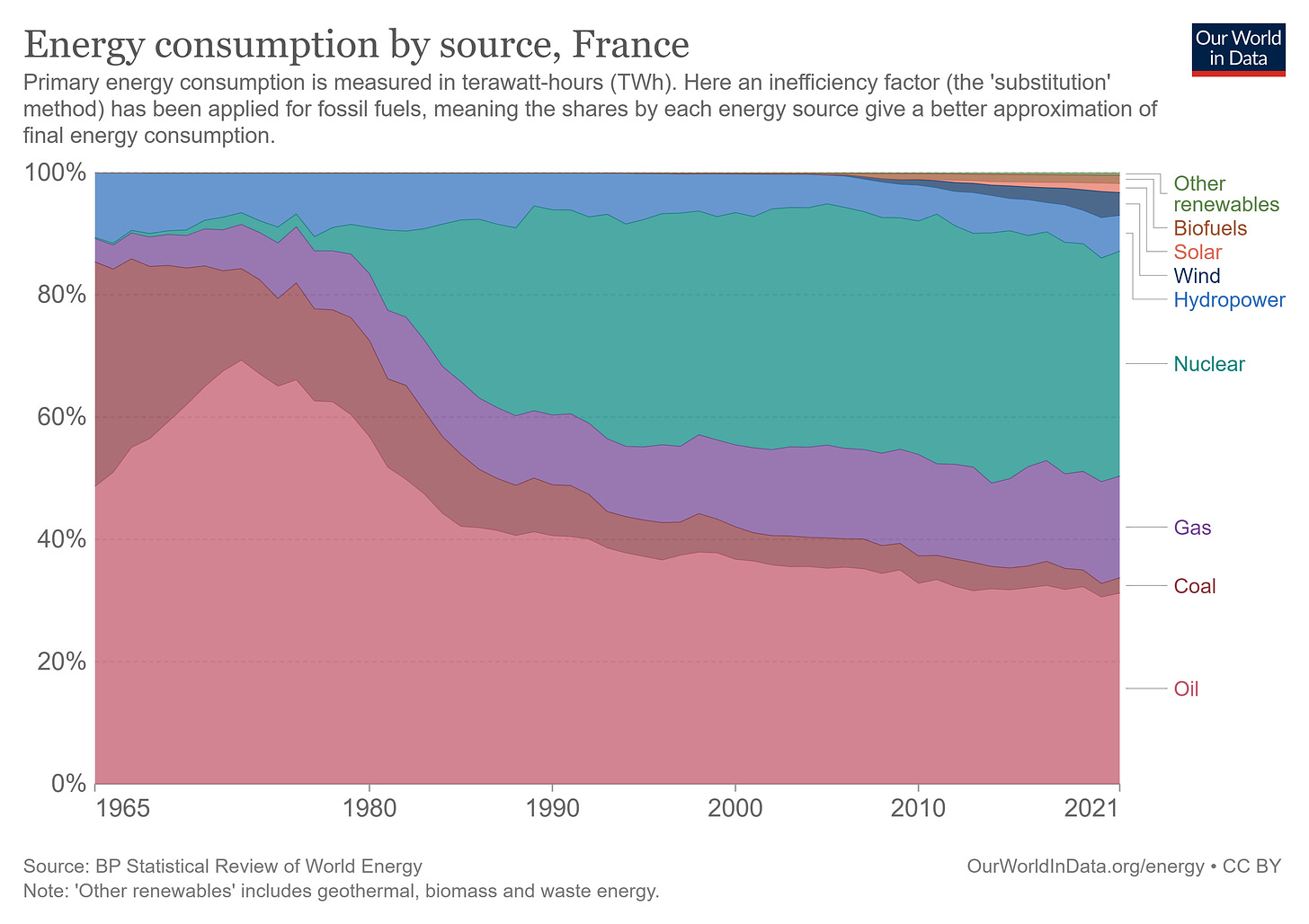

As a matter of empirical evidence, Epstein is just wrong. There are countless examples of the partial replacement of fossil fuels in large-scale energy systems. One example will suffice. Consider France.

The figure above shows how France replaced fossil fuels — which in 1965 comprised about 90% of its total energy mix — with non-fossil energy such that in 2021 fossil fuels comprised less than 50% of its total energy mix. I like to cite France in class because it is an actual, real place (and quite a nice place as well). Its energy history is undeniable. It has reduced reliance on fossil fuels while growing its economy.

More generally, the International Energy Agency projected in 2022, for the first time, that global consumption of fossil fuels will peak this decade and start to decline under current policies, and even faster under policy commitments:

The STEPS in this Outlook is the first World Energy Outlook (WEO) scenario based on prevailing policy settings that sees a definitive peak in global demand for fossil fuels. Coal demand peaks in the next few years, natural gas demand reaches a plateau by the end of the decade, and oil demand reaches a high point in the mid-2030s before falling slightly. From 80% today – a level that has been constant for decades – the share of fossil fuels in the global energy mix falls to less than 75% by 2030 and to just above 60% by mid‑century. In the Announced Pledges Scenario (APS), the drive to meet climate pledges in full sends demand for all the fossil fuels into decline by 2030.

Epstein would have been on far stronger ground had he argued that fossil fuels will remain important for many decades, even as they decline as a proportion of global energy consumption, rather than arguing that it is “virtually impossible” for such a decline to occur. We have a “fossil future” indeed, just not the one predicted and recommended by Epstein.

Given trends in the costs of fossil alternatives, especially renewables, the revival of interest in nuclear energy and the prioritization of energy security in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there is considerable momentum today for greater deployment of fossil alternatives. There is no appetite in OECD countries for expanding fossil fuel consumption, but there is a case to be made in energy poor, resource rich countries for fossil fuels to bridge development until they too seek to decarbonize their economies.

Epstein’s case for fossil fuels requires him to make another forecast — that the projected impacts of climate change on people and ecosystems will be small and manageable. Perhaps he is right, as such modest-impact scenarios can indeed be found in the corpus of work of the climate science community. But so too can scenarios with much greater risks, negative outcomes and large impacts. Reducing or eliminating those risks just adds to the already-strong case for reducing reliance on fossil fuels based on air pollution, energy security and economics. Just like the “catastrophists” that Epstein criticizes throughout, viewing the future through a selective lens of benign scenarios is not consistent with the broader distribution of possible and plausible futures.

Epstein makes a passionate and brave case for fossil fuels. He graciously visited my energy policy class to make this case to my students, who were receptive and appreciative. I applaud him for making the case.

But in the end I am far from convinced. In fact, the fundamental weaknesses in his argument and evidence serve to highlight quite the opposite case — there is every indication that we can and should continue to work to reduce the consumption of fossil fuels and to replace them with viable alternative technologies of energy consumption and production.

In fact, we already are and there is every reason to expect that to continue. Our fossil future is shrinking even as we expect human flourishing to grow.

Please share this post. I welcome comments on the book and its arguments. And I welcome subscribers, at any level. Alex, if you are reading this, I welcome your response, which I am happy to highlight. Thanks all for reading!

Great discussion.

FYI, from 2000 to 2021, 32 countries reduced their overall fossil fuel consumption

While growing their economies

France is one of them

HI All, A great discussion here.

I cannot post images to this comment thread (Grrr)

So I posted up an important on at this Tweet

https://twitter.com/RogerPielkeJr/status/1621529115403894784?s=20&t=XuymkShSGRrXVKJPVbsaUw

Via IEA WEO 2022, it projects that under current policies that global fossil fuel consumption will peak before 2030.

Is such a peak possible? Certainly

Will it happen? Maybe

Is it desirable? Yes

Each of these are different questions, with different implications for evidence and argument.