Earlier this week, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case of Missouri v. Murthy, focused on how far government officials can go in asking social media platforms to take down certain online content posted on their platforms. As Clay Calvert1of the American Enterprise Institute explains, the case addresses the following questions:

How much verbal arm-twisting and jawboning can the government lawfully engage in with social media companies about removing ostensibly false and harmful content before it violates the companies’ First Amendment free speech rights? And did a bevy of federal officials, departments, and agencies unlawfully coerce Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube in 2021 and 2022 to remove conservative-leaning content critical of COVID-19 vaccines, lockdowns, mask mandates, and President Joe Biden?

For many on the political right the correct answers to these two questions are: None and Yes! And for many on the left the correct answers are: Some and No!

Of course, answers to these questions are almost certainly a function of which administration it is engaging in the jawboning of social media platforms. Instead of President Biden and COVID-19, imagine a future Trump Administration asking social media platforms to take down all posts about LQBTQ+ lifestyles, justified as being harmful to children.

Before proceeding, here is my view on the case: While I have serious concerns about government officials who seek to manage narratives and inconvenient experts by influencing what social media platforms publish, I am also aligned with the apparent views expressed by most of the Supreme Court justices in oral arguments — That is, I am very skeptical of the Missouri case.2

Today, I discuss issues that remarkably did not come up in the oral arguments — How should we think about government requests of social media to moderate content that may be uncertain, contested, or characterized by legitimate expert views that are contrary to official government positions?

In the oral arguments, counsel for Missouri, J. Benjamin Aguinaga, was tripped up by a simple hypothetical posed by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson:

Suppose someone started posting about a new teen challenge that involved teens jumping out of windows at increasing elevations. This is the challenge. And kids all over the country start doing this. There's an epidemic, children are seriously injuring or even killing themselves in situations.

Is it your view that the government authorities could not declare those circumstances a public emergency and encourage social media platforms to take down the information that is instigating this problem?

In response, Aguinaga hemmed and hawed, digging himself into a hole that he could not escape from.

Justice Jackson pressed him:

My hypothetical is that there is an emergency, and I guess I'm asking you, in that circumstance, can the government call the platforms and say: This information that you are putting up on your platform is creating a serious public health emergency, we are encouraging you to take it down?

Mr. Aguinaga likely sealed the fate of the case with his response:

I was with you right until that last comment, Your Honor. I think they absolutely can call and say this is a problem, it's going rampant on your platforms, but the moment that the government tries to use its ability as the government and its stature as the government to pressure them to take it down, that is when you're interfering with the third party's speech rights.

Chief Justice Roberts jumped in at that moment, apparently incredulous at the answer and to offer Mr. Aguinaga a chance to reconsider— a chance not taken.

The hypothetical posed by Justice Jackson has some distinctive characteristics. First, there is absolutely no uncertainty — children are jumping out of windows. Second, no one would think that children jumping to death or injury is a good thing, so there would be a near-universal consensus about the undesirability of the children’s actions.

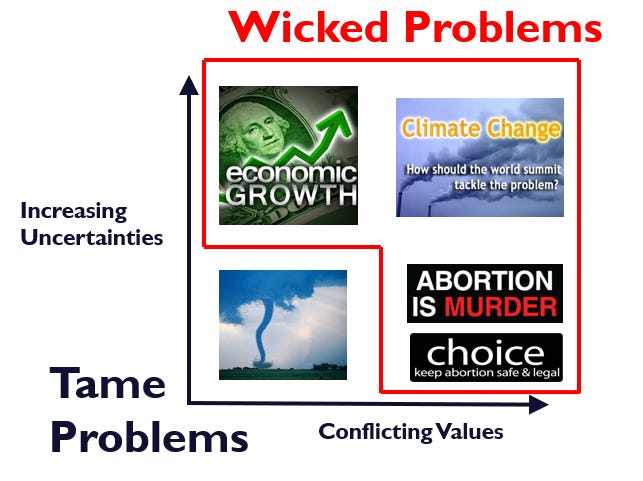

We have a phrase for situations characterized by low uncertainties and little conflict over values — tame problems. This combination of characteristics is only one of four possible combinations, if we array uncertainty x values as a 2 x 2 matrix (below).

Here are some examples of the other three, which are called wicked problems:

Low uncertainty, low conflict: Children jumping out of windows (or, an approaching tornado)

High uncertainty, low conflict: Economic growth

Low uncertainty, high conflict: Abortion politics

High uncertainty, high conflict: Climate change

This simple framework for thinking about how knowledge and values (or science and politics) shape decision contexts was developed by Silvio Funtowicz and Jerry Ravetz decades ago. The latter three cases, where things get complicated, are instances of what they call post-normal science.3

Unfortunately, neither the oral arguments nor the questioning in Missouri v. Murthy entered the territory of post-normal science.

But we can consider the following hypotheticals that might have been raised — Imagine an administration asking social media companies:

. . . to promote an untested treatment for a quickly spreading virus and to remove posts on effective treatments, as some legitimate public health experts preferred by the president think the untested treatment might work, while others believe it will not;

. . . to remove all posts that criticize the president’s performance based on empirical policy analyses, such as on the state of the economy, on the basis that such criticism harms his public standing and ability to govern;

. . . to eliminate all posts from scientists that reference the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, because the administration has an official view of climate science that is contrary to the science of the IPCC.

Most of us will see such actions as problematic, and they are not at all far-fetched as similar real-world examples can be found in other countries. A free speech absolutist might argue that all of these asks are perfectly legal. But of course, there is no absolute right to free speech in all circumstances. For instance, the Supreme Court ruled in 1969 that the government may limit speech that is “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action,” and is “likely to incite or produce such action.”

Of course, problematic actions by the government to limit speech are not the same as actions that are illegal or unconstitutional. The importance of clarifying this distinction is one reason why it is unfortunate that oral arguments in Missouri v. Murthy did not engage post-normal science.

The crux of the issue can be found in several amicus curie briefs filed in support of Murthy. One, by a bipartisan group of election officials, argues (emphasis added):

Election officials and the government agencies that support the administration and integrity of elections are repositories of accurate, critically important information about elections in the United States. . . Social media platforms rely on communicating with election officials to supply accurate information for the platforms’ voluntary public education efforts, to correct false and misleading content, and to identify threatening content that violates the platforms’ moderation policies.

A second, by Senator Mark Warner (D-VA), argues (emphasis added):

Foreign malign influence campaigns seek to destabilize American society . . . The best way to combat foreign malign influence is cooperation between the public and private sectors. Threat sharing allows the government and social media companies to combine disparate data sets and share appropriate information.

Few would object to the importance of disseminating accurate information or countering malign influence campaigns — these involve tame problems. Of course, things get wicked quickly when accuracy and/or malignancy become contested — debates over policy responses to COVID-19 provides an obvious example.

Things can get even more complicated: What if government officials ask social media companies to promote inaccurate information? Or if government officials are the malign influencers? What then?

It is tempting to think that if only we had some way to unambiguously identify what is true and what is untrue then we could at least take the issue of accurate information off the table. It is this instinct of course that has contributed to the rise of self-appointed fact checkers and efforts to police misinformation.

Without going into the arguments today (but they will come), the idea that some heroic individuals have special access to ultimate truths that can be used to draw a bright line between the accurate and the inaccurate is a holy grail. Of course, along with claims that one can divine truth is often the linked belief that one’s political allies have such special access to truth, and that political opponents traffic in untruths.

Contested knowledge and values are of course why politics is important and necessary. As Walter Lippmann once explained, the goal of politics is not to get everyone to think alike, but to get people who think differently to act alike. Lippmann explained more than a century ago,4 long before the concept of post-normal science was coined, that there may be a simple and obvious explanation for conflicts over what is right or wrong, true or untrue:

And since my moral system rests on my accepted version of the facts, he who denies either my moral judgments or my version of the facts, is to me perverse, alien, dangerous. How shall I account for him? The opponent has always to be explained, and the last explanation that we ever look for is that he sees a different set of facts.

So where does this leave us? I’ll suggest eight tentative conclusions for today.

Missouri v. Murthy is not the right vehicle for addressing situations where government officials may seek to manage information by making asks of social media platforms. I side with Murthy. That is not the end of the story, however.

The legal concepts of persuasion vs. coercion by governmental officials in shaping speech remain fundamental and deserve greater explication, but it is somewhat tangential to issues of governance in situations of post-normal science.

There are many situations where it is perfectly appropriate for government officials to make asks of social media companies about the moderation of their content — Children jumping out of windows based on a social media “game” is an obvious example.

There are also many situations where it would be absolutely improper for government officials to make such asks of social media companies — For instance, an ask to remove all content of scientists who promote the findings of the IPCC.

Both democracy and expertise are better served when such asks are made from the “bully pulpit” before the public, rather than behind the scenes. However, there are situations (e.g., national security) where that is not the case.

I doubt there is any possible legal or judicial solution to the challenges of squaring First Amendment free speech rights with the importance of dissent and challenge, as well as the right to express views at odds with an administration’s official position, contrary to an accepted scientific consensus, or views that are completely false.5 In other words, there are no bright lines here, but many shades of grey.

Stronger norms would help. Specifically, would it be possible to reach a consensus the idea that government collaboration with social media platforms is largely unproblematic in the context of tame problems but increasing problematic in the context of the wicked problems of post-normal science?

We in the expert community must do a better job recognizing the importance of governance under conditions of post-normal science and act accordingly. Too often we seek to turn such situations to our own political advantage by claiming self-servingly that we, and we alone, can identify misinformation and help to eradicate it from the political arena.

The questions raised by Missouri v. Murthy go far beyond the First Amendment. They raise issues of how we can collectively govern a diverse nation that depends mightily on expertise and the knowledge generated by that expertise, while simultaneously accepting that experts have a diversity of legitimate views, including political views. At the same time, citizens (and some experts) often express views that are just plain wrong, and in most cases, they have every right to do so. I see how we seek to resolve these issues as fundamental to the future of American democracy.

Can we pass Lippmann’s test of the goal of politics, and agree that we need not all think alike, but instead, figure out how to act alike?

❤️Click the heart if you think we can pass Lippmann’s test

Thanks for reading! I welcome your comments, critique, alternative points of views. If I judge them wrong I’ll remove them — Just kidding! Please expect to see more posts of this type, focused on the themes of my book in progress, Uncomfortable Knowledge. That means I very much appreciate your stress testing of my arguments, challenging them, and helping me to make them better. Remember, THB is a group effort and it is also reader supported. I value your support at whatever level makes sense for you!

Not that I know anything, but I expect a 7-2 ruling in favor of Murthy, with Justices Alito and Thomas dissenting. Justice Gorsuch may join the dissent, but I’d guess not.

My book, The Honest Broker, after which this site is named, provides an extended excursion into the landscape of post-normal science. I am currently working on a sequel, provisionally titled Uncomfortable Knowledge, Saving Science and Politics from Ourselves.

It is indeed a wicked problem.

Rather ridiculous making up some fable extreme scenario of when government censorship is justified and pretending that is relevant. When the reality is the exact opposite. Extreme scenarios of obscene and obviously & deadly instances of government censorship:

1) A laptop is found which contains MAJOR damaging & truthful information about a presidential candidates nefarious & highly illegal and national security threatening corruption, so the most powerful law enforcement & intelligence apparatus on Earth goes into overdrive to suppress that information right before a critical presidential election

2) There is major serious and accurate scientific information discovered that presents strong evidence that a gene therapy product being pushed on the public through extraordinary government sanction may pose major health dangers while its effectiveness is dubious to say the least. And that information is suppressed by extreme government intervention to blockade free speech & force publication of false information presented as factually correct.

These 2 events did happen, they're not wild fantasy fables. And I took those 2 right off the top of my head, undoubtedly the reader can find dozens of other similar events that have happened, not fantasies, not fables.

These supreme court justices sound to me like they are divorced from the real world that people actually do live in.

Recall that one of the damaged parties in the Missouri vs Murthy case was Jay Bhattacharya, a distinguished epidemiologist from Stanford with 30 years' experience studying epidemics. He was silenced because his views in the Great Barrington Declaration, to protect the most vulnerable while liberating children and young adults at low risk, clashed with those of the CDC.

Bhattacharya endorsed the approach taken by Sweden, which, according to a recent study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suffered only 3.5% excess deaths in the COVID years 2020-2023, compared to 12.7% in the US in that same time period. So to avoid embarrassment, government apparatchiks silenced a highly competent experienced professional whose ideas, if adopted, would have been hugely beneficial to the nation.

Consider, Roger, if government bureaucrats are allowed to pressure social media companies to silence and cancel voices which disagree in some nuance with their preferred policy options. There are plenty of such bureaucrats who think anyone who differs from the dogma of Al Gore, Bradley, Mann and Joe Romm should be squelched. That would mean you and Judith Curry would be canceled, silenced, deplatformed, I would greatly regret that.