Technological Chicken and Regulatory Egg

Lessons from the world's successful response to ozone depletion

This essay shares lessons of the world’s successes in responding to ozone depletion, drawn from my work on the science and policy of the U.S. and international response — in collaboration with Michele Betsill (today at the University of Copenhagen) and published 25 years ago. A link to our peer-reviewed research can be found at the bottom of this post. A important side note — I learned a lot about the inside story of U.S. ozone politics in Congress from Radford Byerly (RIP), who was a staff member on the House Science Committee when early legislation was passed in the mid-1970s. He was largely responsible for the language in legislation — specifically the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 — which prompted a default policy stance that compelled regulatory action on ozone depletion under scientific uncertainty. I’ll tell that story in a future post, it is a fun one and crucially important. A lot of policy success depends upon the work of people who work in the trenches where science meets policy, typically lost to history.

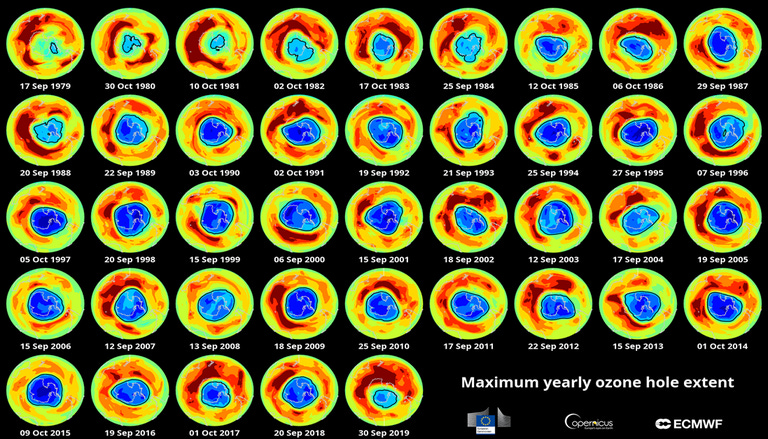

Thirty-five years ago next month, under the United Nations, the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer was introduced for signature by countries around the world. The Convention, and its more widely known Montreal Protocol, represents an effort by nations to coordinate a global response to the challenge of ozone depletion caused by the emissions of industrial chemicals.

Since that time, the Convention has become arguably the most successful international environmental agreement story in history. It may also be the one which historians and policy analysts have argued about the most in an effort to draw lessons relevant to the climate debate.

Conventional wisdom holds that action on ozone depletion followed a linear sequence:

science was made certain —> the science was widely communicated —> then the public demanded action —> these demands motivated domestic and international responses —> the resulting political action led to the invention of technological substitutes for chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) —> followed by wide deployment —> thus successfully addressing the problem

Actually, each step in this chain of conventional wisdom is not well supported by the historical record. Let’s take a look at some lessons that better square with history.

Public opinion not necessarily an important factor driving action

In a poll taken in the United States in December 1987 and January 1988 — the time frame when the US government was considering the ozone treaty — the issue of ozone depletion ranked fourteenth on a list of 28 environmental problems. At the time, fewer than 50% of Americans expressed “serious concern” about the issue, falling behind concerns about farm runoff and contaminated tap water.

Even so, the United States had signed on to the Montreal Protocol several months before and ratified the treaty a few months later. The fact that public opinion on ozone depletion was not particularly intense compared to other environmental issues provides compelling evidence that an important issue does not have to be a top public priority for significant action to occur.

This conclusion is backed up more generally through systematic analyses of public opinion and policy action. For instance, in a review of legislative action in the United States, Paul Burstein looked at enacted legislation for which opinion data were available and found that Congress acted in the direction of public support only in about 50% of the cases, with public opinion having a much stronger influence on Congress when it opposed an action rather than when it supported an action.

More broadly, according to the official UN history of the ozone issue, there were exceedingly few news stories on ozone depletion in the United States, China, the United Kingdom and Soviet Union from 1977 to 1985, when much of the policy framework was developed. The New York Times had about 20 stories in 1982, and in no other year were there that many stories (cumulatively) in 10 different leading newspapers during that period.

In short, significant national and international action on ozone depletion occurred despite (or perhaps even because of) a lack of public conflict or even much awareness of the issue. Hype and politicization were not necessary for effective action.

Scientific uncertainty is never an obstacle to action

In 1974, Mario Molina and Sherwood Rowland published a seminal paper in Nature in which they argued that chlorofluorocarbons posed a threat to Earth’s ozone layer. Ironically, because of their inert properties CFCs were long considered to be a useful industrial chemical for a wide range of applications, including refrigeration. Molina and Rowland’s work suggested that these chemicals were not as inert as previously thought and could pose risks to the atmosphere.

Following the publication of their paper, the US Congress went to work almost immediately, initiating hearings before the end of the year. The White House, under President Gerald Ford, set up the Inadvertent Modification of the Stratosphere (IMOS) Task Force, which concluded that

“fluorocarbon releases to the atmosphere are a legitimate cause for concern”

and recommended that

“the federal regulatory agencies initiate rulemaking procedures for implementing regulations to restrict fluorocarbon use.”

Congress proceeded incrementally, first dealing with “nonessential uses” of CFCs — those for which there were readily available technological substitutes, and putting off until later the more difficult issue of essential uses, those for which no substitutes were available. Regulating “nonessential uses” imposed little or no costs on businesses or consumers, so it was relatively easy to implement. Recall the iron law.

Policymakers had decided that action on the problem of ozone depletion could not wait until scientists reached consensus about the nature of the problem, its causes, and its future impacts. Decisions would have to be made in the face of uncertainties and ignorance – where even uncertainties were unknown.

As Congress made decisions about the chemicals implicated in ozone depletion in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the science of ozone depletion actually became more uncertain, as scientists began to understand the many complexities of the issue. In 1982, the National Academy of Sciences released a report suggesting that the threat of ozone depletion was perhaps less than previously thought, which was seized upon by some in Congress to argue against regulation of CFCs.

Some were skeptical about the magnitude of the ozone threat and sought to capitalize politically on fundamental uncertainties in science. But the policy focus on implementing “no-regrets” policies — which made sense regardless of how scientific uncertainties broke in the future — kept attention away from the details of evolving science and on policy options that made sense despite uncertainties.

This approach contributed to the invention of substitutes for CFCs, making political action all the more easier, as the justifications for action hinged less and less on scientific certainties and more and more on economic opportunities.

Scientific uncertainty is often raised as a reason for inaction or as an obstacle to overcome in the political process. The history of ozone depletion tells that uncertainty need not be an obstacle to effective action. If policy makers needed complete certainty in order to make decisions, very few decisions would ever be made.

Technology enabled political action, and vice versa

In the late 1970s, DuPont was the world’s major producer of CFCs with 25% market share. Its most popular product was called Freon. In 1980, the company patented a process for manufacturing HFC-134a, the leading CFC alternative, after identifying it as a replacement to Freon in 1976.

It is no wonder that DuPont got behind the idea of regulation.

Immediately before and after the signing of the Montreal Protocol, DuPont had applied for more than 20 patents for CFC alternatives. Du Pont saw alternatives as a business opportunity. “There is an opportunity for a billion-pound market out there,” its Freon division head explained in 1988. Du Pont’s decision to back regulation was facilitated by economic opportunity – an opportunity that existed solely because of the need for technological substitutes for CFCs.

Technological advances on CFC alternatives, first developed in the 1970s, helped to facilitate incremental policy action by creating a virtuous circle that began long before the Montreal Protocol and continued long after. Of course, the looming threat of regulation also certainly helped motivate the search for alternatives.

In her excellent book on ozone depletion policy, Ozone Discourses, Karen Litfin explains:

“The issue resembles a chicken-and-egg situation: without regulation there could be no substitutes but, at least in the minds of many, without the promise of substitutes there could be no regulation.”

Viable “technological fixes” can help make it politically much easier for regulations to be put into place — at the same time the threat and reality of regulation can motivate a search for technological fixes. The history of ozone bears out this chicken-and-egg theory of securing progress on difficult environmental issues.

Once a technological fix is available, the politics become much easier.

This essay draws up work published in this paper:

Betsill, M. M., & Pielke, R. A. 1998. Blurring the boundaries: domestic and international ozone politics and lessons for climate change. International Environmental Affairs, 10:147-172.

and is revised from a commentary originally published at China Dialogue.

I welcome your comments and questions. Please do hit the little heart, reStack and share on your favorite social media platform. New subscribers are invited to join the THB community. For those of you who already Subscribe, you are appreciated!

“Viable technological fixes.” DuPont in the wings. The Ozone Solution had means and motive. Politics just slipped in behind the draft.

Setting aside the confusing poli/sci narratives, the fix for climate change is full of faux fixes. Corn ethanol? Lithium batteries? Fickle windmill bird killers? Tempermental ‘Rhode Island-sized’ solar farms? Nukes mostly off limits (except in France). Wall Street and scientists gouging profit.

We know the claimed benefits. What are the real costs? Living in caves as the Climate Saviors pass overhead to their conferences and Caribbean homes? The science (to the extent it is not purchased) sounds reasonable, but the dance is vaguely primitive. We won’t accept the best means (nukes), so we fiddle with vested interests and social-justice contaminated solutions. The motives are suspect in so many places.

Climate consensus is clouded not by the limits of the actual science, but by the poli/scientists posing as priests who receive hoards of cash from partisan contributors and their political sponsors. The media dramatizes every story to raise views and profits. The public smells the truth when they can’t recharge their EV’s or use their A/C due to blackouts. The Law of Unintended Consequences eventually catches up. Save the booming polar bear population so the bears can eat cute baby seals!

I believe that the ozone policy successes you discuss are due, in significant part, to the “Baptists and bootleggers” phenomenon. This term refers to a situation where entities which, one might suppose, would be adversaries instead cooperate. The players here were the big multinational chemical companies which manufactured chlorofluorocarbons on one side, and various Green organizations on the other. It’s obvious why the Greens wanted strict regulation, but why did the chemical companies cooperate? Well, by the time this issue rose to prominence the patents on Freon and various related products had expired and the big multinational chemical companies faced intense cost pressure from smaller companies located in countries with lower cost structures. But if Freon was outlawed other, newer refrigerants would have to be substituted. Guess who already knew how to make those new refrigerants and already had patents.

Thus the Montreal Protocol served the purposes both of the Greens and of industry and was therefore a relatively easy win.