Questionable Climate Scenarios for Central Bankers

Are the climate scenarios used to assess global financial risk of climate change fit for purpose?

The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) might just be the most important global finance institution that most people have never heard of. The NGFS is an organization comprised of the world’s leading central, representing most of the world’s GDP. The NGFS states that its aim is to

help strengthening (sic) the global response required to meet the goals of the Paris agreement and to enhance the role of the financial system to manage risks and to mobilize capital for green and low-carbon investments in the broader context of environmentally sustainable development. To this end, the Network defines and promotes best practices to be implemented within and outside of the Membership of the NGFS and conducts or commissions analytical work on green finance.

Central to achieving this aim the NGFS provides climate scenarios for use by central banks and others to evaluate the risks that they face from climate change and also the risks (and benefits) associated with policy responses to climate change.

Earlier this week the NGFS released its third iteration of its climate scenarios, following version 2.0 released last year and 1.0 in 2020. Because of their significance for policy making in government and the private sector, I’ve tracked the scenarios of the NGFS since the start as part of my continuing research on scenario use in science and policy. One feature of the scenarios that I identified early on was that they were out-of-date — like many scenarios used in climate work. Specifically, very high emissions futures are increasingly viewed to be low likelihood (in the view of the IPCC) or even implausible.

In May, 2021 I had an op-ed in the Financial Times on the use of the outdated scenarios by the European Central bank in its climate stress testing. You can see that below.

In today’s post I highlight one curiosity (of many that I could discuss) associated with the NGFS 3.0 scenarios released this week.

The figure below shows the evolution of cumulative carbon dioxide emissions (from fossil fuels and industry) under the three iterations of the baseline scenarios of the NGFS. The NGFS calls these baselines a “current policy” scenario, which assumes that governments do nothing more than implement climate policies now in place. Also shown are some comparison scenarios — NDCs refers to Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreements, assumed here simply as flat 2020 emissions to 2100, and there are also shown two “net zero” scenarios, one for 2050 and one for 2100.

NGFS deserves some credit in recognizing that our expectations for how much carbon dioxide will be emitted this century have been dramatically revised downwards in just a few years. And the big red arrow in the figure above shows that NGFS has revised its “current policies” baseline down under each new iteration. For those familiar with the RCP8.5 scenario that features in the IPCC and much climate research, its cumulative emissions would be close to 8,000 gigatons carbon dioxide — way off the chart above!

So far so good. But here is where things get curious. The fact that NGFS has decreased the amount of cumulative carbon dioxide emissions by almost 30% in two years would seem to be unquestionably good news — less emissions means less climate change, and thus less impacts and less costs, right?

Well, no. Not according to the NGFS. The figure below shows projected climate damages under the NGFS 2.0 (2021) and 3.0 (2022) current policies baselines. Even as projected emissions have been revised downwards, projected damages have been revised dramatically upwards. That is puzzling.

The top dashed red line shows a change in the baseline and the bottom red line shows a change in the median estimate. The revision is curious because both figures rely on the exact same source, a 2020 paper by Kalkuhl and Wenz. The reliance on that paper is also notable because its damage estimates are themselves based on RCP8.5. It is not at all clear what changes were made to the NGFS application of Kalkuhl and Wenz 2020 that resulted in such a dramatic increase in loss estimates.

One change however is clear. The NGFS went from using a median estimate of losses to an extreme estimate, as they note in their report.

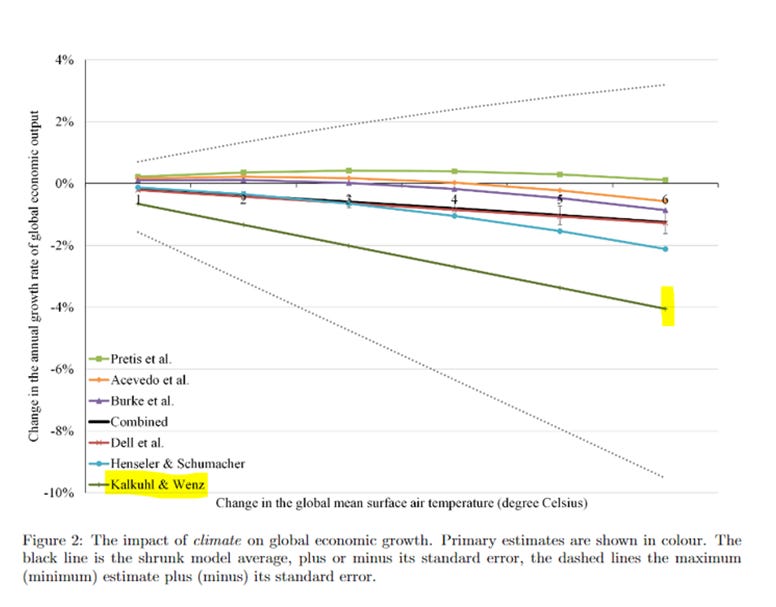

The NGFS 1.0 report in 2020 cited a range of literature on possible future damages from climate change, observing, “There is little agreement across studies about the relationship between temperature and the economy.” By 2021 it had changed course and selected Kalkuhl and Wenz 2020 as the one study to emphasize. According to a new pre-print by Richard Tol that surveys the relevant literature, Kalkuhl and Wenz 2020 provides the most extreme estimate of damage of the set of relevant studies, which you can see in the figure below from Tol’s paper.

So for those scoring at home:

NGFS has dramatically revised downwards projected 21st century carbon dioxide emissions, which should lead to lower projected damages from climate change

At the same time NGFS selected as the basis for its damage estimate the one study with the most extreme results, increasing projected damages

That study relies on the extreme RCP8.5 scenario to generate its damage estimates, increasing projected damages

The NGFS 2022 interpretation of that study resulted in a dramatic increase in damages from its interpretation in 2021

NGFS decided use an extreme result from its analysis (95th percentile) rather than the median, which it has used previously, thus increasing projected damages

The result is that as our view of our collective climate future has become more optimistic, based on more realistic and scientifically grounded scenarios of the future, the picture painted of that future by the NGFS has become increasingly bleak. That bleak future has been constructed by methodological choices that at every turn result in increasing projected damages, completely erasing any impact of the downward revision to projected future emissions.

Projected damages are not the only area where I have methodological questions about the NGFS (e.g., hurricanes!). If the organization were not so globally significant, it would be easy to dismiss their work as not worth understanding or explaining. But NGFS matters a great deal.

However, the analysis above is plenty enough for me to conclude that if I were in finance or government, and being asked to apply these scenarios as the basis for consequential, real-world policy, I’d feel manipulated — almost as if the NGFS is trying to compel certain outcomes rather than provide insight to plausible futures.

Paying subscribers to The Honest Broker receive subscriber-only posts, regular pointers to recommended readings, occasional direct emails with PDFs of my books and paywalled writings and the opportunity to participate in conversations on the site. All paid subscribers get a free copy of my book, Disasters and Climate Change at this link. I am also looking for additional ways to add value to those who see fit to support my work.

There are three paid subscription models:

1. The annual subscription: $80 annually

2. The standard monthly subscription: $8 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

3. Founders club: $500 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who have the ability or interest to support my work at a higher level.

So what do the "Honest Brokers" do about this? An editorial in the WSJ?

Roger, are these analyses peer reviewed or subject to any formal review process?